In 2015, agents for the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol seized $1.4 billion worth of fake Louis Vuitton purses, iPhones, Lebron James jerseys and more. The number of counterfeit furniture pieces, like Eames Lounges, Saarinen Tables or Emeco Navy Chairs? A big, fat zero.

“If you’re an armed U.S. Customs agent and you’re trying to save America from drugs coming through, you wouldn’t normally be worried about couches, right? That’s our job to make that important,” says John Edelman, the president of Be Original Americas (BOA), a non-profit that battles the fake furniture market.

Since 2016, Be Original has trained thousands of Customs agents at more than 300 ports in the art of spotting fake furniture. The current yield: upward of $15 million per year in seized furniture from some of the most respected names in the business — Herman Miller, Emeco, Knoll and more.

Edelman, who joined BOA after the program had already begun, says the key ingredient to stopping fakes was making the value of original design known the very Customs agents intercepting them — in both dollar values and creative rights terms.

“They weren’t getting credit if they seized a container of counterfeit furniture like they were if they seized a container full of heroin or something like that. We helped them start to legitimize the dollar value of these designs,” Edelman says.

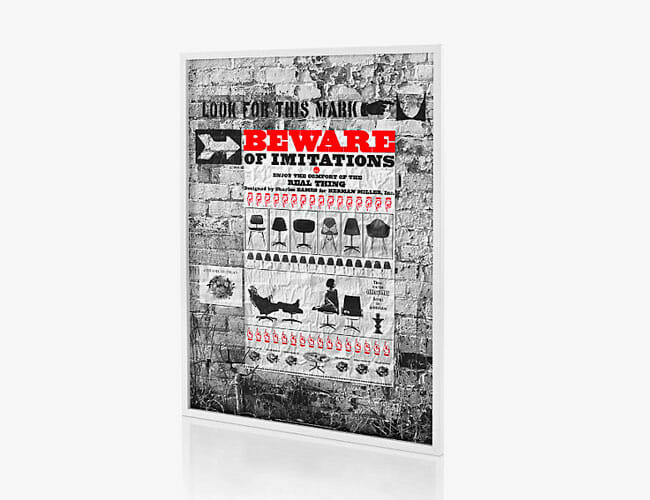

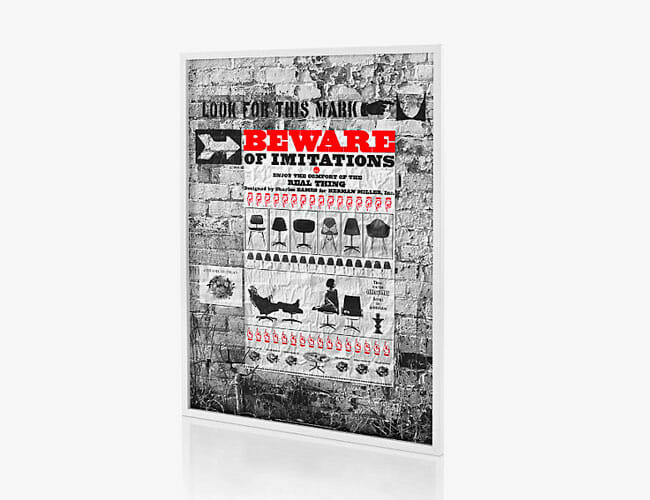

Herman Miller’s infamous “Beware of Imitations” ad appeared on the back of Art & Architechture in 1962 in response to a wave of fake Eames products flowing into th U.S. You can buy a poster version of the ad today through the brand’s website.

BOA began by dispatching representatives and envoys from member companies to train agents in the art of fake-spotting. Frequently knocked-off companies like Emeco and Herman Miller — whose Eames Lounge and Ottoman may be the most counterfeited piece of furniture in the world — joined the fight. Edelman says they trained agents on country of origin first, and later added on higher level details. “If you know this chair is made in France and it’s coming from a Chinese shipping container, it’s probably not real. And if you know where the logos go on the product and details about the design of the original, you can take it a step further,” he says.

Gregg Buchbinder, CEO of Emeco, estimates that around 2,300 of his company’s prolifically ripped-off chairs and stools were seized by Customs agents last year. In financial terms, it comes out to roughly $1,400,000 in chairs and stools — yet he says the lost revenue is only part of the problem of fake furniture.

According to Be Original Americas, Emeco’s 1006 Navy Chair is one of the most frequently seized designs. The easiest way to spot a fake? Most fakes have four bars down the back — the original only as three.

“[Knock-offs] are lower cost products with shorter lives. This means more waste in landfills and oceans,” Buchinder says. “It’s a race to the bottom, which means Emeco would have to cut corners to get there — no heat treating, no hand brushed finishing, no anodizing. The chairs are made to look identical, but with these steps missing, welds will crack, legs will bend and life [of the product] is reduced.”

The problems of cheap fakes from overseas are doubled by problems at home — major retailers are copying Emeco’s work, too. First it took Restoration Hardware to task for its “Naval” chair recreation of Emeco’s Navy chair and later Ikea for copying its stackable 20-06 chair. Emeco won both suits, but, as Buchbinder notes in Quartz, litigation is the last place he wants to spend company dollars.

“When sales are impacted by knock-offs, income to designers is reduced, and interest or ability to continue designing new innovative products may decrease. Hopefully [design consumers] will learn design is much more than style,” he says.

In the grand scheme of things, Buchbinder, Edelman and BOA can’t be certain how much effect they’re having — there’s not a lot of data surrounding the fake furniture industry, and the fight at the borders is only three years old. But, according to Buchbinder, every shipping container seized at a port means less his company has to lean on a costly litigation process.

“I have not seen any counterfeiters who have gotten busted try to do it again,” he says.