Mechanical watches, though beautiful, are ultimately just things — when you lose one or one is stolen, or it breaks, nine times out of ten, you move on with your life, regretting the situation, but none the worse for wear. You can always replace a thing, and most of the time, there’s no particular special, life-changing significance to an object.

But sometimes, the situation is distinctly different. Once in a very long while, an object is imbued with a history that is simply so significant, it’s nearly incomprehensible to the average person. The Patek Philippe reference 1461 owned by Lieutenant Charles Woehrle is one of those objects.

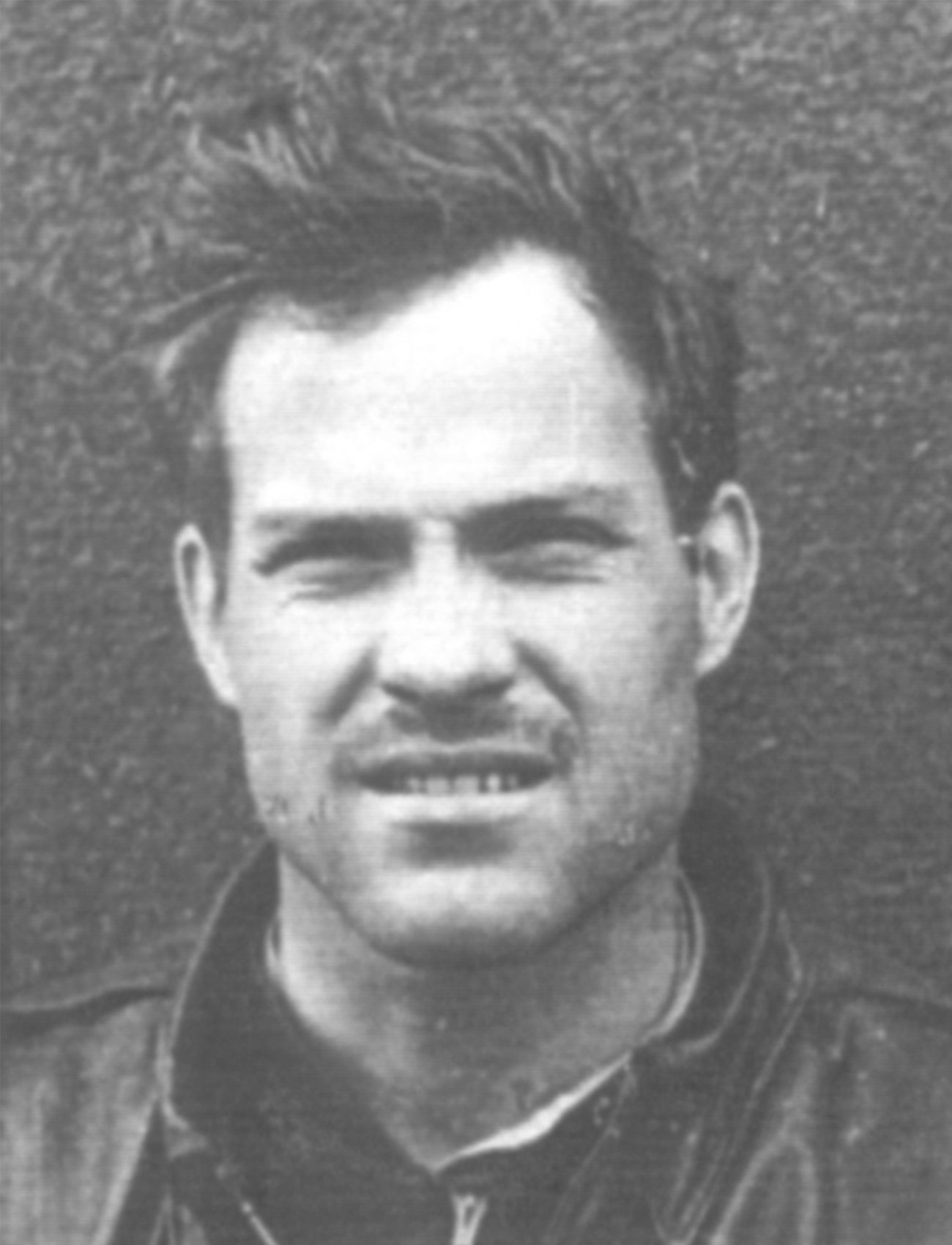

Lt. Woehrle was an officer in the Eighth Air Force during World War II, a bombardier on a B-17 flying missions over Nazi-occupied Europe. On May 29th, 1943, his Flying Fortress was hit and he was forced to parachute from the aircraft. Though he survived the fall into the sea, he was soon captured by the Germans and interned at Stalag Luft III, the camp that inspired the 1963 Steve McQueen film “The Great Escape.”

Conditions were difficult and Woehrle barely survived the harrowing winters without enough food and warm clothing. One day, in March of 1944, the young lieutenant came upon a piece of promotional literature for wristwatches that had found its way into the camp. Woerhle looked through the brochure, and, recognizing the name Patek Philippe, was intrigued. He decided to write to the company, explaining that he was an American POW, and though he couldn’t pay for a watch, he wrote that if Patek could send one to the camp that they thought he could afford, he would pay for it immediately upon his release at the end of the war.

Many months went by and Woehrle forgot about the entire thing, until one day, his commanding officer came to see him. The man explained to Woehrle that a package had arrived from Geneva, and the commandant of the camp was reticent to release it, fearing that Woehrle would use it to bribe a guard. The senior officer assured the commandant upon his own word that Woehrle wouldn’t do such a thing, and the commandant handed over the package.

“And so the next day I opened the package, and there was this perfectly beautiful wristwatch on a black alligator strap,” explained Woerhle. “The news ran all through the camp. There was a line of men all up and down the hall outside of my room. They all had to see the watch. What an event it was for us! Such a thing arriving at that camp from the finest watchmaker in the world, addressed to a POW…it was hard to comprehend.”

Indeed, having such a beautiful object from the outside world arrive to a camp in which the men were barely surviving, living in filthy conditions and terribly, terribly homesick, was an incredible boost to morale — and not just for Woehrle, but for all the men. It was a simple, time-only reference 1461 Calatrava-type watch in steel, one of a series made between 1940 and 1953, and Woehrle cherished it.

Not long afterward, the men were force-marched from Stulag Luft III to another camp, enduring 70-plus miles of terrible marching in the freezing cold. On April 29, 1945, Patton finally arrived and liberated the men, ending Woehrle’s terrible, 22-month long ordeal. Unfortunately, several decades later, Woerhle’s house was robbed, and his prized Patek Philippe was stolen. Several years ago, his niece, Louise, a documentary filmmaker, asked her uncle if he had ever had a watch during his days as a POW.

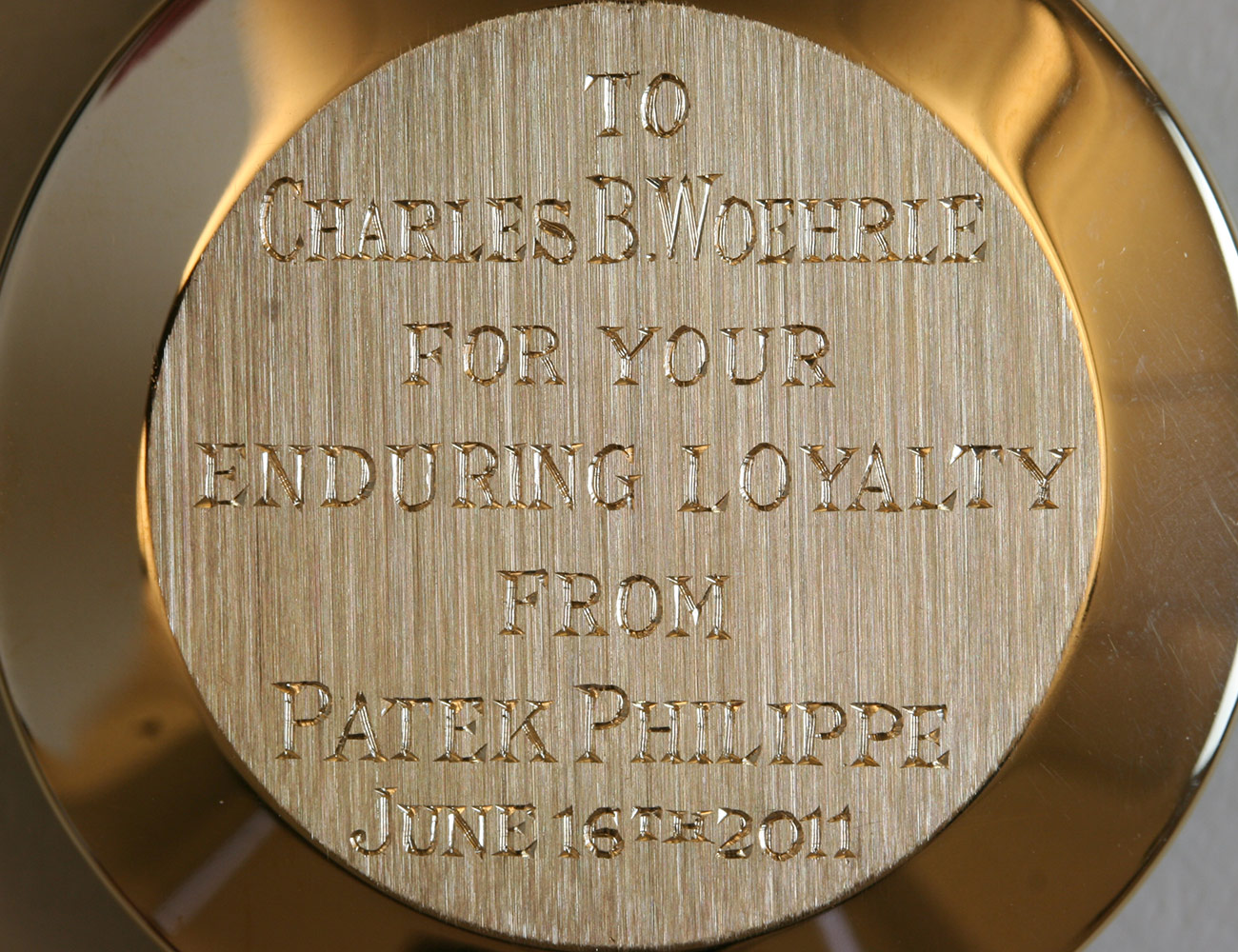

“Let me tell you a story about a watch,” he said, and recounted the entire chain of events. Moved, Louise decided to try and see if she could trace the serial number of the watch, perhaps leading her to its current owner. She reached out to Larry Petenneli, President of Patek Philippe US who, after hearing the story, was eager to lend a hand. Realizing that someone might have purchased Woehrle’s 1461 from the thief not realizing it was stolen and have had the watch for several decades already, the two decided not to pursue tracking it down. Instead, Mr. Petenneli checked with his colleagues and with Mr. Thierry Stern himself, President of Patek Philippe, who agreed to gift a similar watch in yellow gold to Woehrle.

Louise, who had been facilitating this entire process with Patek Philippe, was so moved by the company’s willingness to replace the watch for him, that she made sure to include the story in her documentary about her uncle, called Stalag Luft III. Last week, a private screening of the documentary was held at Patek Philippe US’s headquarters in NYC, a film in which Woehrle described the entire story of his captivity and, of course, the story of his special Patek Philippe.

Lt. Charles Woehrle passed away on Marhch 25th, 2015, two years shy of his 100th birthday — his legacy of heroism, however, and the story of the Greatest Generation, lives on.

For more information on the documentary, including updates regarding festival showings of, check out Whirlygig Productions