The 90’s brought a lot of good, bad, and forgettables — Sony Playstations, Google, reams of flannel, and an earworm from Chumbawamba. But it was also a watershed of innovation in mountain biking. Oddly, we are just now seeing some of these innovations spill off the dirt and on to the road, which had us asking, after 20 years, why is it that Roseanne is back on ABC, but we are only now just starting to see some of cycling’s most innovative trends embraced by road cycling? Has road cycling innovation hit a dead end?

But let’s backpedal a bit, and follow the technology, because the answer to that question may lay in a burgeoning new sport.

“In the 1970’s, I would go to the local dump scavenging for old paperboy bikes, braze up the broken parts and fix them up for exploring Mount Tam,” said Steve Potts. Potts has been making exquisite titanium frames and components for almost 40 years. His roots tunnel deep in the Marin County mountain bike scene, the cradle of mountain biking. “Rims and spokes were heavy, the components were marginal for the type of riding we were doing,” said Potts. “We made our first bikes out of a mishmash of parts that were available.” Potts and his friends soon started building their own components for their “ballooner” bikes. The band of eccentric, DIYers started building their own hubs, headsets, brakes and bearings. The sport was young and direction was malleable. The magic they spun in that garage injected a vital dose of innovation that sparked an entirely new sport. That backyard garage? Yeah, that became Wilderness Trail Bikes, who at the time, owned more cycling IP than anyone else in the two-wheel world and today makes some of the finest mountain bike parts and accessories available on the market.

Fat tires, stout bottom brackets, and knobby tires; Mountain bike 1-dot-0 grew slowly around a clunky steel frame until 1990, when Rockshox and Manitou each debuted a fork that looked like it was stolen off a motocross bike and jammed up the head tube of a rigid frame. “From a technology standpoint, suspension reinvented how people look at bikes in both design and the ride,” shared Eric Schutt, marketing manager at Hayes Performance Systems. Floating over bumps and bombing rock gardens, suspension elevated the average ‘hold my beer’ rider to full-blown superhero status.

The introduction of suspension travel touched nearly every part of the bike, and a flood of innovations shortly followed. And then, in 1997, when bike disc brakes hit the scene, the sport was born yet again.

Rim brakes function by pinching brake pads on a wide rim, which essentially boils down to a lot of squeezing, collecting mud, and suspicious stopping power. On a good day, you could burn through a pair of brake pads in a single ride. Mountain bikers were won over by disc brakes’ superior ability to grip in wet and grimy conditions, but also because disc brakes allowed riders to carry their speed through turns much more efficiently than rim brakes ever could.

Discs still had their faults though. They were heavy, and the monster grip of the disc brakes caused a high rotational torque on suspension forks that were destroying quick release skewers. The grip was so strong, that it could yank a quick release out of a vertical dropout. Thru-axle systems evolved to solve both dilemmas, stiffening the forks while locking the wheels in place. A commitment to disc brakes implied adopting thru-axle systems.

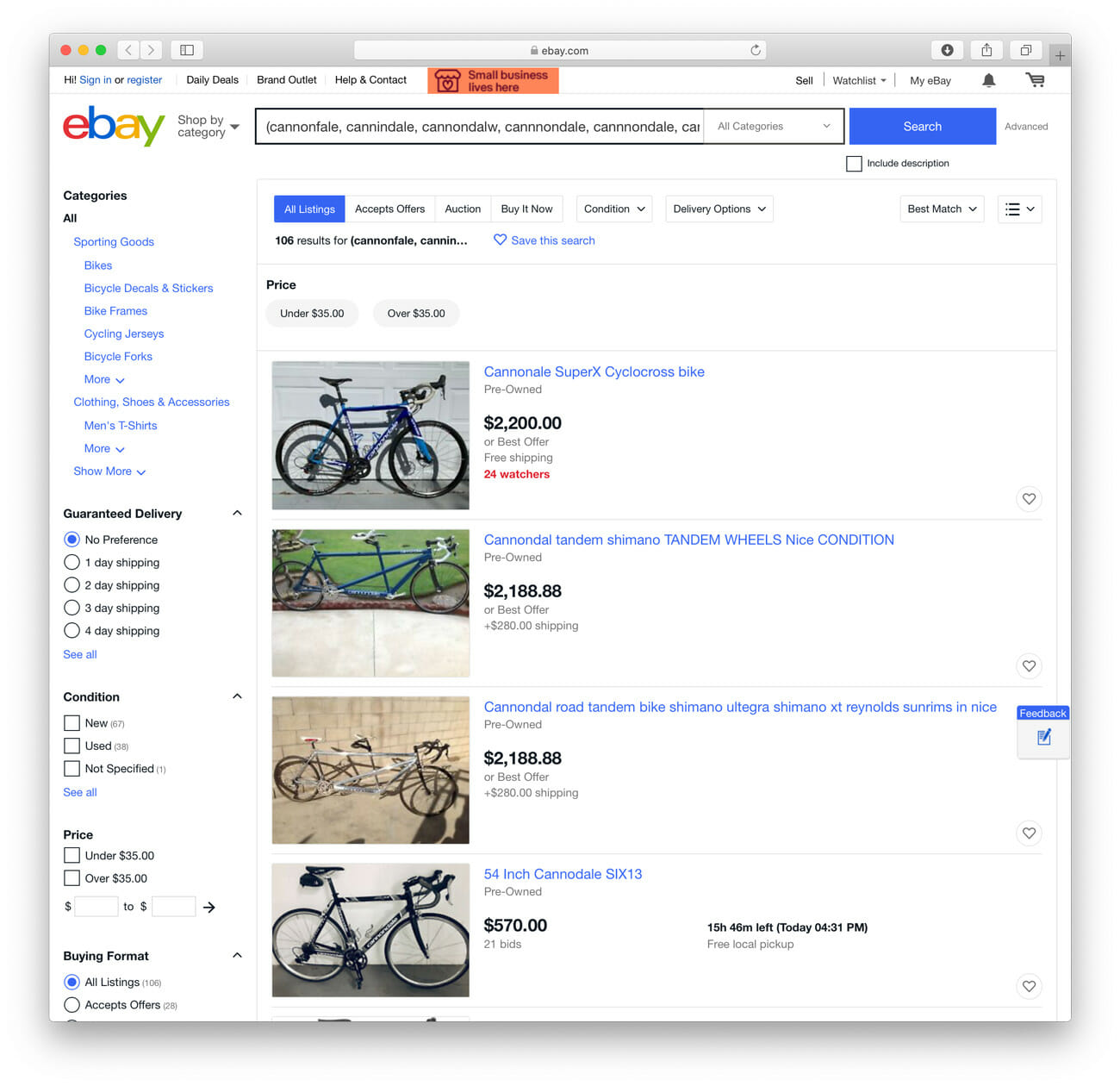

The Specialized Tarmac disc takes all that mountain riders loved about discs and brings it to the road.

If suspension was a game changer in mountain biking, disc brakes were the gateway drug for road cycling to (reluctantly) accept mountain bike trends. Moving the brakes off of the rim allowed suppliers to use lighter materials (read carbon), shaving ounces (read seconds) off of wheelsets. Hence rims were no longer forced to be squeezed between the brake calipers and could relax from 23mm to 25mm, 28mm, 32mm or more. Wider tires put more air between the rider and the road while yielding a smaller footprint. In other words, disc brakes allowed extra tire girth that is both more comfortable and faster on the road.

Walk into any bike shop today and you’ll be hard-pressed to find a worthwhile mountain bike that features rim brakes. “Road bikes aren’t far behind,” shared Michael Zellmann, Senior Public Relations Manager at SRAM, the first to bring disc brakes to the road five years ago. “Sales of road disc brakes grew from 40% to over 60% from 2017 to 2018 and are expected to grow even more in the future.” Truth to word, Specialized announced that it will no longer be selling rim brakes on stock bikes in 2018. The disc brake and thru-axle movement appears to be here to stay on the road.

But disc brakes on road bikes aren’t the only innovation the aerodynamic-focused road bike designers are nicking from their fat-tire counterparts. Italian component manufacturer Campagnolo recently released a 12-speed cassette designed specifically for road bike applications. 12-speed cassettes became popular in the mountain bike industry with the launch of SRAM’s Eagle 1×12 groupset in March of 2016. While it’s too early to tell if the technology will be adopted in the way that road disc has, it’s another clear example of mountain bike designers setting the trend.

Why hasn’t road cycling seized on innovation in its own world? It’s hard to ignore that on the road, tradition is king, and that the UCI (or Union Cycliste International, professional road cycling’s governing body) has played more than a small part in stifling innovation. “It’s a conservative market” Zellmann continued, “you can’t simply retrofit your old bikes with new technology. Big innovation often requires taking the plunge to buy a brand-new bike and master new skills.”

It’s also important to remember mountain biking grew out of its own creative crucible; the sport had a blank canvas to paint and they defined their own future. And then there was Floyd, the Festina affair — followed by Lance — the late 90s and early aughts stripped some of the slickness off of road cycling.

The Open UP is blurring the lines between mountain and road bikes.

10 years later, the Tour still reigns king, but road riding has been reinvented by the people through the growing popularity of cyclocross, gravel and adventure riding. While the traditional road ride would be quarantined to the pavement, nowadays a typical road ride may start out on tarmac but toss a patch of dirt or gravel under the rubber before sewing it up back on the road.

Leading this new trend are designers like Gerard Vroomen, director at 3T and Open, who has seized on the opportunity to develop new bikes that allow riders to swap out a range of wheelsets – from 25mm road all the way up to 2.1″ mountain bike tires. Vroomen has also taken the 1x (pronounced “one by”) drivetrain and ported it over from the mountain bike and cyclocross world to somewhere many would think it doesn’t apply: pro tour aero road bikes. The Vroomen-designed 3T Strada is currently being ridden in the pro tour by the Aqua Blue Sport team and features not only soon-to-be-standard road disc brakes, but also a Sram Force 1×11 derailleur on a very aerodynamic road bike frame.

But before you label road bike designers as the only ones looking across the aisle, mountain bike design is worth a closer look as well. “The flow of technology isn’t all one directional,” said Zellmann. “Electronic shifting and power meters are being adopted by the mountain bike scene.” New staples in the road world are slowly backwashing into the muddy waters of mountain biking.

Which just goes to show that an abundance of technology benefits everybody and creates new opportunities for people to fall in love with cycling all over again.