I

t’s 1:20 a.m. It’s cold and near pitch black. I’m somewhere around 10,200 feet above sea level, traversing the snowfield above the Cowlitz Glacier on the southeast flank of Washington’s Mount Rainier. Behind me, headlamps begin to ignite; their lights flicker in the distance as other climbing teams back at Camp Muir make preparations for the summit. In front of me, the rope locked into the carabiner at the front of my harness slides across the glittering snowpack. A crevasse looms, no more than a foot across. As I step over, I steal a downward glance — it’s dark and seemingly bottomless in the beam of my headlamp — before the gentle pull of the rope urges me to keep moving.

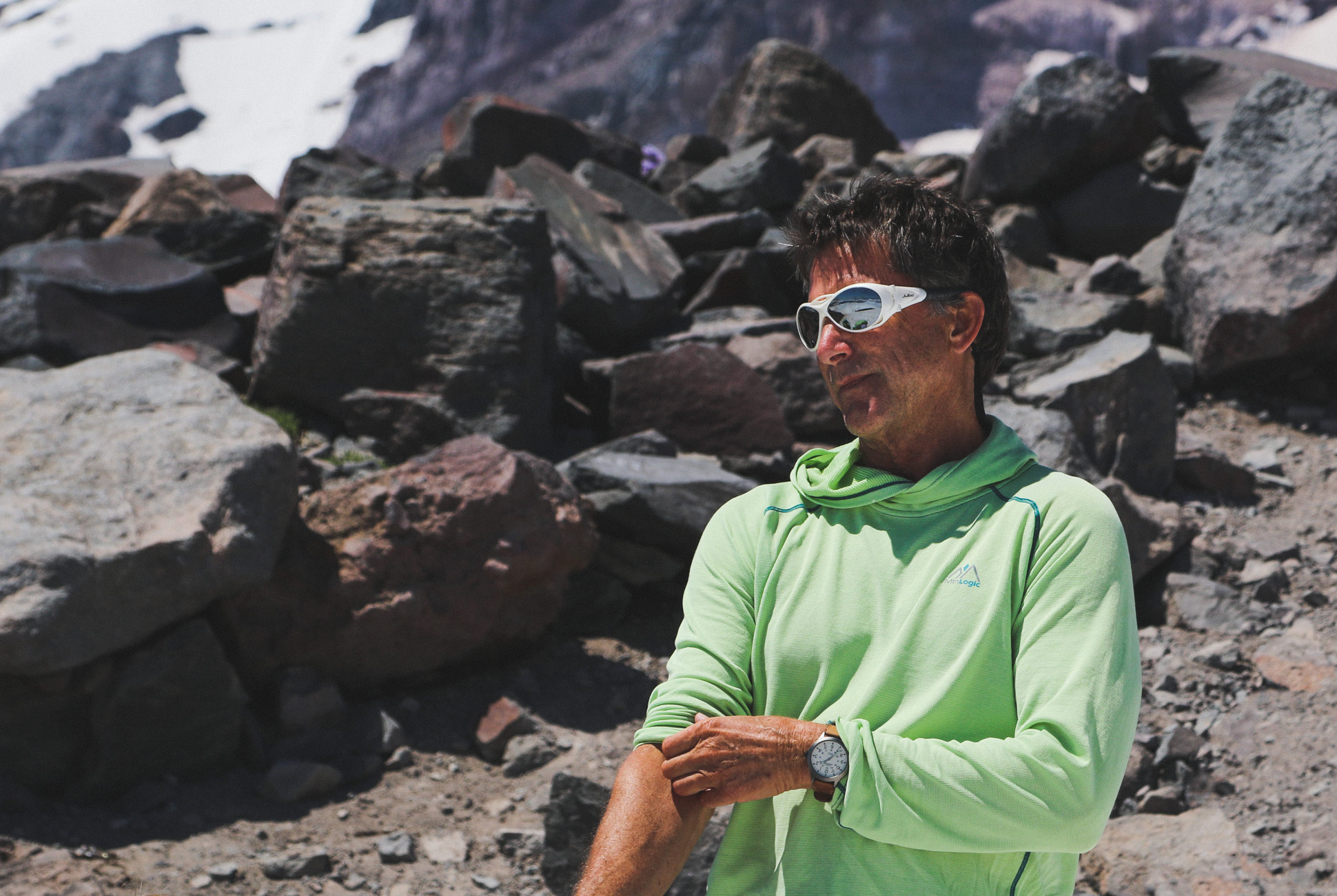

At the lead end of that rope, silhouetted in the yellowish glow of his own headlamp is my guide, Peter Whittaker. He’s the one setting the pace of our slow assault on the mountain, silently compelling me upward with the steady pull of the rope. Whittaker has climbed this mountain before — 249 times, to be exact. He’s set foot on the tallest summits around the world and has accrued quite the climbing résumé: two expeditions to Denali, 14 to Kilimanjaro, three to Antarctica’s Mt. Vinson, eight to Aconcagua — and the list goes on. But Whittaker is anything but the prototypical grizzled old climber, filled with stoic resentment for how the sport has evolved. He emanates youth with a humor that belies his age. Climbing, to him, is and always will be one thing: fun.

Mountain climbing wasn’t much of a choice for Whittaker. He was born into it; it’s in his blood. His father, Lou Whittaker, was part of the first American team to summit Kanchenjunga, nearly lost his toes on K2 and led the first American ascent of Everest’s North Col. Jim Whittaker, or Uncle Jim, as he’s known to Whittaker, was the first American ever to reach the summit of Everest on May 1st, 1963. Growing up, it was expected that one generation would follow in the footsteps of the previous — he was constantly badgered about climbing Everest. “That bothered me a lot; everybody asked me that,” he says. “It was never really a huge goal for me.” Nevertheless, the allure of the mountain took him — Whittaker has attempted Everest four times and reached the summit once, in 2009.

Peter Whittaker attempted to climb Everest for the first time in 1984.

At age 25, he would’ve been the youngest American to reach the summit.

But it was in Washington, on Mount Rainier, where every climber in the Whittaker family earned their legs. Whittaker’s father brought him to the top of Rainier’s volcanic peak for his first big climb at age 12. “I cried. I hated it! It was really cold; I think I was wearing jeans that got wet and then froze,” says Whittaker. “It’s crazy that I continued doing it, because it really wasn’t a great experience.” Four years later, at age 16, Whittaker became a mountain guide on Rainier, and in 1998 he took over the reigns of Rainier Mountaineering Inc., the guide service his father established in Ashford, Washington in 1969. “Apparently there was something there. A lot of therapy,” he jokes. Now, guiding clients to Rainier’s Columbia Crest has taken a backseat to managing his various businesses, but he makes sure to get in a few climbs every year. This particular climb is the first of the season for Whittaker, and his 250th Rainier summit overall — the same tally held by his father.

For me, this climb is also a first. My first up Rainier, but also my first serious mountaineering attempt of a peak of this caliber. I’ve been to higher elevations in Ecuador and Bolivia, but on mountains that weren’t glaciated (read: no ropes or harnesses, no icefall or bottomless crevasses). When I arrived at Base Camp, I had little idea of what to expect. We spent that first afternoon dialing in our gear and going over our planned route up the mountain. The following morning we set out to Rainier’s lower snowfields to practice using an ice ax, walking with crampons, rope technique, and falling — or more specifically, stopping ourselves after falling. There are half a million ways to fall on a mountain; we practiced three.

On day three, we began our ascent. The slog up to Camp Muir begins in Paradise (5,400 feet) with a mix of paved and gravel paths that carry tourists to the meadows and basins of the lower mountain, where they can view lupines and spot marmots. Climbers mingle with the crowd; it’s easy to tell one from the other based on the size of the pack and the amount of rubber in one’s boot sole. We clunked up these paths through a thick mist until asphalt and gravel turned into snow.

Somewhere between eight and nine thousand feet the clouds morphed and thinned, revealing the full expanse of Rainier for the first time. We were gaining on the glaciers, some now parallel to us and not too far in the distance. I took my last step off the Muir Snowfield to arrive at Camp Muir around 4 p.m. At 10,188 feet, Camp Muir is a small group of stone and wood structures occupying a precariously terraced ridge. It’s home to a ranger station, a public hut, guide service huts and two toilets. The guide shelter, built in 1916, is the oldest stone structure in the park. There was still plenty of daylight when we reached the camp, most of which would have to be used for sleep. We’d be waking up at midnight to set out for the summit.

At Camp Muir I dialed in my kit for the day ahead; it was quiet up on the mountain, and it seemed a shame to spend such a beautiful afternoon sleeping in a dark bunk. I ate a bag of dehydrated beef stroganoff while looking out over the Cowlitz and Nisqually glaciers; my back to the slopes I would need to ascend to reach the summit. Whittaker shared some funny old climbing stories that I won’t repeat here — they’re more suitable for the mountain.

In 2015, more than 10,000 climbers attempted to summit Mt. Rainier.

Less than half made it to the top.

W

hittaker never went to college. After graduating from high school, he moved to Utah to join the ski patrol at Snowbird and later became a helicopter ski guide at the mountain. Summers were spent climbing and guiding — he was the prototypical mountain bum. Nevertheless, Whittaker has started more businesses than he can count. Ashford, RMI’s home base, covers only slightly more than two square miles, and yet it’s dotted with them. In addition to the guide service, there’s a gear rental shop, the Base Camp Grill, Whittaker Mountaineering, Base Camp Cottages and a converted garage that now houses Whittaker’s latest venture, MtnLogic.

Whittaker’s first venture, Summits Adventure Travel, was established after a failed attempt at Everest in 1984. The idea was to leverage the loyal clients he had already worked with an international expedition company. “I printed a brochure with like seven trips and I had only been on two of them,” he says. “Suddenly someone gave me $5,000 to go to Kilimanjaro and then there were seven of them and I had $35,000 going, ‘Ok, I gotta make this all work now.’” It did. Whittaker traveled and climbed the world over with wealthy clients for 14 years, picking up an unofficial MBA in the process. “My higher education came from being 16 years old, tied to successful adults,” he says.

Business and climbing are by no means mutually exclusive. A survey of climbers active during the latter half of the 19th century, a period that’s been dubbed “the golden age of alpinism,” reveals no shortage of European aristocracy. In fact, the two align so closely it’s no wonder that denizens of the corporate world today are so attracted by Everest and the rest of the Seven Summits. Terms like inventory, assessment, financing and, most importantly, risk management are interchangeable on and off the mountain, where the primary objective and marker of success is a tangible goal, measured either in dollars and cents or feet and meters.

Perhaps that’s why Whittaker has seen success in both realms. At its height, Summits Adventure Travel was grossing roughly $750,000 a year with a 25-trip itinerary. Whittaker knowingly describes the act of guiding as the perfect joint venture. “A client hires me for my decision-making ability, my experience, my knowledge, strength maybe, and conditioning — I represent the assets. They pay me for those assets and they actually represent the liabilities — they don’t have the experience.” Whittaker, like all mountain guides, makes a binding agreement as soon as he ropes up with a less-experienced client and assumes that risk with their lives. And that might be the line in the sand between mountaineering and business; a rough day at the office might mean project delays or dollars lost, whereas, in Whittaker’s own words, “a bad day in mountain climbing, people die.”

“I would define myself as a good climber, but really as a better guide,”

says Whittaker.

B

ack in the dark, our team trudges onward, upward. I try to identify the main geological features that mark our route, which Whittaker pointed out in the pre-climb briefing. We cross our first snowfield and work our way over a rocky outcropping to the second. Now I can see the looming profile of the Disappointment Cleaver, the jagged spine of rock the route is named after. The stars that make up the Big Dipper are suspended over its craggy horizon, and for a moment, the headlamps of an earlier-rising rope team on the ridge add four new points to the familiar constellation.

The ascent to the Cleaver’s base requires a traverse across another snowfield and threading the needle between gaping crevasses and overhanging seracs. Whittaker described this zone as one of the most dangerous sections on the route — prone to both ice and rockfall. The snow here is strewn with Fiat-sized chunks of glacial debris, proof of the mountain’s fierce and sudden movements. Whittaker adjusts our pace and we traverse the area as quickly as possible. The world couldn’t seem more serene — there’s not even any wind — but my heart begins to reverberate inside my chest and skull in time with our hasty steps. Our crossing is a matter of minutes and before I know it the surface beneath my feet changes from snow to stone.

The Cleaver itself presents a steep, technical scramble through sharp andesitic rock. We gain elevation quickly. Sweat drips from my forehead and my crampons screech against the unforgiving stone with each heaving step — as if making it known that they are as out of their element as I am. It’s only when I reach its apex that the ascent seems a blur. We take a much-longed-for break, the white summit in view, its nearness a deceptive mirage.

W

hittaker’s businesses have all been relatively small, with the exception of the RMI, which employs 75 people during climbing season. But that could soon change. His recently launched apparel brand, MtnLogic, is aimed at creating high-performance climbing gear suitable for clients and pros alike. Whittaker is the driving force behind the company, but he’s shored up by the collective knowledge and experience of RMI’s team of 60+ guides — a group that logs hundreds of thousands of vertical feet in alpine environments each year. Every piece of MtnLogic apparel is thoroughly tested by the guide team on Rainier and the tallest mountains in the world to ensure that it’s built to fulfill its intended purpose. “This sounds cocky,” says Whittaker, “but we can build gear as well or better than anyone because we live in it up there. We spend ten thousand days a year [collectively] above treeline. We kind of know what works and what doesn’t.”

To have athletes provide feedback on gear isn’t a novel idea. Brands such as Arc’teryx and Patagonia regularly make use of athletes and ambassadors in product development. Whittaker is no stranger to the process; at various points in his career he served as a sponsored athlete for The North Face, Marmot and Mountain Hardwear. He also played a key role in developing Eddie Bauer’s guide-tested First Ascent line. He describes the process as imperfect, often more for the sake of marketing than for creating the highest-quality gear capable of standing up to prolonged mountain conditions. Whittaker recalls one design review meeting in which the athlete team he was a part of deemed a jacket unusable due to a hood that didn’t fit over a helmet. They were told that a fix wasn’t possible — the piece was already in production. That, to a working climber, was unacceptable.

Mount Rainier is the tallest volcano in the lower 48. Geologists have labeled it as episodically active, meaning that it is expected to erupt again sometime in the future.

Design meetings at MtnLogic operate differently. Whittaker assembles the team — designer, managers and guides — at Base Camp. There’s pizza (sometimes sushi) and plenty of beverages. Every guide who signs on to the program, from first years to veterans, has a voice. Naturally, constructive criticism transforms into heated debate. “There’s yelling, people get pissed. It’s passionate,” says Whittaker. No detail is too small — pit zips are a particular point of contention — and no piece, no matter how far along into development it is, is protected from condemnation. As was the case with a softshell jacket that Whittaker was particularly excited about making. The guides tested it, found it to be heavier than they wanted and refused to pack it on expeditions to Denali. So that was the end of that. Whittaker stands by his word: “If our guys aren’t going to wear it then we’re not going to build it.”

I wore and tested the full MtnLogic 2017 range while climbing Rainier. Every piece performed on the mountain and met the high expectations I held going into the trip. But don’t take my word for it; take the guides’.

Jess Matthews RMI Lead Guide, 25+ summits of Mt. Rainier, 2 expeditions to Denali, Mt. Baker via the North Ridge and Coleman-Deming routes — “We beat our gear up and know the ins and outs of what works for us and what doesn’t. It was refreshing as a guide to sit at the table next to designers and see our feedback directly translated into the design process. I’ve been packing the Alpha Ascender hoody on every single climb this season and I also love our NeoShell Nuker. It feels like a softshell, but performs like a hardshell. I find that it really does breathe, keeps you dry and maintains a better level of comfort temperature-wise while you’re climbing without making you feel clammy. It never leaves my pack!”

Mike King RMI Lead Guide, guides 200+ days per year on Rainier, Denali, Aconcagua, Kilimanjaro, and in Mexico and Peru — “Guides use gear at a level that testers and weekend users simply cannot replicate. We have an understanding of what is functional and thus essential — what is a frill designed to advertise and sell more gear. We use the gear more than any other end user and depend on it in the world’s harshest places to protect us, so why should we not expect the same for the climbers we guide and care for? My favorite piece that is in production is the Nuker Jacket which is made of Polartec NeoShell. It breathes better than any shell on the market, and it doesn’t sound like you’re wearing an empty potato chip bag when you move in the mountains.”

It falls to Diane Sheehan Egnatz, Design Lead at MtnLogic, to take the raw information gleaned from those guide meetings and translate it into functional mountain apparel. Egnatz earned a degree in apparel design from the University of Delaware, just down the road from W.L. Gore, and after a stint of retail work at Eastern Mountain Sports, began designing outdoor apparel for Railriders, the U.S. Special Forces, Eddie Bauer and K2. Egnatz has worked collaboratively with athletes and end-users, but never on a scale with so many opinions at play.