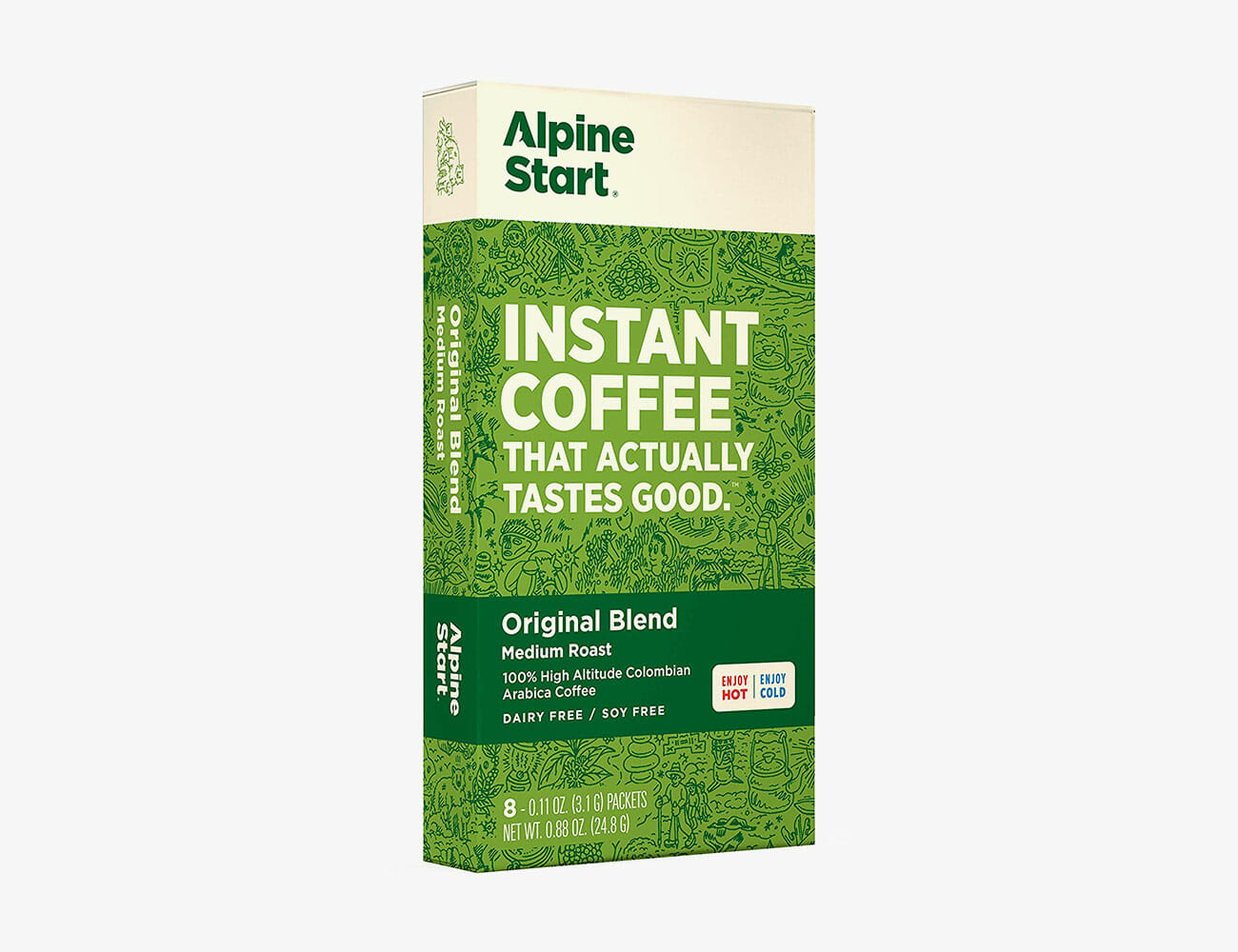

In the mid-’90s, John Martin had a single quote written on a notecard tacked to a small cork board hanging above his desk along with a few autographs and thank-you notes from pro snowboarders. It was his inspiration board. The senior product development engineer for K2 Snowboards wanted to preserve the words of snowboarding pioneer and big mountain legend Jim Zellers, who once told him, “When my kids grow up, they will not be riding soft boots.”

At the time, Martin was developing K2 Clickers, the strapless snowboard binding system that allowed riders to step onto a metal baseplate that interfaced with their boots, without having to sit or bend over to crank down flimsy ratchet straps going across their toes and ankles. The idea was to make transitions from chairlift to riding faster and less cumbersome while building the support into the boot itself, rather than relying on the external plastic “highbacks” of traditional bindings.

Instead of embracing injection-molded plastic and the ability to dial in flex patterns and pivot points like ski boots, the snowboard industry has never evolved past glorified skate shoes that sacrifice durability, performance and innovation. Here’s why…

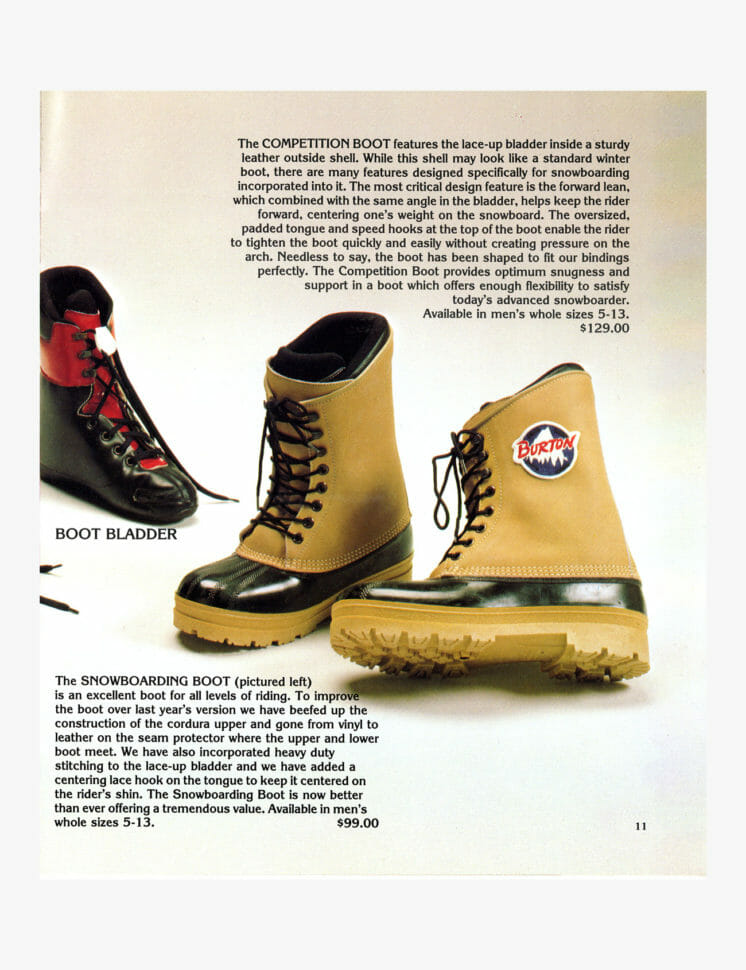

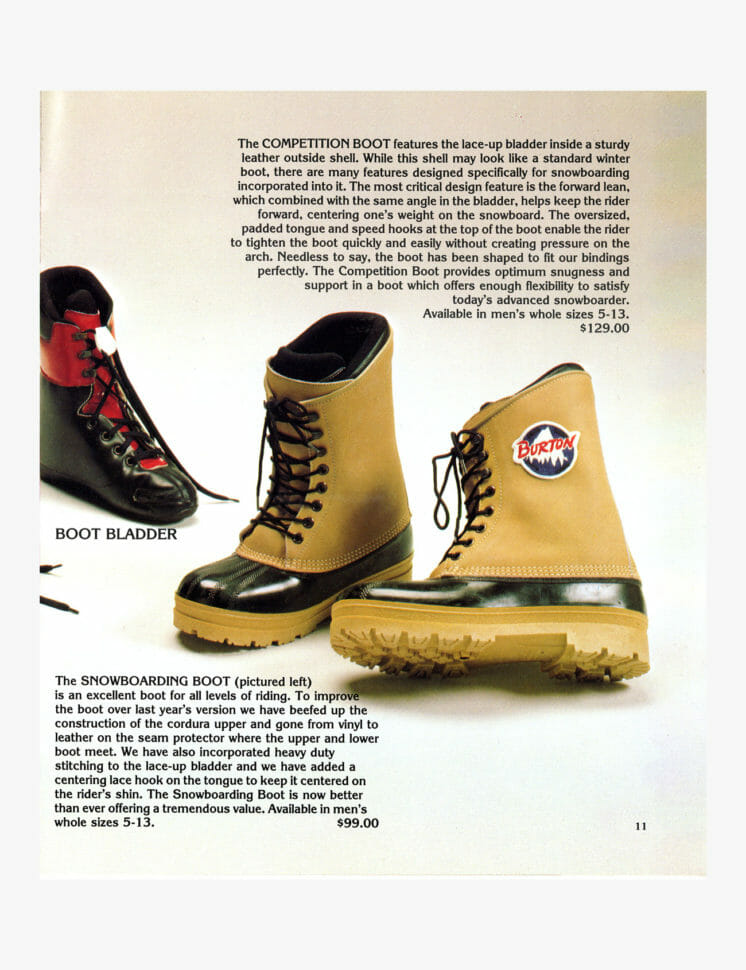

Burton, Switch and a few other companies were leaning toward similar products that provided better comfort, performance and ease of use. For the previous 15 or so years since the dawn of snowboarding, riders had mostly gotten by wearing Sorels or other duck boots beefed up with ski boot liners and other homemade hacks, like pieces of wiffle ball bats or heated-up plastic buckets, for added stability.

As the sport evolved, some snowboarders, including Jim Zellers, modified Koflach mountaineering boots while others embraced hard plastic ski boots on metal plate bindings. The ski boots were popular amongst alpine racers on stiff carving boards with lots of sidecut along with freestyle pros like Damian Sanders.

“Damian has always been an innovator and a tinkerer,” says his brother Chris, former owner of Avalanche snowboards. “He took his new seven-hundred-dollar ski boots into the garage and cut away everything that got in the way of his freestyle riding. Could he have just used a soft boot and highback binding? Not with that board, apparently… We all followed his lead and cut up our boots in different ways. The toe-heel precision of the ‘hardboot/plate binding’ combination transferred energy to the edge in ways other systems weren’t able to do. Watching the team test the gear started to make me feel we weren’t so far from the performance of skiing.”

Damian Sanders showing what a hard boot and a Vuarnet headband can do for a man’s shred game.

Bigger companies like Burton, K2, Salomon and Rossignol all did their own tinkering with this idea. Burton’s Innsbruck, Austria office was still designing and making hard snowboard boots in Italy for their European team well into the ’90s.

“For a few years, [K2] worked with Dalbello on a Clicker system with basically ski boots,” says John Martin, who was involved in ten different snowboard boot patents. “The issue with that was, it was actually harder to put metal hardware into plastic ski boots at the time. It would rip out and be a technical nightmare and ended up being massively heavy.”

Casualties of Culture War

But while R&D labs were poised to continue innovating hard boot and step-in systems, snowboard culture in the ’90s was looking in the opposite direction.

“The hard boots lost out because back in the day, there was that stigma that hard boots were skiing and we didn’t want to be considered anything that’s skiing,” says longtime pro — and K2 Clicker rider — Chris Engelsman.

“Snowboarding allowed us to wear boots we could hike and drive in,” says Sanders. “The boards and bindings were simple and light compared to ski [boots]… And snowboarders weren’t skiers. We weren’t just skiing sideways; we thought we were a revolution. We needed to make it clear: Dad skied. We rode.”

Burton employees used to joke that if founder and owner Jake Burton couldn’t drive his stick shift BMW in a boot, they weren’t going to make it.

This tribal sense of defiance — of marginalized snowboarders bucking ski areas’ efforts to ban them from the precious slopes of snobby skiers — carried over to the shop experience. Young, rebellious boarders didn’t want to spend twice as much money on boots that made you walk like a giraffe and required heat molding and custom fit footbeds and a bunch of other expensive aftermarket crap to prevent them from being torturously uncomfortable. The first thing skiers did after stumbling up the steps to the après bar was remove their boots and massage their sore, swollen feet. Meanwhile, snowboarders were already dancing in the soft, pillowy boots they’d been riding in all day.

Early Burton boot ad

“People wanted comfort when they put the boot on in the shop, even if it broke down in a few seasons,” says Martin. “So companies lightened up their requirements for durability.” Northwave was known for boots packed with so much soft padding they felt like slippers, which propelled sales despite their rapid deterioration.

“Snowboard boots are the one part of the three-part package that you can try in the store,” says Eric Gaisser, longtime director of the boot category at Burton. “ThirtyTwo came out with an EVA rubber sole that was even lighter and less stiff… We used to joke that these kids at Mt. Hood would barely even tie their boots.” Burton employees also used to joke that if founder and owner Jake Burton couldn’t drive his stick shift BMW in a boot, they weren’t going to make it.

Hard boots were still alive and well in Europe, but snowboarding was always a US-based revolution, with surfing and skateboarding culture leading the trends. And the bulgy, glorified skate shoe was cementing itself as the standard boot model for years to come.

In 1999, K2 acquired Seattle rival Ride Snowboards — along with their notoriously anti-Clicker staff, who influenced the decision to put more money into strap systems and less into step-ins. The boots still lacked the articulation of regular boots being made with softer and lighter foam soles and didn’t get the design resources they needed to improve.

“The Clickers died a slow death and sales tapered,” says Martin.

Hard boots were still alive and well in Europe, but snowboarding was always a US-based revolution, with surfing and skateboarding culture leading the trends. And the bulgy, glorified skate shoe was cementing itself as the standard boot model for years to come.

![]()

From Snow Beach, edited by Alex Dymond, published by powerHouse Books

“With snowboarding culture, I always found it hard to introduce new technologies,” recalls Greg Dean, who led Burton’s design engineering group from 2003 to 2008. “It seemed like there could have been the next step forward in step-ins by fixing the comfort and performance, but the industry just went backwards and adopted the old system. There’s a certain amount of hero worshiping with the pro riders and they’re very influential over what products can make it into the marketplace… In snowboarding, graphics drove sales more than anything. We’d put a great new technology into a board, and I saw more people getting excited about the new graphics of that year.”

Aside from lacking the all-important cool factor, hard boots have always been extremely expensive to manufacture. The cost of a mold for each size of each boot model can be close to $100,000. Why spend all that money on new tooling and injection-molded plastic when you can make cheaper, oversized sneakers out of leather, stitching and glue and pay pros to say they’re the best? Then they’d fall apart after a season or two of hard riding and customers would have to buy a new pair.

Modern-Day Mods

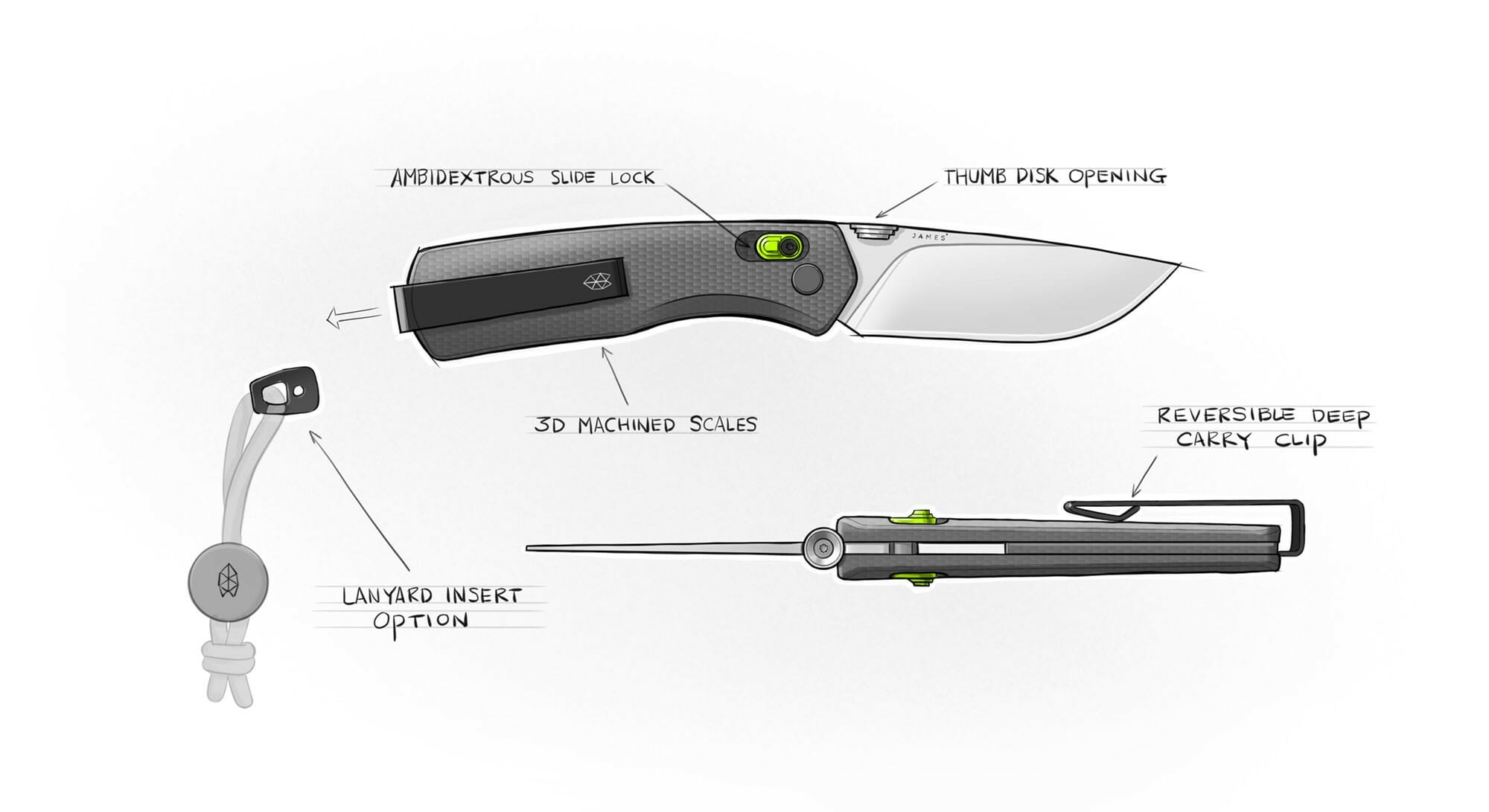

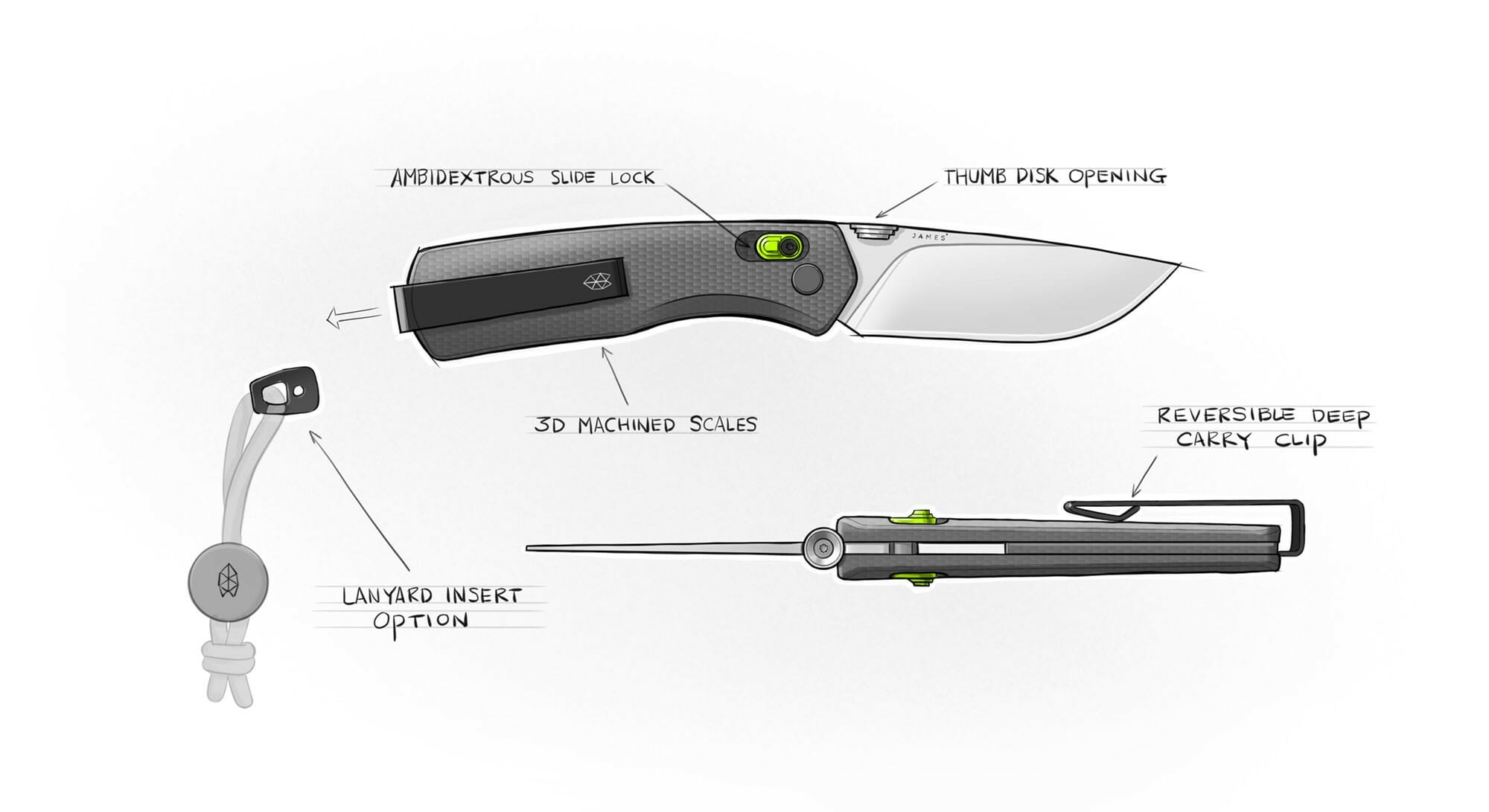

Fast forward 20 years and snowboard boots don’t look all that different. Most innovations have focused on lacing and closure mechanisms like BOA dials and Burton’s two-part Speed Lace system, along with a few internal ankle-harnessing features. Very few, including the ThirtyTwo MTB, Deeluxe Spark XVe and Fitwell Backcountry, have stiff (albeit heavier) Vibram soles and/or walk modes, but they’re still using leather, stitching and glue — and losing their structural integrity over time.

Relegated to the bottom shelf at trade shows in early 2019, the Ground Control is a new soft boot upper on a hard boot sole released by Austria-based Deeluxe to appeal to the resurgent carving market. The hybrid boot made a small splash with its potential for precision in power transfer, though its BOA dial, heavy weight (close to five pounds each), and incompatibility with splitboard setups are major limitations — and it lacks the precise flex patterns achievable with ski boots. Still, it’s a start.

The Deeluxe Ground Control boot

“Snowboard boots had revolutionary design updates that happened more than a decade ago and since then, they’ve kind of stopped evolving,” Michael Fox, a longtime snowboard boot developer who’s worked for K2, Burton, ThirtyTwo, DC and Adidas, said in an interview with German sneaker youtube channel Turnschuh.tv in 2016. “I feel it’s really time for the snowboard boot to take another evolutionary step.”

Ski boots, meanwhile, have reaped the benefits of much lighter, more durable plastics, mountain-ready outsoles, and sophisticated buckling systems with articulating walk modes and even lateral flex profiles. The technology has improved so much that in the backcountry, where snowboarders use splitboards to ascend mountains before riding down them, there’s been a surge of riders modifying alpine touring ski boots for snowboarding.

“Skiers had leather boots a long time ago, but they don’t anymore for good reasons. Someday snowboarders might realize how much extra energy they’re expending with soft boots in the backcountry, trying to kick steps and sidehill without any leverage.”

These setups can shed up to 2.5 pounds per foot, leverage better edging on uphill traverses and attach to crampons much more securely than soft boots, allowing riders to kick steps into steeper slopes when bootpacking and, with the right modifications, ride in a more predictable and precise way than they can in soft boots. Weight, durability and performance matter a lot more in the backcountry than during in-bounds resort riding, and, as Dean notes, “the backcountry folks have always been more in tune with new technology.”

But even top-level splitboard guides and splitboard mountaineers (who aren’t getting dropped directly on top of their lines from helicopters) still have to spend hours modifying hard boots to get them to work for snowboarding. This DIY process involves relocating buckles to better hold the ankle in place, dremeling release cuts in the lower shell and drilling holes in the cuff to enhance flexibility, and altering the walk mode tolerance to allow a level of front-to-back mobility that ski boots aren’t designed to have but snowboarders demand.

The Atomic Backland Ultimate boot

Despite all this garage ingenuity, the reality is that, according to the Snowsports Industry Association, 81.2 percent of the 7.8 million snowboarders in the US ride 10 or fewer days a season, mostly in-bounds — not 150 days in technical mountaineering terrain. As it stands, they’re unlikely to spend five of those days tweaking and dialing in the fit of a new boot, and they’re still more likely to buy the comfiest thing they slip their foot into at the store.

Southern California skate culture and what’s left of snowboard media is still driving most of the industry’s influence alongside pro freestyle riders, which leaves little incentive for companies to innovate expensive boots that don’t need replacing after a couple seasons. The industry is lagging to meet the boot demands of splitboarders, but backcountry touring is such a small subset of snowboarding that it’s of little surprise.

The Path Not Taken

To this day, some see hard boots as the path not taken, leaving snowboard boot technology stranded in the past while boards and bindings progressed. What would we be riding now if we had successfully integrated the whole binding support system into the structure of the boot over the past two decades?

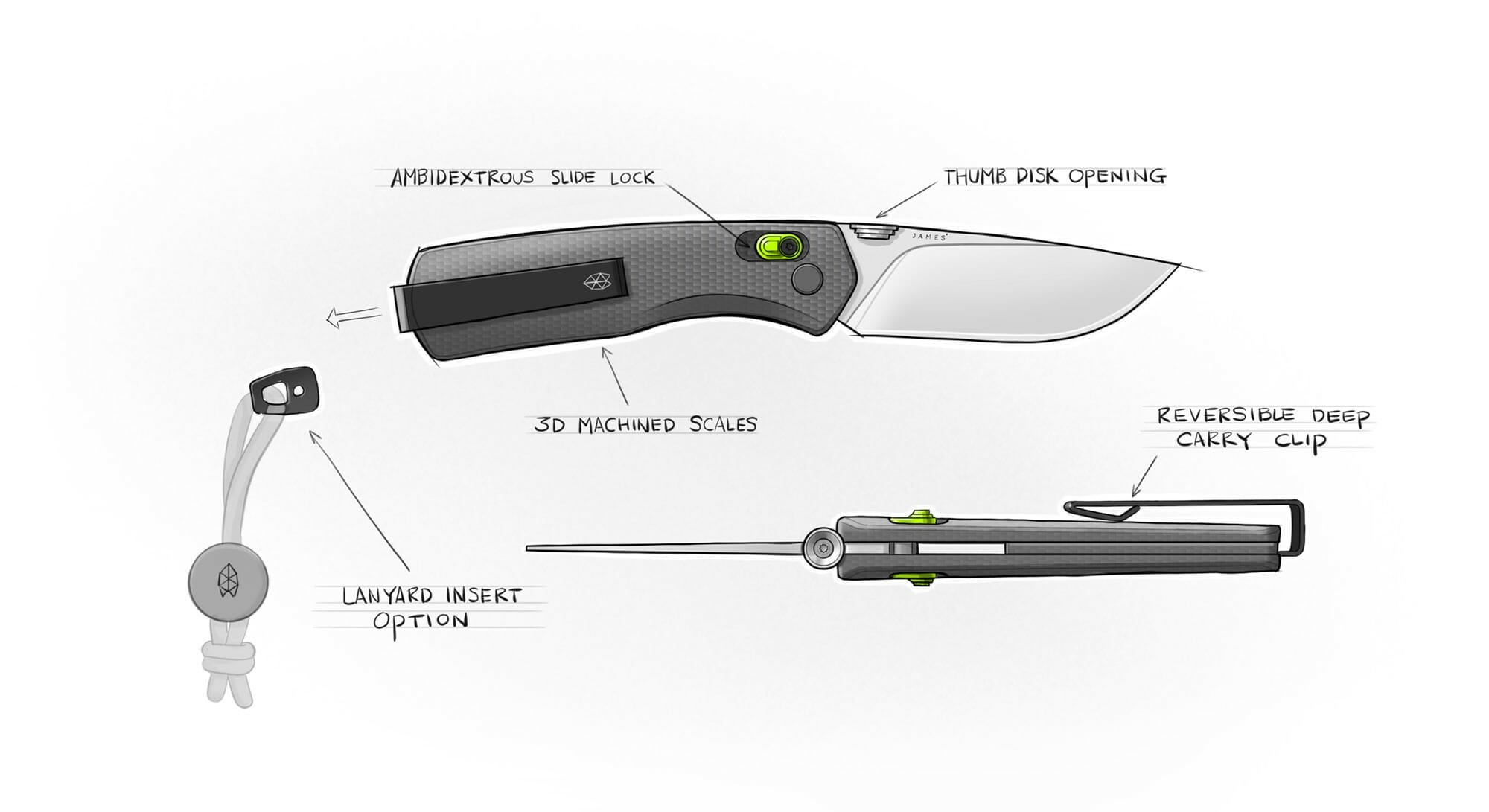

John Keffler has an idea. The Colorado-based father of three and rocket scientist on NASA’s Mars Rover Project somehow manages a side hustle running Phantom Splitboard Bindings, made for hard boots, with a CNC machine in his garage. In addition to his custom-designed splitboard connector hooks, toe pieces for touring, heel risers (for added leverage on steeps), fixed angle baseplates (to save weight), and heel and toe bail bindings with no straps, Keffler has his own hard boot modification kit for the Dynafit TLT6 boot and a spring-loaded forward/backward flex mechanism for the Atomic Backland.

His whole boot and binding system is several pounds lighter than soft boot options, more durable, faster to lock in — and he believes he can achieve the same amount of flex found in any soft boot on the market with the proper modifications. “Skiers had leather boots a long time ago, but they don’t anymore for good reasons,” he says. “Someday snowboarders might realize how much extra energy they’re expending with soft boots in the backcountry, trying to kick steps and sidehill without any leverage.”

![]()

Courtesy of John Keffler

Keffler collaborated on a custom toe piece with Spark R&D, one of two main splitboard binding companies for soft boots that continues to develop their own hard boot system to meet this creeping demand.

While Keffler’s technology is years ahead of anything being mass produced on the market, his resources and support are limited. Ski boot companies could easily swap out a few parts in their existing boot configurations to work great for snowboarding, but why would they go through that hassle to maybe sell a few thousand units? The snowboard industry is still too hampered by the technology-blind cool factor that leaves them far too insecure to be seen wearing anything that looks like a ski boot.

Although Phantoms are primarily used for splitboarding, legendary freestyle pro Chad Otterstrom can be found cruising through the terrain park in modified Atomic Backlands and Phantoms while jibbing rails, boosting out of the halfpipe, and spinning and flipping off jumps of all sizes. Comments on the videos range from awe to confusion, with tributes to Damian Sanders appearing alongside the words of freestyle pro and Vans team rider Pat Moore, who jeered: “What the hell are you riding?”

Erig Gaisser at Burton thinks there could be a future in a hybrid sort of boot, especially with advancements in 3D printing allowing them to try out new prototypes the same day they’re conceived.

“For that to come out, it’s going to take someone who is a big player like us or Salomon or K2… someone with deep pockets to invest in some development like that,” he says. “A smaller brand wouldn’t spend the time to do that.”

In 2017, Burton brought back a major update to their step-in system called the Step On with a smoother interface that’s less likely to get clogged up with ice and snow but still uses a soft boot with a soft sole and external binding highback.

Will progressive hard boot technology in the niche backcountry market make enough of a splash to push the snowboard boot industry into a better product for the future? Will the masses come to appreciate how much a walk mode saves your knees while trudging through the parking lot or how much power transfer you get from riding with a stiffer sole?

“The geometry of a snowboard is pretty set, but there’s still a lot of options for how you attach yourself to the board,” says Dean.

“The market is more ready than ever for hard boot technology,” adds Martin. “[Ski] boots have gotten softer… it’s a matter of what company is going to get into that.”

Ultimately, the sway of influencers driving consumer demand will supersede R&D potential and available technology. What would it take for professional icons like Travis Rice, Bryan Iguchi or Jake Blauvelt — who all get paid to push their own pro model soft boots — to join the call for a high-performance, flexible, comfortable plastic boot for the downhill? In the words of Jim Zellers: “If the pros are gonna do it, it’s gonna happen. If Jeremy Jones ever switched over, it’s really about what comes out of his mouth.”

Meanwhile, Zeller’s kids are in college and they’re still riding soft boots.

Note: Purchasing products through our links may earn us a portion of the sale, which supports our editorial team’s mission. Learn more here.