Everything You Need to Know Before You Buy a TAG Heuer Watch

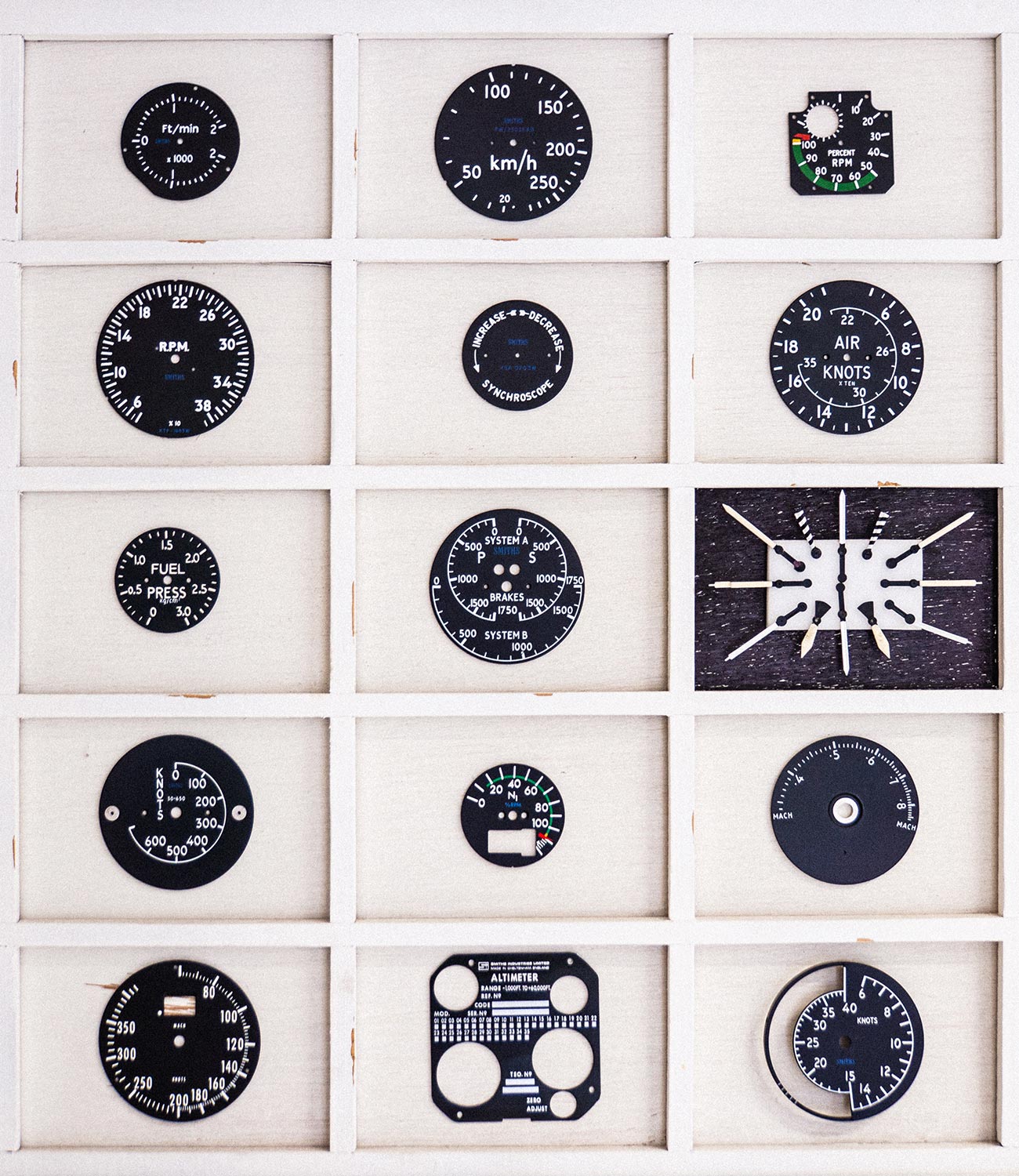

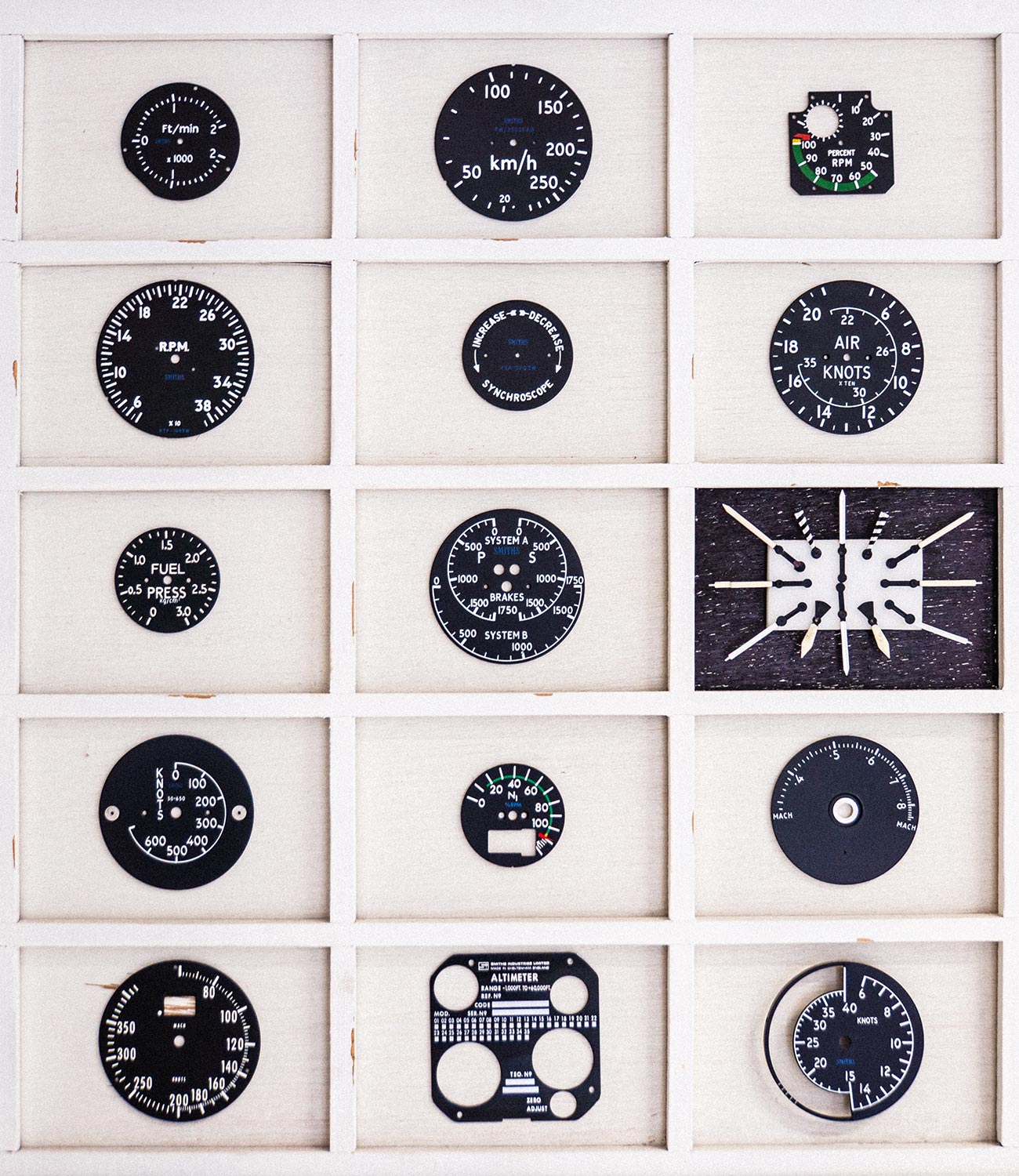

In 1860, long before Techniques d’Avant-Garde (TAG) purchased a majority stake in the company (which was subsequently gobbled up by the LVMH Group), Edouard Heuer set up his eponymous watch manufacturing company in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. Soon after, he was patenting unique mechanisms, some of which still operate in many mechanical wristwatches today. However, Heuer was most famous for making chronographs, starting with dashboard clocks used in both cars and planes. Then, in 1914, Heuer offered their first wrist-worn chronograph.

By the 1960s, Heuer watches were so thoroughly enmeshed with auto racing that it’s hard to find a photograph of Formula 1, Indy, or GT racing from that era in which their logo isn’t visible. Specifically, Heuer Autavia and Carrera chronographs were de rigueur among drivers. When Steve McQueen sported a square Heuer Monaco during his all-too-short racing career, both man and watch were immortalized in photographs that have become enduring templates for men’s fashion. McQueen’s 1971 film, LeMans, endowed Heuer’s racing pedigree with a dose of Hollywood’s ineffable mystique.

Heuer, like so many other Swiss watch makers, struggled through the Quartz Crisis of the 1970s, resulting in a situation dire enough that the company went up for sale. TAG was added to the name in 1985 when the holding company Techniques d’Avant Garde acquired the brand. For those of us who remember the Regan Era, Tag Heuer — which sponsored sailing, golf, tennis, and, of course, auto racing — became as much a status symbol as Rolex among well-heeled preppies who grew increasingly unabashed of displaying their wealth. Men and women both strapped on sporty two-tone Tag Heuers, popped the collars on their Lacoste shirts, tied cable knit sweaters around their necks, and sparked up Marlboro Lights in unruly Porsche 911s.

As grunge and (at least the veneer of) financial humility came into vogue during the 1990s, those 1980s associations haunted TAG Heuer enough that the brand began to drop TAG from some of its retro-styled watches, initiating what remains today a coveted section of their catalog that harkens back to the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. But most of TAG Heuer’s offerings during the 1990s tended toward the trends, with increasingly larger timepieces for men and relatively dainty models for women. Then in 1999, LVMH bought TAG Heuer, pumped in enough capital to revive the brand’s ubiquity, and by the 2010s was pushing “connected” TAG Heuer watches intended to compete with the Apple Watch. But Tag Heuer also pushed their legacy to the fore with retro-styled mechanical models and tasty reissues.

This bifurcation between forward- and backward-looking watches isn’t unique to TAG Heuer, but it does seem pronounced with this brand. For those who like vintage-inspired timepieces, Heuer has recently released a slew of new models that will satisfy; for those who like their envelope pushed, TAG Heuer offers a robust catalog of decidedly modern watches.

The Monaco

Featuring an immediately recognizable square case as well as an automatic movement and hip, colorful accents, the Monaco has become an automotive icon (as well as a horological one) since its inception in 1969, when it was named after the famed Monaco Grand Prix.

The Monaco Automatic

Square, iconic, and the one that Steve McQueen made famous. These chronographs have heaps of presence, and are true conversation starters. Nab it with the classic Calibre 11 movement, or with a more affordable Calibre 12 — or go all out with the newer Calibre Heuer 02, which boasts an 80-hour power reserve.

Size: 39mm

Complication: chronograph and date

Price: $5,400+

The Monaco Quartz

This is an affordable way into the Monaco line, offering all the classic styling of the original in but with a less expensive quartz movement.

Size: 37mm

Complication: date

Price: $1,750-$2,450

The Autavia

Somewhat confusingly, the modern Autavias look like dive watches, but also harken back to the original dashboard clocks Heuer built for planes and cars, which were called Autavias (“Automobile” plus “Aviation” = Autavia). Even more confusingly, there is indeed an “Autavia” within the Heritage Collection that hearkens back to the original Autavia chronograph of the 1960s.

Heuer Heritage Calibre 02 (“Autavia”)

As part of their Heritage series watches, the Heuer Heritage Calibre 02 Autavia recalls the 1960s, when these three-register chronographs helped time laps around the world. Best of all, the 12-hour bezel can conveniently be used to track a second time zone.

Size: 42mm

Complication: 3-register mechanical chronograph

Price: $5,300-$6,050

The Autavia

Though these timepieces clearly look like dive watches (rather than rally timers), one way to reconcile this seeming contradiction is to acknowledge that the modern Autavia doesn’t fall back on tired automotive aesthetic cues, but forges a vibe that’s uniquely vintage Heuer. These watches are chronometer-certified mechanical watches that come in at a relatively affordable price point.

Size: 42mm

Complication: time, date (COSC Certified Chronometer)

Price: $3,000-$3,350

The Aquaracer

Though not originally known for dive watches, by the 1980s, Heuer was competitive in this field, keeping pace with Rolex and Omega. Today’s Aquaracers come in many sizes and colorways, and they come with either mechanical or quartz movements. Some of their two-tone models look like their 1980s offerings, while the standard models are decidedly modern.

Aquaracer Standard Quartz

These watches are largely indistinguishable from their mechanical counterparts, but with a vast array of available sizes and colorways — all the way down to 32mm with diamonds and two-tone metals — there’s here something for everyone.

Size: 32mm; 35mm; 41mm; 43mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $1,350-$4,700

Aquaracer Standard Mechanical Caliber 5

These time-and-date watches offer 300m of water resistance and styling cues that are 100% marine-inspired. A vast array of colorways and two masculine sizes assure that there’s something for everyone.

Size: 41mm; 43mm

Complication: time and date, available in both mechanical and quartz versions

Price: $2,200-$2,950

Aquaracer Mechanical Chronograph Caliber 16

Essentially the same as the standard mechanical Auaracer, the chronograph version has a densely packed dial with three registers.

Size: 43mm

Complication: time, chronograph, date

Price: $3,300

Aquaracer Quartz Chronograph

The layout of the sub-dials changes with these watches, but in terms of style and function they remain very close to their mechanical cousins.

Size: 43mm

Complication: time, date, chronograph

Price: $1,650-$2,300

The Carreras

The Carrera label is an enormous umbrella under which a vast array of models exist, from highly technical skeletonized chronographs to dainty diamond-encrusted women’s models. We’ve broken the Carreras down for you as either chronographs or time-date models, and from there we break them down according to their movements.

Carrera Chronographs with 02 Movement

The 02 movement lends this chronograph all the cutting edge technology you’d expect from a modern mechanical Heuer. There’s a wide selection of 02 models to choose from, including a GMT, and generally speaking they’re going to look much like their more complicated 02T cousins, but without the heavy price tags.

Size: 43mm or 45mm

Complication: chronograph (one model includes a GMT)

Price: $5,350-$13,100

Carrera Chronographs with O2T Movement

Large, expensive, technical-looking watches with the 02T in-house chronograph movement that features a tourbillon, a type of escapement in which the balance spring rotates in order to counter the effects of gravity. This is an incredibly complicated way to improve accuracy that originated in the 18th century, but which holds the undying fascination of today’s horologists. The price of these watches is high, but in the world of tourbillons, they’re incredibly well priced — relatively speaking, of course.

Size: 45mm

Complication: tourbillon, chronograph

Price: $17,000-$25,500

Carrera Chronographs with Caliber 16 Movement

A more modest look and size connects these chronographs to Heuer’s storied automotive past.

Size: 41mm or 43mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $4,150-$4,750

Carrera Chronographs with Caliber 16DD Movement

DD stands for Day Date, and the addition of the weekday has a surprisingly powerful impact on the vibe of a watch; it feels decidedly 1960s-70s, the era when the day-date complication was very much in vogue. Perhaps drug-fueled disco nights made keeping track of the weekday difficult?

Size: 43mm

Complication: time, day, date

Price: $4,800-$5,300

Time & Date Carreras with Caliber 5 Movement

Basic in design and features, but filled with the same 60s styling as their more complicated counterparts, these watches are great all-arounders for those who like an automotive vibe on their wrist.

Size: 36mm, 39mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $2,500-$4,650

Time, Day/Date Carreras with Caliber 5 Day-Date Movement

A little larger and a little vibier with the day-date complication, these automatic mechanicals are long-standing essentials for Heuer.

Size: 41mm

Complication: time, day/date

Price: $2,700-$3,000

Small Carreras with Caliber 9 Automatic Movement

These diminutive watches help break the industry-wide assumption that women only want quartz movements.

Size: 28mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $2,200-$6,400

Carreras with Quartz Movements

Less expensive, more accurate, and never requiring the level of service that a mechanical watch will, quartz-powered watches are the ideal for many watch buyers. These quartz-powered Carreras come in a variety of sizes and styles that cover the gender spectrum fully.

Size: 32mm; 36mm; 39mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $1,550-$5,900

Formula 1 Series

Back in the 1980s, the Formula 1 was the watch to have among sport-oriented folks who understood that durability and pizzaz didn’t have to mean buying a Rolex. Today the Formula 1 models represent a similar spirit. They’re relatively affordable, very sporty, waterproof, durable, and often quite colorful.

Formula 1 Chronographs with Quartz Movements

Nearly half the price of their automatic counterparts, these watches come in a variety of colorways, all of which are vibrant and sporty.

Size: 43mm

Complication: time, date, chronograph

Price: $1,300-$2,100

Formula 1 Chronographs with Caliber 16 Automatic Movements

At the top of the Formula 1 series, these represent a sporty and modern alternative to the Carrera automatic watches.

Size: 44mm

Complication: time, date, chronograph

Price: $2,800-$3,200

Formula 1 Time & Date Quartz Models

Some of TAG Heuer’s most affordable watches, these represent an entry point for the brand but don’t sacrifice durability and sportiness. With robust water resistance ratings, these are ready to go anywhere and do anything — and they’ll look sharp, too. Styles and sizes are wide-ranging.

Size: 32mm; 35mm; 41mm; 43mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $1,000-$2,150

Formula 1 Time-Date Models with Caliber 5 Automatic Movements

Basic models featuring automatic movements and 200m of water resistance, these qualify as dive watches and harken back to the very popular Formula 1s of the 1980s.

Size: 43mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $1,800-$2,050

Formula 1 Time-Date Models with Caliber 6 Automatic Movements

Moving the center-mounted running seconds hand to a sub-dial at 6-o’clock, these watches have a vibe all to their own.

Size: 43mm

Complication: time and date with seconds on sub-dial

Price: $1,750

Link Series

These do not link to your smartphone; rather, “link” refers to the bracelets, whose curvy interlocking shapes are distinctive to TAG Heuer (how many watch brands can claim that?). While many brands race into the luxury steel market today, TAG Heuer has been right there for decades.

Link Chronographs with Caliber 17 Automatic Mechanical Movements

This is a sports watch you could wear with a suit, or jeans and a tee, or anything in between.

Size: 41mm

Complication: time, date, chronograph

Price: $4,500

Link Time & Date With Caliber 5 Automatic Mechanical Movements

Sporty yet elegant, these watches are solid candidates for the one-watch collection.

Size: 41mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $3,000

Small Link Quartz Watches

Styled as a proper alternative to the Lady Datejust from Rolex, but priced far below, these watches get a ton of wrist time on women who know how to rock a casually elegant look while striking a good value.

Size: 32mm

Complication: time and date

Price: $1,650-$4,450

Connected Modular Watches

TAG Heuer was at the forefront of the Swiss efforts to get watches talking to smartphones. The ubiquity of the Apple Watch has put stress on this approach for Swiss brands who dared, but there’s much to like about a connected watch that doesn’t look like everyone else’s. Configurable in myriad styles and able to display even more watch faces to match, these are interesting alternatives for those who actually want to Think Different.

Size: 41mm or 45mm

Complication: connected digital module

Price: varies widely based on your chosen configuration