N

orthfield, like many towns in Vermont, is small. Even the valley it sits in, an impression carved out over centuries by the Dog River, is small, at least in comparison to the more-famous Mad River Valley, which routes its way through the Green Mountains seven miles to the west. The population of Northfield is just over 6,200. And yet, Northfield is somewhat famous. Famous for the local military university situated at the southern end of town, and for its five covered bridges (there are 100 or so in the state), but perhaps more so now for the product that comes out of the mill at the end of Whetstone Drive.

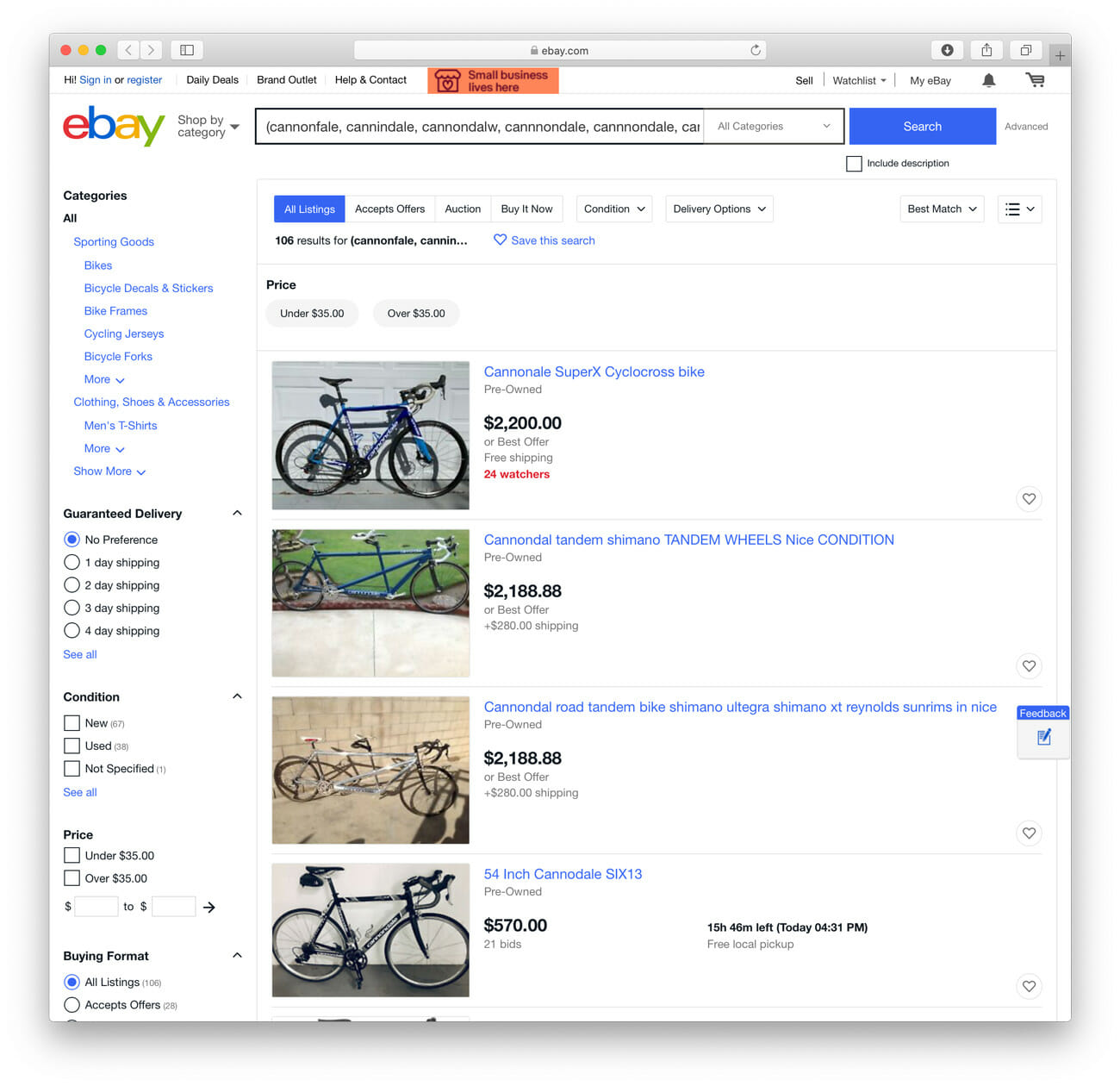

That mill is called Cabot Hosiery, and its product is the Darn Tough sock, the toughest sock in the world. Darn Tough has been in business since 2004, when Ric Cabot, a third generation sock producer, found himself perched on top of the trap door of bankruptcy with a mill, 35 employees and a small army of sock knitting machines. In the two decades that preceded that moment, Cabot Hosiery had been a private label manufacturer producing socks for Gap, Banana Republic and a host of other big name brands.

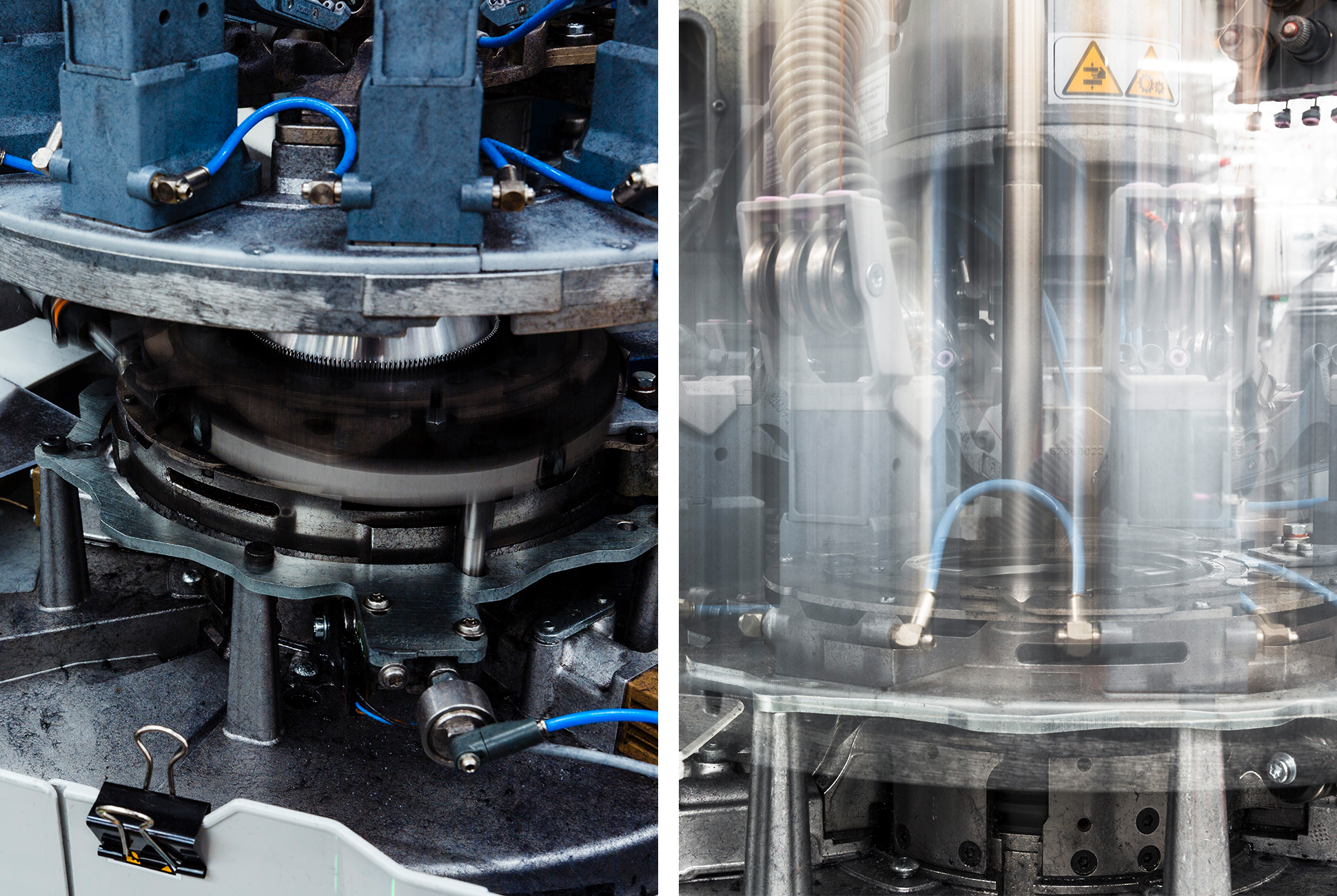

“As opposed to giving up, I tried to figure out a way to keep it going,” says Cabot. “I figured with my three generations of sock making know-how and experience” — Cabot’s father and grandfather were also in the business — “and our own factory, a workforce, the equipment and the beginnings of a raw materials library, if I couldn’t make the best sock out there then no one should be able to,” he says. So he and a colleague named Harvey Stabene took apart one of the Italian-made knitting machines, modified it, and put it back together. Then they knit a sock.

“…if I couldn’t make the best sock out there then no one should be able to,” says Cabot.

Since that time, Darn Tough has grown into a business worth over $40 million. Now, the mill at Cabot Hosiery contains 208 of those modified machines, and they’re running 24 hours per day, five days a week. They collectively knit thousands of socks per day, and it takes 250 employees to keep the mill running at full steam.

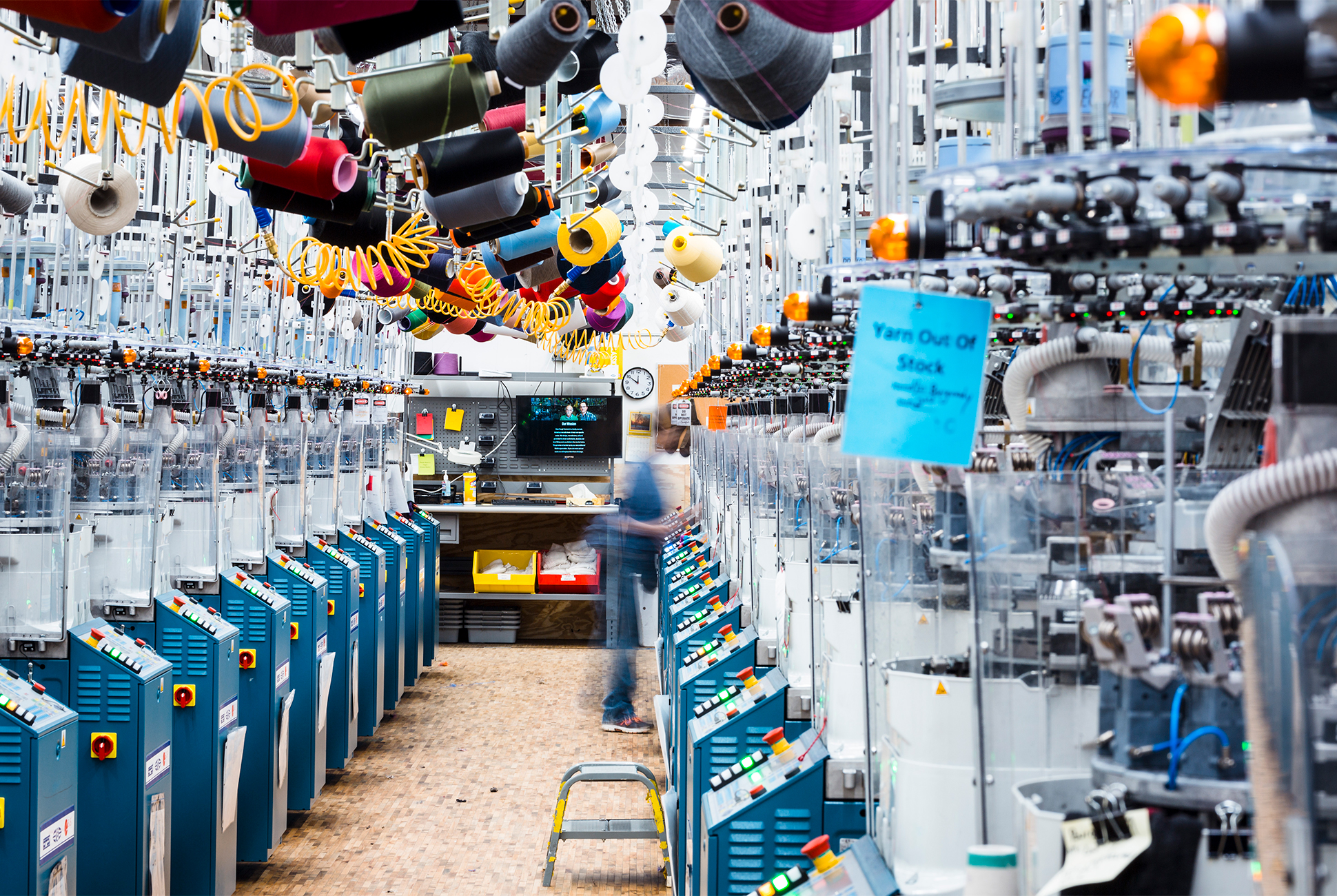

The foyer of the mill is spartan. There’s a check-in desk with a bulletin board and hallways leading to sets of offices. It’s normal, quiet, but head through a set of doors and the ambient volume ticks up two notches. Take a left through another set of doors and enter the vast space where the knitting happens, and it jumps to 11. The scene inside is Willy Wonka meets mass industry; a world simultaneously dominated by harsh chrome and vivid color. The ground is filled with boxy knitting machines; the air above a tangle of bright yarn, furiously spinning to depletion as the needles perform their work.

The record of Darn Tough’s growth can be traced on the knitting room’s floor; as the company expanded it purchased more machines and knocked down walls to add new rows of them — called sets — to the fleet. During the process, new flooring was added, but not to match. Last year, the company grew by over 40 percent.

The air is filled with invisible dust made up of wool and nylon fibers — a force that the staff is continually at war with for the prevention of flash fires. Adding its hum to the constant drone is a pressurized ventilation system that sucks as much of the lint and clippings out of the room as possible. The negative pressure created by it used to produce an almost vacuum-like seal on the entry into the space, and an open window would create an immense WHOOSH. Now, fresh air is pumped in to even it out, but remnants of the materials used to create socks are omnipresent.

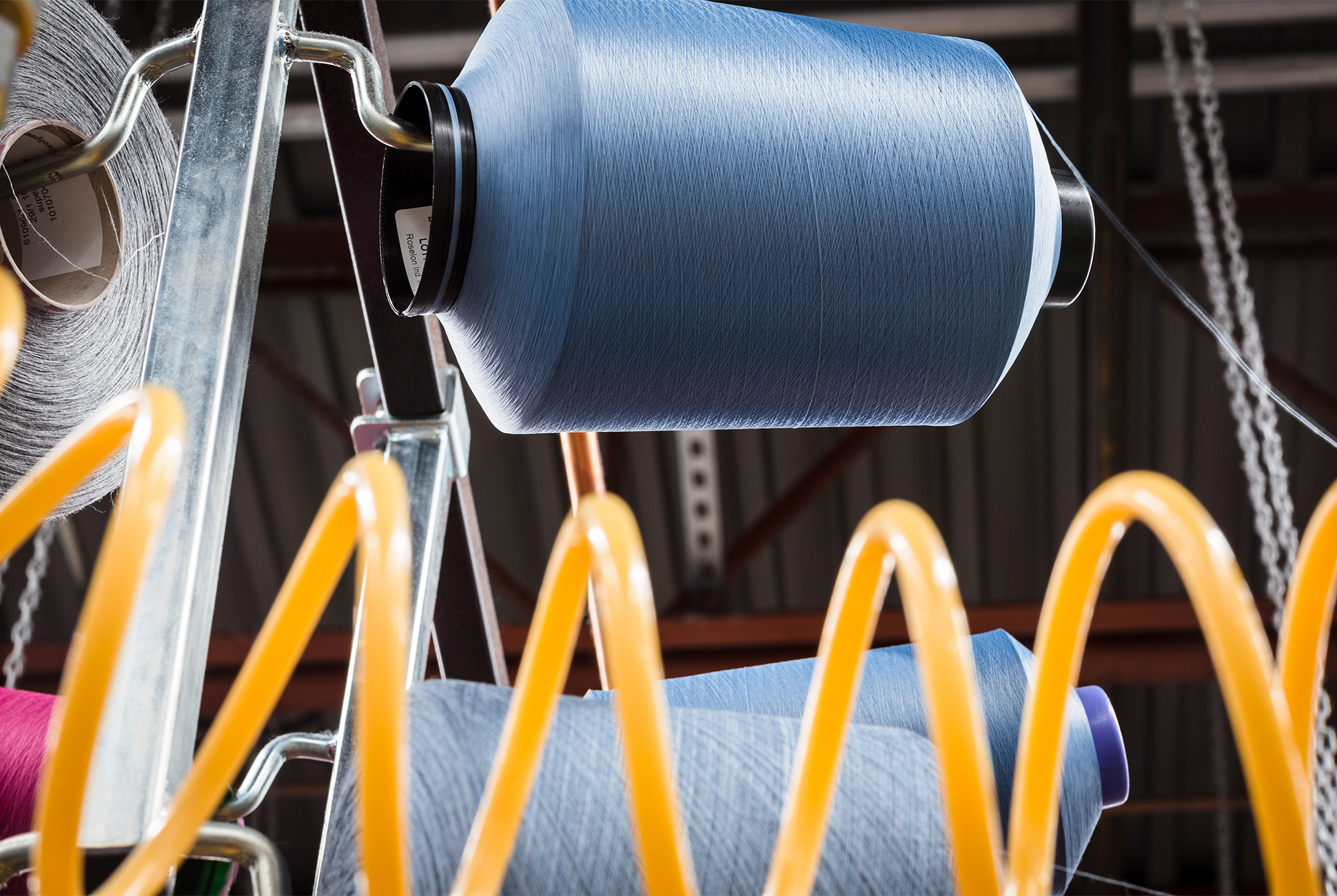

Darn Tough uses merino wool as its primary ingredient, so technically, each sock starts as fiber on a sheep’s back. Those fibers are harvested during shearing and subsequently processed into what’s called a strand. It’s important to note that not all of these strands are the same — some companies will combine the merino ends with nylon ends to create a blended strand, or use fewer ends to create a less durable strand. “We use only fine-gauge merino wool, which means we pack more ends into a strand than our competitors,” says Courtney Laggner, Marketing Manager at Darn Tough.

“Those machines are equipped with 168 needles and can stitch together a sock — there are 1441 stitches in each square inch of a Darn Tough sock — in as little as 45 seconds.”

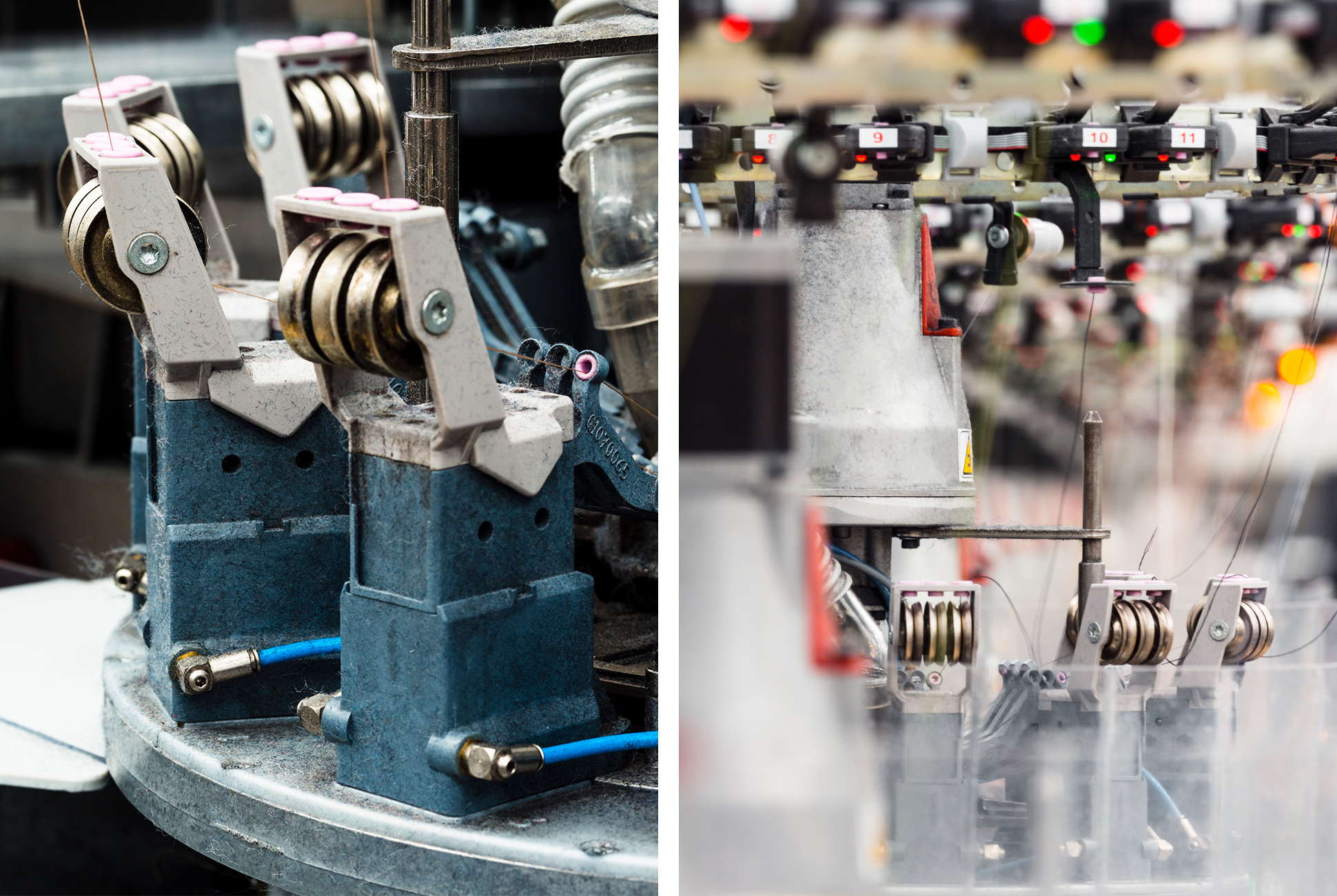

The thread is wrapped around spool-like objects called cones, which hang above-head on armatures that are arranged between and over the knitting machines. Those machines are equipped with 168 needles and can stitch together a sock — there are 1441 stitches in each square inch of a Darn Tough sock — in as little as 45 seconds (tall and heavily-cushioned mountaineering socks take the longest, roughly three and a half minutes).

The knitting machines are cared for and maintained by technicians who make sure that they’re running efficiently, and constantly. If one of them “goes down,” a light will turn on to notify the team that it needs attention. A machine can go down for a number of reasons — a broken needle or a cone that’s run of out of yarn are common instances.

The machines are also monitored by another computer — a “massive mother brain” that audits and measures all the data associated with the intake of raw material and the output of a sock. Because even though each machine is technically identical, each one also has unique character traits. “There are machines that knit certain styles better,” says Laggner. For instance, one machine might be able to knit hiking socks slightly faster than another, or with fewer errors. These specialties are identified, and the machines wind up assigned to particular socks.

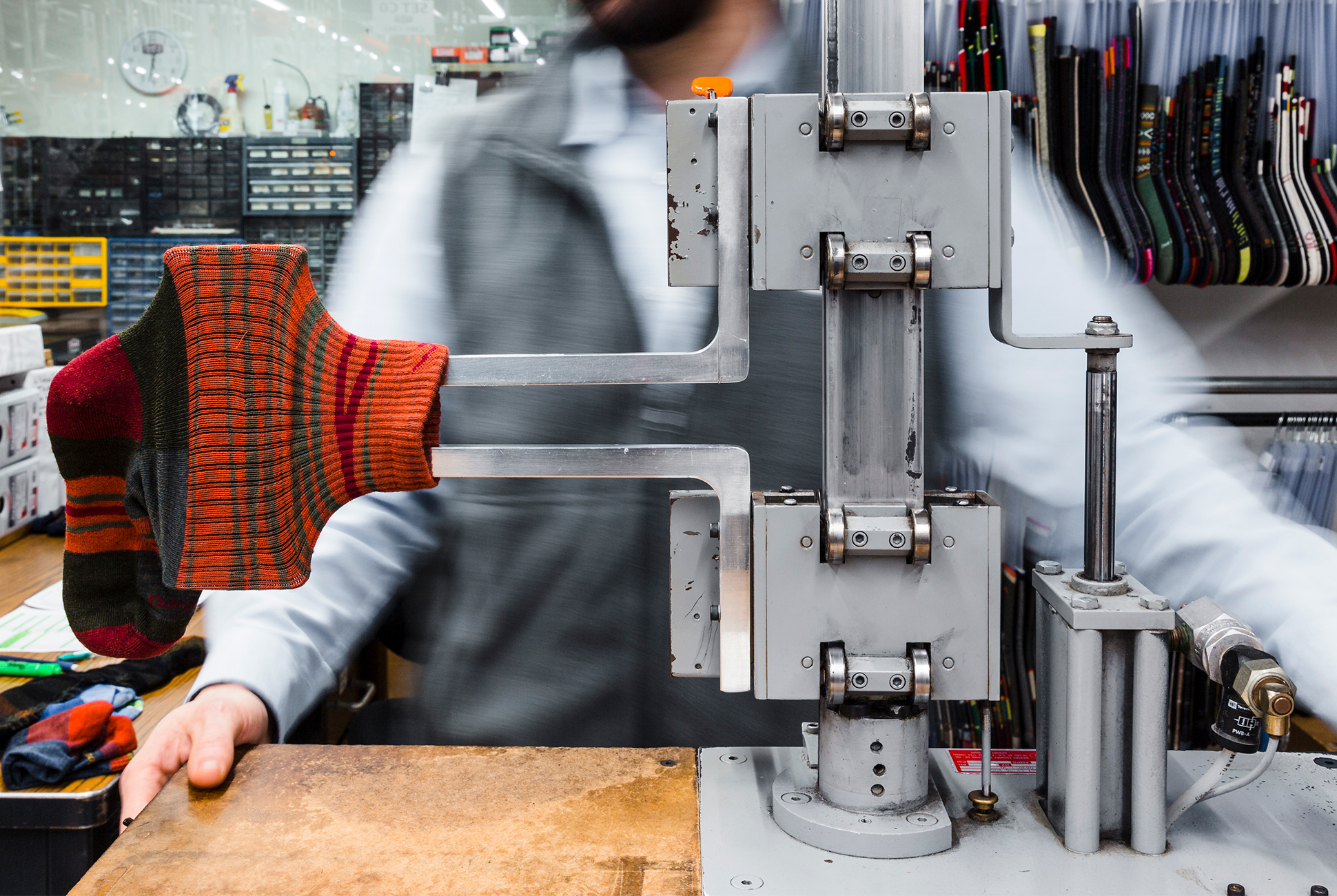

The key to Darn Tough’s class-leading durability is the customized configuration of these machines that Cabot and Stabene developed, and how they integrate the different types of materials into a sock during the knitting process. But those are secrets kept, like a golden idol in a booby-trapped temple, within the walls of the mill. Not so confidential is the other half of the Darn Tough recipe: a meticulous and exhaustive process of checking each sock repeatedly during production for the smallest of defects.

As a sock nears the final steps of its life in the mill, it goes to a dedicated inspection team. By now, many socks have already been checked and handled by other employees, but additional scrutiny is crucial for Darn Tough’s high standards. “We find yarn-outs and mis-plaiting are most common,” says one checker. A yarn-out is what happens when a cone runs out of yarn, and the needle has nothing to put into the sock.

Cabot and the rest of the team are so sure of their product that they put their money where their mouth is — (or perhaps, more fittingly, where their feet are). One of the hallmarks of a Darn Tough sock is that it’s guaranteed for life, no questions asked. It’s this warranty that makes the company’s premium socks worth their relatively high price tag: to buy a Darn Tough sock is to make a lifetime investment. Any defect is fair game. One notorious case brought back a sock that looked as if it had been bleached or left out too long to fade in the sun — in actuality; it had made a journey through the digestive system of a Golden Retriever.

That confidence comes directly from Cabot, and it’s exhibited by every employee at the mill in Northfield. It’s the type of pride that seems inherent to many of the Green Mountain State’s independent makers — whether it’s maple syrup, cheddar cheese or a premium sock. From an outsider’s point of view, it’s a satisfaction that might mistakenly be viewed as brash when in reality it stems from a commitment to craft and product. Cabot isn’t afraid to tout the socks produced at his mill, but he’s also the first to acknowledge that perfection is never achieved: “We’re making the best product out there, and we’ve yet to make our best sock.”

The grill is the foundation of any outdoor gathering, but the requisite equipment for a proper cookout goes beyond the centerpiece cooking appliance. Read the Story