Viewed on a macro level, Sun Valley’s role in the history of the development of alpine skiing in the United States seems illogical. The region’s central town, Ketchum, is far from the urban centers on either coast; it was at one time a hub for mining, smelting, and the raising of sheep. But zoom in, and the squashing and tightening of topographical lines leave the point moot: the region was made for winter sport.

Once the Union Pacific Railroad — chaired by W. Averell Harriman, an avid skier — made the area more accessible to passengers, skiing developed quickly. The first chairlifts in the world were constructed on Proctor and Dollar Mountains in 1936, and they established Sun Valley as a resort destination for skiing. But many of the mountains visible on maps remained inaccessible to skiers until Sun Valley Heli Ski was founded by Bill Janss in 1966. It was the first heli-ski operation in the country.

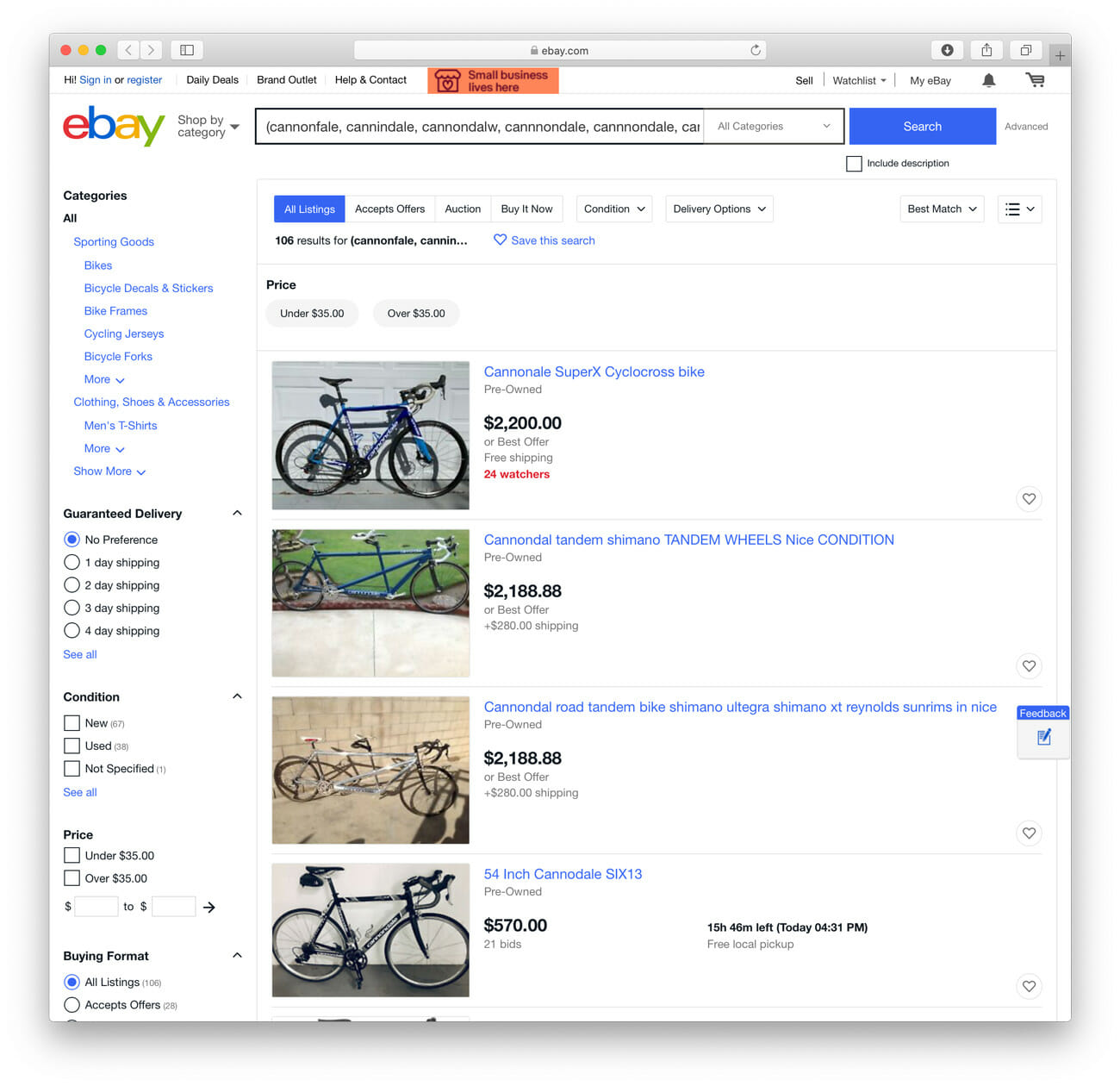

The main reason to integrate helicopters into skiing is access, and SVHS has loads of it. The team has access to roughly 750,000 square miles of terrain through a special use permit granted by the U.S. Forest Service. It’s one of the largest heli-ski permits in North America, and SVHS has the exclusive rights to it; to access many of the countless three thousand foot (and longer) runs without a helicopter requires multiple days of walking.

There is no ski patrol in the backcountry, so it’s up to the guides at SVHS to continuously monitor and control the risk of avalanches. But the guides don’t begin their day by flying missions and dropping TNT from the chopper to trigger avalanches — they’re in the office every morning at roughly 5 a.m. The flip of a light switch illuminates the base: the walls are lined with detailed maps, shelves are filled with avalanche gear and radios, a large monitor sits above a conference table. For the longest-operating heli-ski organization in the country, technology plays a central role, and the day begins in front of a computer screen.

“We get a really good idea of what our weather forecast is going to be for the day and whether we’re going to have a flyable forecast.”

“The first thing we’re diving into is the National Weather Service, which gives us a very direct forecast for our area,” says Alex Kittrell, a guide at SVHS. “We’re looking at cloud cover, precip type, our temps for the day, our wind forecast, a quantified precipitation forecast — how much snow they’re expecting us to get with temperature and moisture content — and a precip possibility. We get a really good idea of what our weather forecast is going to be for the day and whether we’re going to have a flyable forecast.”

That weather data is combined with detailed avalanche information to create a plan of action for the day. But unlike meteorological information, the data required to create a substantial avalanche report can’t be gathered through satellites and weather stations; it has to be observed on the ground, and that presents a significant hurdle for a guide service with as much terrain as SVHS. The solution, again, lies in a complex network supported by computers and technology.

“We have an incredible amount of snow data systems that we can gather data from,” says Pat Deal, SVHS guide. Most of that data is cataloged by the Sawtooth Avalanche Center and other organizations and is readily available online. Weather concerns — especially precipitation, temperature and wind — do play an important role in creating an avy report. “Wind is available to move an incredible amount of snow. Typically our biggest hazards out there are wind-related issues, wind slabs,” Deal says.

But the other half of that comes from direct observations, which the guides are recording every time they enter the backcountry. “Our snowpacks change every single day. We get pretty detailed when we’re digging in the snow, observing our different layers, and going through and doing our stability tests,” says Deal. But differences between snowpacks exist on a micro level. According to Deal, “Each zone has incredibly different snowpacks and the snow is different on every side of the compass.” So how does any guide service gather enough information to create a sufficient avalanche report? Through crowdsourcing.

“The snow is different on every side of the compass.”

At the end of every day, when the helicopter rotors are cooling down, the guides head back to the office to fill out a form called professional observations. “[The form] talks about where we skied for the day, what kind of stability or instability we saw out in the field, how many natural avalanches did we see, did we have any intentionally skier-triggered or unintentional skier-triggered avalanches,” and more, according to Deal. And SVHS isn’t the only group contributing this information. The Sawtooth Avalanche Center, Sun Valley Trekking and Sun Valley Mountain Guides also submit their own reports at the end of the day, which creates a comprehensive report for most of the area. The form is detailed and includes a place for comments and photos. One guide even managed to photograph an avalanche that was triggered by a mountain goat, just seconds after it occurred.

The guides at SVHS combine all this data into their own weather report. From there they use another piece of technology, Google Earth, to look at their range and either open or close runs for the day. The program allows the team to see the mountains in 3D, which adds tangibility to the mountain of data they go through each morning.

In the ’60s, when Sun Valley Heli Ski was founded, none of these systems existed. They didn’t have satellite phones, they didn’t have radios. The operation was kept much closer to town, and the team used topographical maps to scout potential ski runs. Carl Rixon, a previous owner of the company, used to fly a 185 Cessna airplane over the area searching for runs. “Nobody really knew what was going on in snowpack forecasting or why avalanches happened,” Deal says. Now, thanks to an online network that’s constantly becoming more and more sophisticated, backcountry operators can continue to explore all the terrain on their maps, and most importantly, be safe doing it.

Hard coolers don’t come much tougher than the YETI Tundra 65. It keeps contents colder for longer with up to 3 inches of PermaFrost Insulation and a ColdLock Gasket. The legendary toughness comes from the Rotomolded Construction that makes it armored to the core and nearly indestructible. For big days out or big parties at home during the holidays, the Tundra 65 has enough room to get the job done. Learn more here.