It’s a brisk 18ºF on a late-January morning, and Ted King is riding his fat bike down a snow-covered country road, tapping away steadily, but without great urgency. Over one shoulder, dark clouds crowd the horizon, and snow falls on some nearby hills. Over the other, a New England landscape so bucolic — barns dot the hillsides, a brook meanders through a pasture, and snow clings to every tree branch — it could’ve been ripped from a Currier & Ives print (all that’s missing are some merry-makers in a horse-drawn sleigh). Directly behind him, out of breath and lagging hopelessly, is me.

While this kind of Arctic-grade sortie has become almost routine for the former WorldTour pro cyclist, it’s foreign to me. And that’s why I’m here. Earlier this winter, right around the time my Strava feed was getting crowded by the avatars of fairweather cyclists riding through digital Watopian volcanoes on indoor bike trainers — I call them Zwift Weenies, and I’m one of them — King quickly stood out for doing exactly the opposite. Rather than holing himself up in a sweaty indoor pain cave and pretending he was somewhere awesome, he was outside, exploring in his own backyard. He posted 80-mile roadie epics, hard-charging fat bike hill climbs, and multi-sport adventures that combine bikes and skis — all of them against the frozen backdrop of Vermont’s wintertime snowscape.

I was impressed, of course, but also a little surprised. Though a born-and-bred New Englander, King hadn’t endured an honest-to-god winter for more than a dozen years. After graduating nearby from Middlebury College in 2005, he joined the professional peloton, working his way up from the UCI Continental circuit to the UCI WorldTour, where he competed in races like the Tour de France and Giro d’Italia. Back then, King spent winters between races chasing sunny, cycling-friendly weather in places like California and Girona, Spain. After retiring in late 2015, he moved to San Francisco, where he parlayed his charismatic personality and cycling celebrity into a full-time career as an ambassador for the sport, competing in high-profile amateur races and working with longtime sponsors like Cannondale and POC to get people stoked about riding bikes. It was only last September that King and his wife, Laura, bought a house in the town of Richmond, Vermont, population 4,140.

So how had he embraced the deep freeze of Vermont winters so thoroughly and so quickly? And why was he riding a bike in it? When I reached out to him for answers, he invited me to join him on a ride.

When I arrive at King’s house — a sizeable Greek Revival farmhouse on 11 rambling acres with a backyard pond and a classic red barn just down the hill — it takes me a minute to recognize the usually baby-faced, clean-cut road cyclist. He’s transformed himself to look the part of a grizzled adventurer: scraggly beard, patchy mustache and wild, mussed-up hair.

King’s new look is just one sign that he might be turning over a new leaf. Not only is he learning to embrace the ups and downs of a New England winter, he explains, he’s also just days away from embarking on a days-long, self-supported fat bike expedition across northern Ontario’s icy, wind-blown tundra, called the James Bay Descent.

The James Bay Descent, he explains, is a 600-kilometer expedition down the western shore of Canada’s James Bay that was organized by a Canadian named Buck Miller, a former elite amateur cyclist and an old friend of King’s. He’s recruited a pair of hearty Canadians — former national team mountain biker Eric Batty, and four-time World’s Toughest Mudder Ryan Atkins — and King. Though a formidable cyclist whose legs and lungs represent a significant contribution to the team, King is, in a sense, the odd man out, the fresh-faced expedition novice who’s never before taken his adventures off-grid, nor experienced such punishing conditions. The ride will be his first self-supported, expedition-style adventure.

Miller chose the route: it runs from Attawapiskat First Nation over the frozen James Bay to Akamiski Island (part of Nunavut) and south across the sea ice to Moosonee (the halfway point) where they join up with an ice road south to Smooth Rock Falls, their destination on the Trans-Canada Highway.

“Man, I wish it was single-digit temps out,” King cracks, zipping up his jacket as we prepare to ride. Novice or not, I think to myself, he’s champing at the bit. It’s not single-digits outside, but the wind is howling, snow is blowing across the road and King is decked out for an Arctic expedition.

After a few miles, we arrive at the end of Johnnie Brook Road and the base of 925-foot-tall Chamberlain Hill, where local nonprofit Richmond Mountain Trails maintains groomed fat bike trails. King leads the way into the woods, riding along a ribbon of freshly groomed singletrack that weaves its way sinuously through groves of hardwood and evergreen. It’s soon evident that, once again, I won’t be keeping pace with him. As we switchback our way up the hill, he easily pulls away from me, his hi-viz blue Velocio jacket darting in and out of view between trees and behind gullies where small, half-frozen streams trickle down the hill.

When I finally catch up to King, I’m sweating profusely under my layers. Maybe that’s the key to staying warm while biking in winter — trying to keep pace with a former pro cyclist. He’s dismounted and stands peering into a small wooden box that’s nailed to a tree trunk at the crown of the hill. He rifles through his overstuffed pockets, unloading handfuls of UnTapped waffles and maple syrup pouches — King is a co-owner of the company — and carefully stacking them inside the box, a food cache for hungry cyclists and Nordic skiers. Inside, locals have stashed a small bottle of whiskey, a jar of M&Ms, a jar of dog treats. And, of course, there’s a store of UnTapped goodies that King maintains. “I like to keep it stocked,” King says matter-of-factly, offering me a slug of whiskey. “Will it keep me nice and toasty for the ride home?” I ask, now that the chill is creeping back into my sweat-soaked clothes. “Nah,” he says, thinking better of it, “We should probably just head back.” And I think he’s right. After all, we’re about to head downhill — and fast.

Q&A

After the ride, over hot coffee and UnTapped waffles, King discussed living in Vermont and preparing for a cold-weather ride.

Vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas molesti Photo by John Doe.

Q: What do you love about living in Vermont?

A: The access to the outdoors is incredible, and that’s really surprised us. The trails that you saw today are a fraction of what we have. Skiing is super close by — 10 to 20 minutes, depending on what you’re looking for. There’s also a tight-knit New England community that I don’t think other places have. Sure, there’s great community in places like California and Colorado, but I think there’s some special sauce here that makes people particularly tight-knit.

Q: Are the less-than-ideal riding conditions aren’t impacting your fitness?

A: Vermont is an adventure, and I’m embracing it for what it is, rather than spiting it as not a great place to train. I think it’s perfect. Every day doesn’t have to be an epic bike ride. Some days, I’ll go AT skiing — skin up, ski down — or work on my Nordic skiing technique, and I might combine that with a fat bike ride or, if conditions permit, something on the road.

Q: What challenges does your first self-supported, multi-day expedition pose for you?

A: There are many elements I’m familiar with — like riding long distances, and being able to endure, both physically and mentally. I know how to suffer; I know how to get into a routine and push through adversity. The self-supported multi-day aspect is new to me. I’ve really embraced the term “team.” We’re a team, and everybody has each other’s back, and there’s a great deal of trust that goes on given that the elements can be so fierce.

I think there’s something cool about the prospect of being so outside of your traditional element. I make the comparison to bike racing all the time, which is such a controlled environment — there’s a start line, there’s a finish line, and you have an entire team of people around you to take care of you. This has so many more variables that you’d never see in bike racing, or in traditional life. It’s sort of nice to be on your back foot and to be put into an environment that isn’t necessarily your normal comfort level.

Q: What have you been doing to prepare mentally and physically?

A: I’m spending a lot of time in cold weather. Moving to Vermont was helpful, but this is a fraction of what we’ll be getting up there. I’ve been riding the fat bike quite a bit. Two weeks ago, the four of us did a sort of acclimatization trip in the Adirondack Mountains. After prepping gear, installing racks, and making sure everything was in working order, we rode to the top of Whiteface Mountain via its access road. It was absolutely stunning; the sunset was just out of this world. Then we camped out in -1ºF temperatures, which was eye-opening and helpful for understanding what exposure is and what camping in subzero temperatures is like. That was a gnarly, icy descent.

Q: What’s the team’s strategy?

A: Plan for the worst, hope for the best. Seriously, though, we’re trying to keep our stopping to a bare minimum. I think it’s largely exposed, with very low trees; head-height or lower for the most part. It’ll be very flat, and very windy. We’ll try to ride slow enough that we’re not sweating, but fast enough that we stay warm. It’s a funny balance like that.

Vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas molesti Photo by John Doe.

Q: How does nutrition factor in?

A: It’s simple: eat a lot and when you’re hungry. We don’t want to stop to eat, so we’ll just always be eating something, and that’s where UnTapped will be huge to fuel our days in the saddle. Then we’ll make hot meals, mostly freeze-dried camp food, on either end of the day when we have the benefit of hot water.

Q: Do you think this trip will change your relationship with cycling at all, or that it represents a shift?

A: I think it will. Everything within cycling is so controlled, and I think it’s safe to say that’s true of the world in general, too. We try to control our environments, and have a schedule, and like to feel very safe in this little nest of our lives. This is going to be the gnarliest set of elements I’ve ever experienced. From a weather perspective we’re looking at as low as -40ºF, and even colder when the wind is blowing (and I’m told it almost always does). And certainly, the risks are higher than in normal life. It’s very real out there. I’m not doing it to look for a transformative experience; I’m doing it to step out of my comfort zone, to do something totally different from what I’ve ever done before. [Long distance gravel races] are adventure-y, but this is adventure. Full stop.

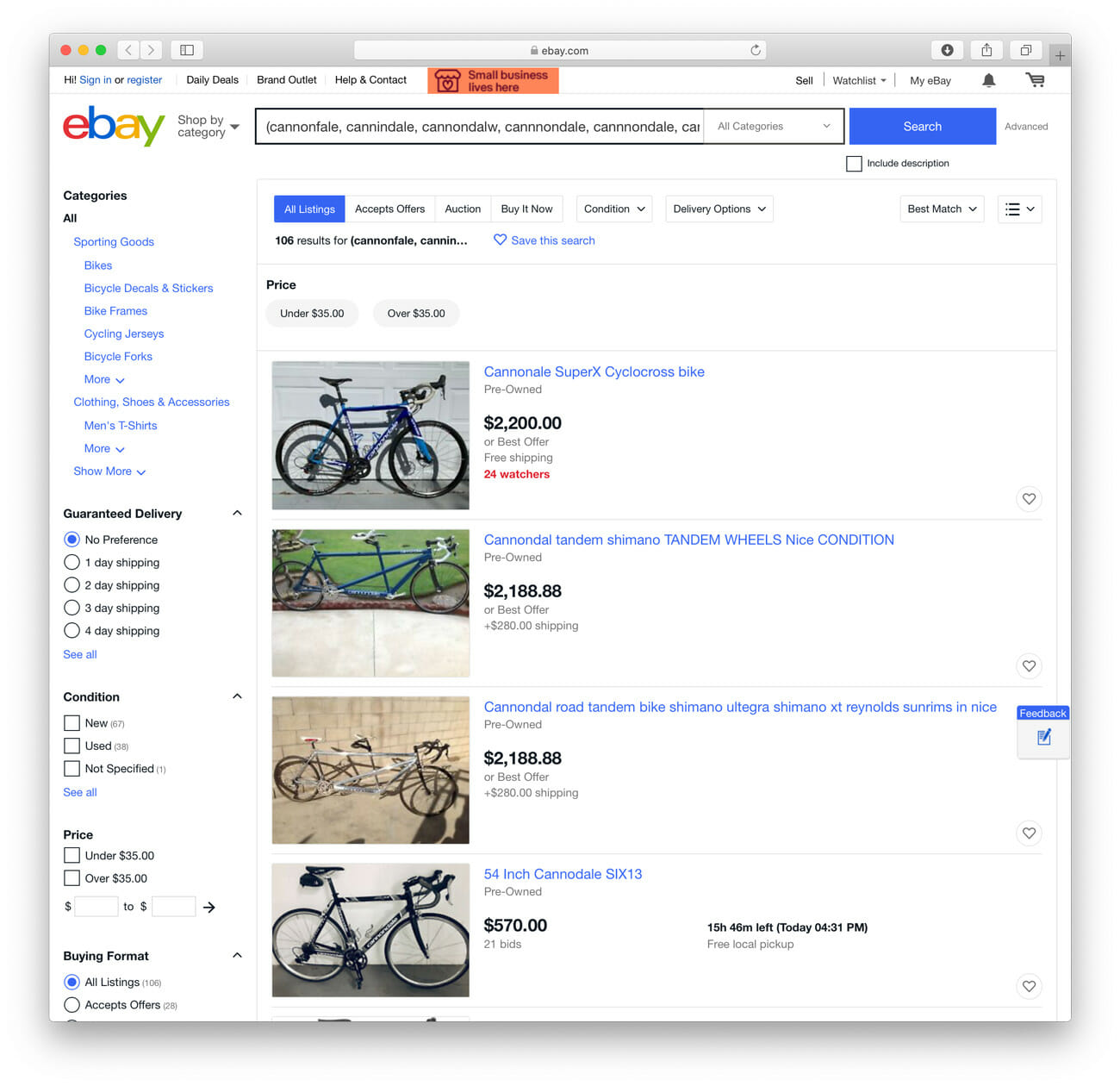

Ted King’s Winter Cycling Gear Picks

Cannondale Fat CAAD 1

“A winter shred sled! This bike is a dreamboat. Already plush with 4-inch fat tires, the Lefty Olaf front suspension makes this bike a blast to ride.”

Velocio Zero HL Jacket

“Hi-vis with warmth where you need it, plus all the virtues of a great cycling upper, like three generous rear pockets, and three front pockets (two side and one on the chest) to store all sorts of winter accessories.”

45NRTH CobraFist Pogies

“These function like a second, super-warm, super-burly set of gloves and, frankly, are the only way I’ve found I can keep my hands warm in the winter. You can throw chemical hand-warmers in there when temps bottom out at -40ºF, but, otherwise, you rarely need more than a thin pair of gloves underneath. For warmer days, there are ventilation zippers on the top and bottom.”

45NRTH Ragnarök Boots

“From brisk winter commutes to four-hour winter sessions, the Ragnaröks are fast on, fast off, and just a fast set of winter boots.”

Blackburn Outpost Elite Frame Bag

“On the James Bay Descent, I kept my daily, easy-grab food in the side pouches; my tools, spare tubes and valves in the zippered compartment down below; and my frame pump and more food in the top compartment. What I love about this thing is you’ve got everything you need close at hand, it’s protected from the elements by the waterproof, welded material, and it’s tucked away in the front triangle, lowering your center of gravity and keeping your ride nice and stable.”

Fischer Carbonlite Skate H-Plus Skis and Carbonlite Skate Boots

“I’m a capable enough Nordic skier to know that I’m a very novice Nordic skier. When I first got to Vermont as a freshman at Middlebury in 2001, I bought a set of Nordic skis and boots—the whole nine yards. Now, nearly 20 years later, with the benefit of better technology, plus being on a top-of-the-line system with the Carbonlite skis and boots, I feel like I’m going from a tractor to a Ferrari. The boots are incredibly stiff, yet super comfortable. Whereas the previous boots had the strength of a sock, these boots deliver an enormous amount of power to the skis, similar to how a carbon-sole cycling shoe better transfers power to the pedals.”

|

Fischer Ranger 108 Ti skis and Ranger Free Boots

“My Fischer Ranger AT set up is a blast. I’ve never had such a comfortable set of ski boots as I do with these. The skis are light, yet medium-fat underfoot — ideal for a fresh Vermont day, or even running them inbounds for optimal East Coast skiing.”

|

CycleOps H2 Smart Trainer

“I’m riding the H2 Smart Trainer by CycleOps. I often pair it up with TrainerRoad ($15/month), which allows me to create custom rides with all the intervals I want to do (or not). Riding outdoors is my preference, but when I need a very specific workout, this duo is how I get those rides in.”