W

ay back, at my fitness nadir, a sales guy at a specialty running store told me I should wear Asics. I was new to jogging, new to exercise for its own sake, and consequently had just finished college three pant-sizes above my ideal. After watching me clomp up-and-down the sidewalk a few times, the guy diagnosed me as a chronic over-pronator (I recall a somber, analytic air, like what you might encounter in an oncologist’s office) meaning that I rolled my feet inward as they left the ground. Over time, he said, this would lead to knee, ankle and hip pain, or debilitating mash-ups of all three, so I needed running shoes with mid-sole stability and liberal cushioning. Other phrases stuck, mostly for their odd eroticism: “moderate torsion rigidity,” “energy return,” and “neutral ride.” Fortunately, he grinned, all of my needs came neatly bundled in one pricey, state-of-the-art, Day-Glo pair of Asics.

I’ve since poured half a lifetime of faith and currency into Asics’s over-pronation correctives. Now, as I plod into my 40s, my body dwindles and recedes, its abiding pangs tripling monthly, it seems, as everything from the hips down creaks like corroded machinery. Iliotibialis. Patellofemoral region. Soleus. These things suddenly mean something to me, as all radiate pain. It’s in preparation for the grave that I’ve tried to resign myself to this, my mind on a vigilant appendicular death watch.

Like every running shoe company, Asics has gone deep into the curative design realms. The order of magnitude here is difficult to overstate. Injury-prevention metrics of pronation (over and under) and impact force (sometimes called “foot strike,” ameliorated by cushioning or lack thereof) are the industry’s theoretical guiding lights, against which all else is measured. In service to them, no amount of garbled techno-jargon and morbid joy has been spared. Asics’s GEL-Kayano running shoe, for instance, aimed at over-pronators like me, employs the company’s proprietary “FluidFit system,” which promises “biomechanical efficiency” through a unique “dynamic taping” matrix and “external heel clutching system” and “gender specific cushioning,” allowing “mild and moderate over-pronators” more “safety control” and “a more luxurious and longer run.” Fair enough. But does it work?

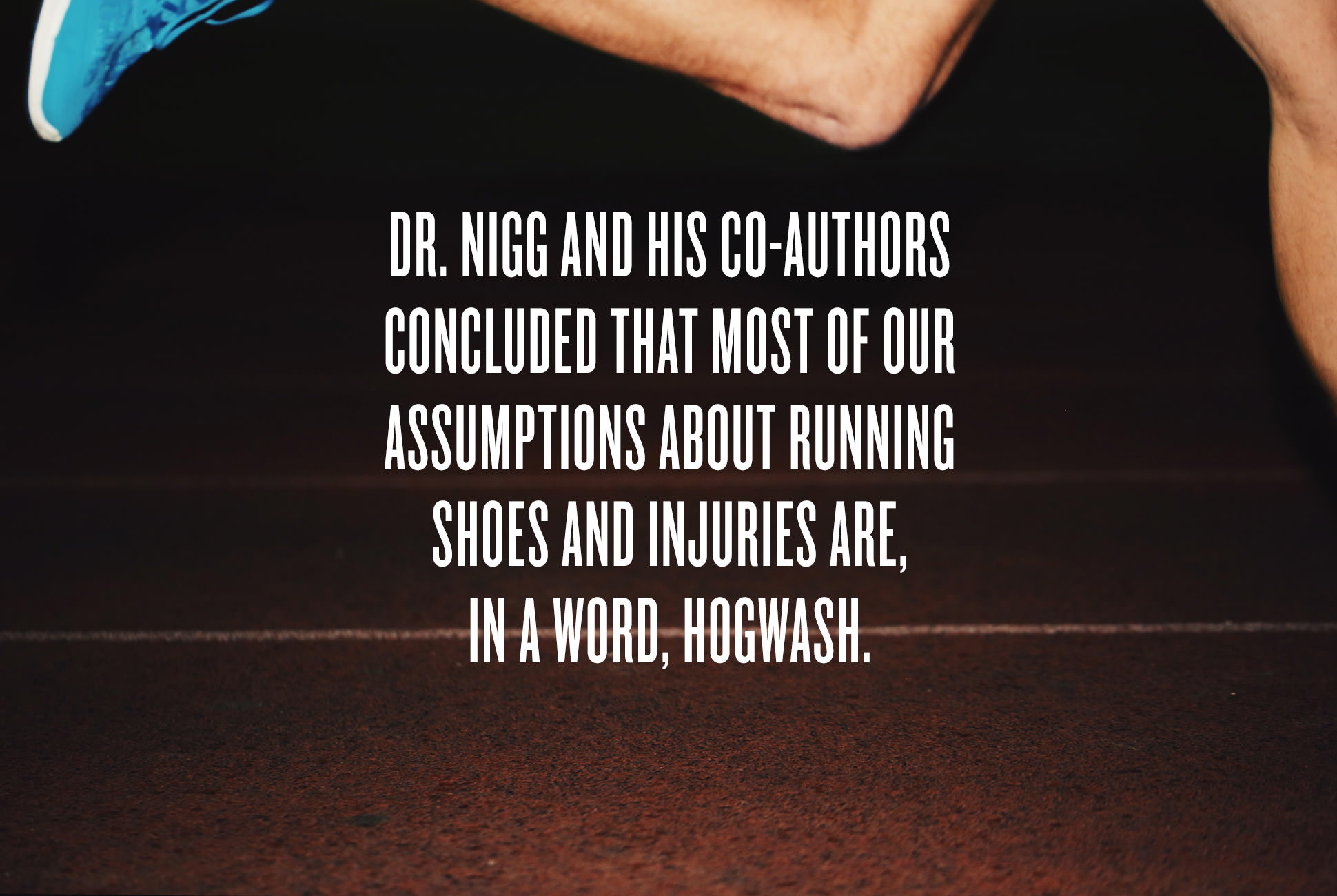

“We’ve talked about this for thirty years,” Joseph Hamill, professor of kinesiology and head of the Biomechanics Laboratory at UMass-Amherst, told me. “The fact is, foot pronation or impact force have never been conclusively linked with any kind of running injury, or even the prediction of injury.” Hamill and I were discussing a recent review in The British Journal of Sports Medicine by a biomechanics expert named Benno M. Nigg. After digging through 40 years of research, Dr. Nigg and his co-authors concluded that most of our assumptions about running shoes and injuries are, in a word, hogwash. Pronation, it turns out, isn’t a problem that requires correction or benefits from attempts to correct it via shoe design. And there is almost no evidence that impact force causes injury, or that changing or removing shoes (in the Vibram/barefoot vein) alters impact much at all.

To wit, everything we think we know about running shoes is wrong: footwear designed to somehow “fix” your running form and prevent injury – that is, basically all running shoes – according to Hamill and Nigg, are at best ineffective, at worst counter-productive. Despite decades of research and costly advances in shoe design and materials, running injuries haven’t abated one lick; in fact, more than half of runners still get injured every year, a rate comparable to what it was 30 years ago.

How, then, did shoe companies drag us down the pronation/impact rabbit hole?

“If you go back thirty years to when researchers first started looking at injuries and footwear,” said Hamill, “there were an awful lot of knee injuries. We tried to make a link between things like internal and external rotation of the knee and how shoes might affect it. We thought there was a natural association there, and it became dogma.”

Which isn’t to say that shoes aren’t important vectors in running, or that barefoot running offers the surest path to righteousness, only that pronation and impact aren’t reliable measures for predicting injury, or for choosing the right shoes. (To be sure, some researchers aren’t convinced. David J. Pearsall, a professor of biomechanics at McGill University, thinks pronation and impact are still obvious measures for injury. “We shouldn’t totally discard them,” he said. “A lot of running injuries are chronic and happen over a long period of time, while others happen from running too quickly or too hard over a short period of time. The point is, they’re difficult to measure. So, to ignore pronation and impact seems to me to be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”)

When it comes to choosing the right shoes, Hamill and Nigg suggest following the most scientifically sound criteria we have: comfort.

“Choose a shoe that feels good,” Hamill said. Simply put, in the most comfortable pair of running shoes, you’ll run more efficiently and suffer fewer injuries.

Comfort, of course, is the stickiest of wickets. It’s different for everyone, and changes with body type, muscle strength/weakness, speed, stride, fatigue, previous injury, terrain, climate, age, attitude, etc., in short, a kaleidoscope of variables that spins on an enigmatic axis.

“Comfort is a very personal feeling that gets down to the psychology of running,” Hamill said. “Basically, you want to feel relaxed, snug.” This generally translates into a cozy foot-bed and upper, with no chafing or pinching anywhere. You also don’t want to feel like you’re fighting a shoe, Hamill said, which can mean it’s altering your natural gait. And you want a wide range of motion – a shoe that isn’t too loose or too tight, and that lets you run as your body is meant to run.

With this in mind, and in the throes of ancient ankle grief – a pain that surged and swirled from Achilles to malleolus to subtalar and back again – I tried a dozen pairs of running shoes over the course of four months, excepting Asics (too much baggage): Adidas Supernova Sequence Boost 8, Newton Gravity, Reebok ZPump Fusion and ONE Cushion 3.0, New Balance 1500v1, Mizuno Wave Rider 19 and Wave Inspire 12, Brooks Glycerin 13 and Launch 2, The North Face TRII, and Puma’s Speed 600 Ignite and Ignite Ultimate (there’s an obvious joke here about shoe names and NASA suborbital space flight). All were chosen purely based on comfort.

I ignored specific design parameters – for instance, Brooks’ technology employs what the company calls its “Stride Signature,” which is a correlation of Nigg’s concept of “Preferred Motion Paths,” which, in a nut, is the same thing as Hamill’s comfort matrix: that is, a shoe that allows you to run the way you’re body wants to run, that doesn’t change your natural gait. But I liked them simply because they felt good. In fact, comfort with every pair mentioned above was through the roof. After two months, with mileage and terrain roughly commensurate, my ankle pain lessened, then gradual ebbed to nominal, until it wasn’t pain at all anymore, but like a memory from an old war.

As far as I’m able to choose favorites – and this is as tough as it is laughably unscientific, since my comfort gauge was to wear each pair for about a week-and-a-half of jogging – Mizuno’s Wave Rider 19 and Brooks’s Glycerin 13 both had some unmeasured quality, gracefulness I suppose, or luxury, but luxury in a burly, workaday sense of the word and not in the flannel pajamas sense. They transmuted my unsightly, feral, windmill gait, bolstered my natural patterns, and excavated a long-dormant trust in being competently shod. In both I just felt, I don’t know, better. So much better that, switching between the two pairs, I ratcheted up my speed and mileage considerably, even dropped a few pounds.

It’s worth remembering that injury is inevitable. Bodies break down. That’s what they do. No shoe is going to stop that. I’m 42. At a certain age, the best of us is in the past. “To grow old is to lose everything,” Donald Hall writes. “Aging, everybody knows it.” Minimizing your injuries before death takes it all requires not just self-knowledge – awareness of your limitations and heeding them – but a kind of brute honesty that most of us are plainly terrible at. We think we’ll live forever so we obscure our experiences, try again to conquer Denali in flip-flops and bicycle shorts. We hurl ourselves toward the void, invoking various gods.

I kept on running, flying along the Charles River path in Cambridge, lapping the Harvard cross-country team, shouting into the wind. Then one day my knees gave out. It was a double-tweak, swift and terrible, and snuck up on me, like a lead pipe to the back of the knees, and probably had as much to do with lugging my twenty-pound daughter around all day as it did with notching up my mileage/intensity ratio. My doctor told me not to worry, that the pain will likely vanish once my daughter learns to walk. But today my knees are ruins, throbbing and buried in ice. I write this from bed.