In the grand Porsche tradition, the 2018 Porsche 911 GT3 is iterative rather than revolutionary, but that doesn’t mean the engineers were content with simply upping the power and adding a bigger wing. (They did both, by the way, but much more than that.) Sure, the engine displaces 4.0 liters and makes 500 horsepower, just like the GT3 RS. But understanding exactly where and how the 2018 GT3’s engine has been re-engineered is crucial to understanding this car in its entirety.

That’s why we’re taking a moment to delve into the nifty tidbits and oily underbelly of this car. First Drive impressions are coming, but this is a treat for the true believers.

Some background on this engine. It’s related to the 3.8- and 4.0-liter engines used in the previous 911 GT3, the 911 R, and the 911 GT3 RS. But it differs in some important ways from the units used in those cars. For one, the engine compression has been increased to 13.3:1, compared to 12.9:1 in the other three. Porsche spent a lot of time identifying and combating friction in the internals as well as the ancillary components, basically scavenging otherwise “lost” power without needing to punch out the engine even larger.

Remember, the old GT3’s 3.8-liter displacement represented the most Porsche could expand the bore, so the step up to 4.0 liters required stroking. Once at that displacement, there are no “easy” ways to suss out extra power from this mill, so Porsche did what it does best: optimizing everything possible without sending costs out of control – for example, using a steel muffler instead of the GT3 RS’s titanium unit. The result is a gain of 25 horsepower and about 15 pound-feet of torque compared to the previous GT3, and matching the GT3 RS – although the power curve is different. More on that later.

In between laps at a little circuit in Spain, I noticed Andreas Preuninger, the guy in charge of the entire GT program, standing over by a static engine display alongside the track and got him going on what makes the engine tick. We started with the solid lifters, which replace the hydraulic ones in the last GT3. The change allows Porsche to use softer valve springs, which reduce friction (and therefore horsepower loss) in the valvetrain. I’m told the lifters don’t need adjustment over the engine’s lifetime, and that the system is derived from Porsche’s racing experience. After all, the 911 RSR uses the same “rigid valve drive” concept, to use Porsche’s lingo. Preuninger looks like he’s geeking out about this, which is undoubtedly true.

Lots of neat details on the #911gt3 4-liter engine. Exhaust mount w/ speed holes and webbing on the exhaust valve flange. @therealautoblog pic.twitter.com/gwJg7Dsns7

— Alex Kierstein (@HanSolex) April 26, 2017

I can’t help but ask him about the revised redline – how the GT3 beats the GT3 RS by 200 RPM, and the 911 R by 500 RPM, without sacrificing something else. It turns out I’m asking the wrong question. The GT3 RS made its peak power at 8,100 RPM, after which power fell off sharply, so there was really no reason to rev much beyond that. As for the 911 R, Porsche had to take its manual transmission (and probable buyers) into account, so Preuninger’s team reduced the redline so that there was some cushion for accidental mechanical overrevving.

The new GT3’s power peak is 150 RPM later than the GT3 RS, and the power curve is flatter, hence the GT3’s higher redline. While Preuninger didn’t say so explicitly, he gave me the distinct impression that the sort of customer attracted to the GT3 – one with loads of on-track experience who is making a conscious choice to buy the slower manual transmission version – probably knows what they’re doing and won’t blow a shift (and the motor).

A few other internal choices were made to not only benefit this car, but to help out the Motorsports division. For one, the engine’s reengineered crankshaft allows the engine to rev to that 9,000 RPM limit, as well as provide improved lubrication to the main bearings, and it’s identical to what the Motorsport guys use in their race engines. Thanks to the magic of economy of scale, this makes what was once a very expensive part cheaper. Likewise, there’s a new oil pump design with a built-in centrifuge, which defoams the oil. Foamy oil reduces critical lubrication efficiency, and the design comes straight from the company’s decades of experience gained in racing.

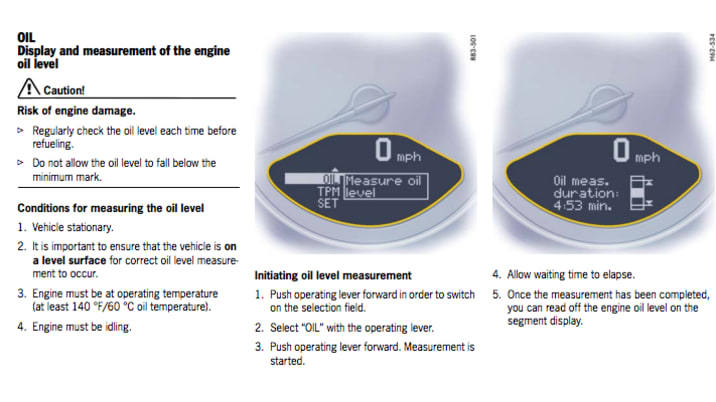

Speaking of oil, Preuninger heard a lot of complaints about the long and fussy oil level check procedure, which often takes upwards of three minutes (provided the car is on level ground, idling, and at operating temperature – see below for a shot from the contemporary car’s owner’s manual). He was quite proud to have addressed that particular complaint, reducing the time and hopefully saving himself from catching grief the next time he’s at a PCNA event.

I decided to see if I could pull an interesting tidbit out of something mundane. I noticed the oil-to-water intercooler nestled next to the oil pan, and mentioned that it looks a lot like a plate chiller used in making beer. Of course, even that elicited an Preuninger anecdote. The cooler is modular, so stacking more plates means more overall cooling capacity. But the Motorsport GT3s run two plates fewer than the street car. These plates are thin, no more than a few millimeters, but the slight increase in ground clearance is more important than some fractional improvement in oil cooling.

The engineering rabbit hole goes much deeper than this, but suddenly it was my turn to take the GT3 out on the track. Even so, what Preuninger told me shows why simply calling this a “revised GT3 RS engine” doesn’t quite do it justice.

There’s a savvy reason why Preuninger is happy to nerd out about all these things, and that’s because GT3 customers are exactly the same way. Apparently they’re fond of reading the entire owner’s manual cover-to-cover right after taking delivery, poring over every detail and then peppering Porsche reps at events like Rennsport Reunion with questions the Porsche guys have trouble answering on the spot. They are Preuninger’s people, and this is their kind of car.

Related Video: