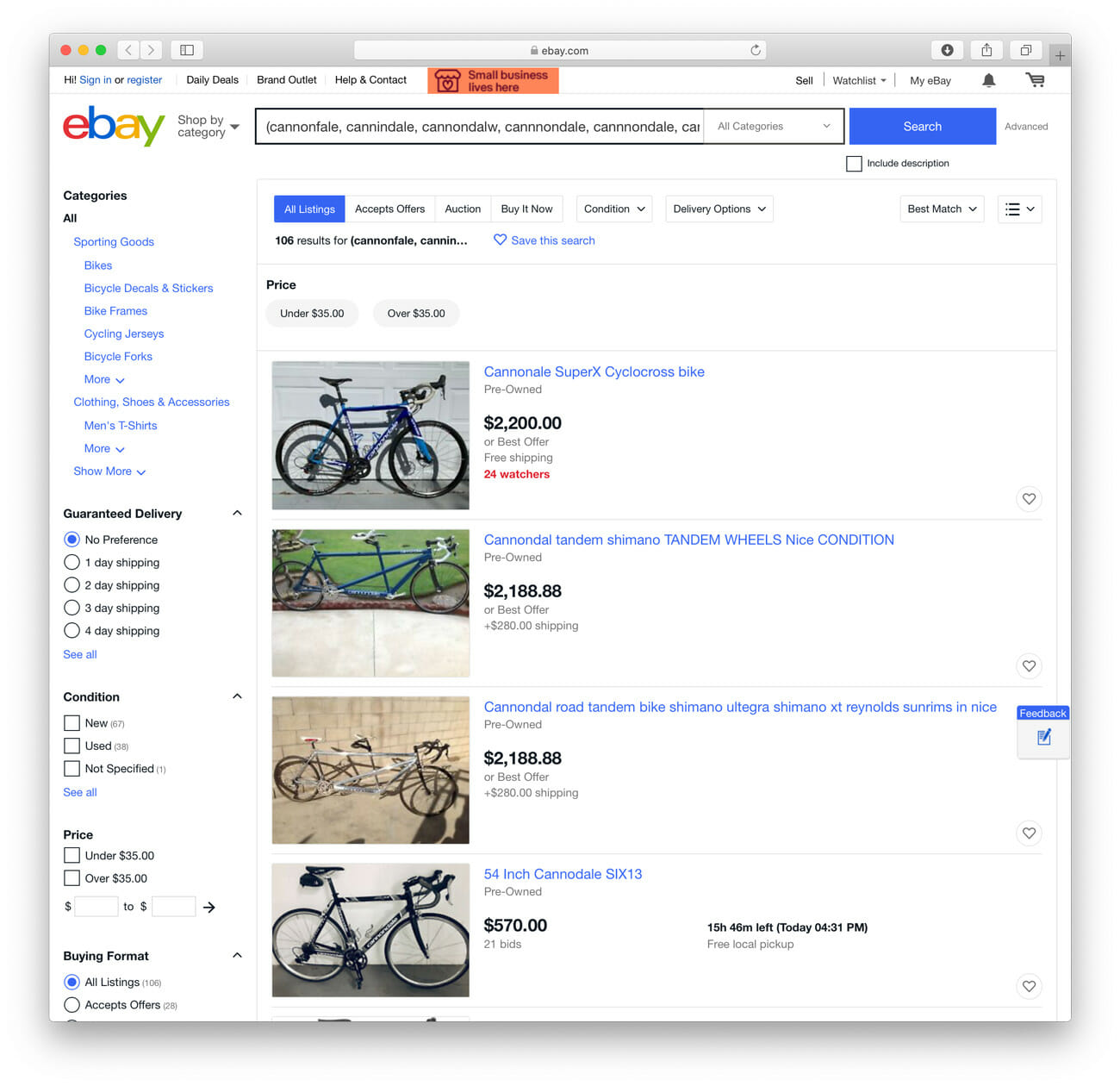

A version of this story appears in Gear Patrol Magazine. Subscribe now.

On March 10, 1953, an army of nearly 400 men left Kathmandu, Nepal, and set out to conquer the highest peak on Earth. There were 13 mountaineers from Britain and New Zealand, 362 porters and 20 Sherpas from Nepal, together carrying over 10,000 pounds of gear. By then, the summit of Mount Everest had eluded 11 previous expeditions. Dozens of men had been killed. But this time would be different. Eleven weeks after leaving Kathmandu, two unlikely companions — a beekeeper from New Zealand named Edmund Hillary and a Sherpa from Nepal named Tenzing Norgay — stepped onto a small, wind-blasted, heavenly lit altar made of snow and rock and became the first men in history to summit Everest.

It was a triumph of the human spirit. Hillary and Norgay became overnight legends, and mountaineering was changed forever. But what of the things they carried with them? The men wore 44-pound backpacks, bodysuits made of cotton and down, windproof smocks, nylon trousers, waterproof boots, silk gloves, heavy oxygen tanks and wool base layers and carried ice axes made of wood and steel. At the summit, Norgay placed chocolates as an offering to his gods; Hillary buried a small crucifix as an offering to his. They may have reached the highest point on Earth by their own sheer will, but without gear — the items that kept them alive, and the items that gave them purpose — the summit would have been impossible.

The legacy of legends like Hillary and Norgay continues today in the greatest living mountaineers. They still embark on epic pilgrimages to the world’s highest, holiest, most challenging peaks; they still rely on gear to reach the summit, and to return intact. And all mountaineers know of a profound mystery: When a simple thing, be it a pair of glacier goggles, a watch or a bag of blessed rice, ascends a mountain, it transcends the material realm; it becomes a piece of history, an outward manifestation of the mountaineer’s spirit, a holy relic. And every relic tells a story.

Conrad Anker

Broken Portaledge Pole

It was our third night on Meru. We were probably two or three pitches below the big headwall, halfway up the 14,977-foot-high mountain — right below the Shark’s Fin itself. We had crossed the Rubicon. That night, we pitched our portaledge, a single-point suspension cliff dwelling with an aluminum frame. In the morning, my climbing partner Renan Ozturk was sitting right on the edge of the tube when it bent, then snapped. Our stuff went flying out — my down pants, luckily, got hung up on a spike of rock about forty feet below. I would’ve been fucked if I didn’t have those. Before the ‘ledge snapped, I would sleep with just a piece of rope tied around my belly. After the ‘ledge snapped, I started sleeping in my harness.

Renan and Jimmy [Chin] got onto the cliff with their senders, and I went down and got my insulated pants, came back up, put the portaledge back into its haul bag, and then we pressed on. That night, we did some MacGyver repairs on it: a piton for an internal splice, two ice screws on the outside and some athletic tape. When I got back to Montana, I engraved “Meru 2007” on it and crimped some wire and an old piton onto it. Now it hangs in my garden.

I quite savor the exposure out there. Looking out of the ‘ledge, knowing that you’re imprisoned by gravity, but freed from gravity too. You’re sailing on a sea of granite.

Notable Achievements

• First ascent of the Shark’s Fin on Mount Meru, a Himalayan peak long thought to be impossible

• First ascent of Vinson Massif’s East Face and Rakekniven Peak’s Snow Petrel Wall in Antarctica

• El Capitan’s Continental Drift in Yosemite

• Latok II’s West Face and Spansar in Pakistan

• Three summits of Everest (one without supplemental oxygen)

• Captain of The North Face Athlete Team

Apa Sherpa

Julbo Glacier Goggles

In 2007, six of my family members, two friends and I climbed Everest. We called it the Super Sherpa expedition — between the eight of us, we had fifty-five Everest summits. I wore these Julbo glacier goggles on the expedition. They protected me from snow blindness, which I’ve had before. The Super Sherpa expedition was the first time an all-Sherpa team climbed Everest without working for Westerners.

Normally, Sherpas just help Westerners get to the summit; this time, we didn’t have to suffer for anybody. We didn’t have to carry their oxygen tanks. We didn’t have to carry their water, fix their ropes or set their tents. It felt like more of an adventure. When we’re working as Sherpas, we don’t really get to think about adventure. We’re just doing our job, helping Westerners realize their own adventure. But the Super Sherpa expedition was our adventure. It was a very proud moment in my life. On the summit, we all hugged, took a photo together and shouted with joy. It was my seventeenth ascent of Everest.

Notable Achievements

• Tied for most Everest ascents of any person in history (21 summits)

• Led the expedition of the 1,050-mile long Great Himalaya Trail (widely considered one of the world’s most difficult treks)

• Founder of the Apa Sherpa Foundation

Ed Viesturs

Rolex Explorer

Throughout my whole career I’ve been fixated on being punctual. I lived by one rule: if I wasn’t on or near a summit at two o’clock, I had to turn around. That gave me this margin of safety to make sure that I could get back down. I never broke that rule. I was always on the summit at two o’clock, or well before.

I remember looking at my watch as I was climbing Annapurna. We were still going up, and the clock was ticking, getting closer and closer to two o’clock. I remember we reached the summit at exactly two. I keep questioning myself on that particular climb, and on that particular day: had it taken us longer, would I have broken my rule? That’s what a lot of people do on the mountain; they have rules that they have lived by for a long time, and then there’s that one day they break their rule. And that kills people. You live by rules. You have protocols. It’s the one day you decide to take a shortcut or break or stretch a rule when accidents happen.

Notable Achievements

• One of 33 people in history (and the only American) to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks (the fifth to do so without supplemental oxygen)

• Seven ascents of Mt. Everest

• One summit of Kanchenjunga in Nepal (third highest peak in the world)

• One summit of K2

• One summit of Vinson Massif (highest peak in Antarctica)

• 208 summits of Mount Rainier in Washington

• Numerous alpine rescue missions; published author and motivational speaker

Jeff Lowe

Early prototype of Tricam climbing device

Time after time in my life, when things were going wrong, I found that doing a long, hard climb would set me straight. I’d come to the Eiger in the Swiss Alps in February 1991 because climbing is my joy, and I really needed some joy in my life then. I needed a way out of the chaos I’d made, and to make a new direction for myself. But at the same time, I was there to make art, if I could — to create something that had never been seen before.

I had read Heinrich Harrer’s book The White Spider when I was twelve. The epic of the first ascent of the North Face of the Eiger never left my mind. In February 1991, I wanted to climb the North Face in a style that honored its pioneers. Anderl Heckmair and company didn’t have bolts in 1938 — just simple pitons of a limited range. They risked not being able to start their crude stoves to melt water; if their cotton and wool clothing got soaked, they might freeze to death. To even approach that level of commitment, I had to stack the deck against myself: go alone, in winter, without bolts, and try the hardest unclimbed route I could find on the highest part of the wall. My intention was to make the purest climb I could manage.

These Tricams were a staple on my climbing rack for two decades and were with me on the Eiger. They were prototypes invented by my brother, Greg Lowe. He and our older brother, Mike, had been working on camming devices for climbing protection since 1967. They hold better than anything else in icy cracks. At one place on the Eiger, a Number 1 Tricam saved me from a much longer fall, where I could have been badly hurt.

I named the route “Metanoia” [for “a transformative change of heart”]. For thousands of years, shamans and other spiritual seekers have starved themselves, endured long days of toil and meditated for days and weeks in hopes of receiving some sort of vision or nirvana. On the Eiger, I’d felt my own fundamental change of thinking and of heart.

Notable Achievements

• Credited as the father of North American ice climbing and mixed climbing

• Highest point reached on the North Ridge of Latok 1, the Himalayan peak widely considered the world’s most difficult unfinished climb

• Over 1,000 first ascents, including the Grand Central Couloir on Mount Kitchener in the Canadian Rockies, solo first ascent of Ama Dablam in the Himalayas, and Metanoia, a solo direct route on the North Face of the Eiger in the Swiss Alps

• Featured in the award-winning biographical film Jeff Lowe’s Metanoia

• Recipient of the Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement, the highest award in alpinism

Climbers Adrian Ballinger and Cory Richards talk about the merits of climbing Everest without supplemental oxygen. Read the Story

Melissa Arnot

Prayer card and bag of rice blessed by a Buddhist monk

There’s an 89-year-old lama who blesses climbers in Nepal before they climb to the summit. His name is Lama Geshe. He gives you this card marked with a Buddhist prayer that wishes goodwill to all people in the world. Then, he blesses some rice, puts the rice and card inside an envelope and instructs you to throw the rice if you ever feel that danger is near.

In 2013, I was climbing through the Khumbu Icefall, a notoriously unpredictable and dangerous area on Everest. The wall of ice above us was probably forty feet tall. We were climbing up the wall on a ladder when the ice suddenly shifted. I thought we were going to die. My climbing partner had blessed rice, too, and I had rice flying in my face before I realized what was happening. After that, I started keeping a little handful of it in my jacket pocket.

Throwing rice is a funny thing for me, since I’m not superstitious at all. I’m an incredibly pragmatic realist. I believe everything happens as it should. And yet I’ve been carrying the rice and card with me nearly everywhere I go — all year long, on every peak I climb.

Inside the card I have a photograph of my climbing partner, Chhewang Nima, who died on a climb with me in 2010. He was a Nepali Sherpa, and a really close friend of mine. He was incredibly revered in the climbing community. Many believed that he was spiritually enlightened — he was going to be a lama. It was tragic for so many reasons when he died. I keep this photo of him on the summit of Everest inside the card. It feels like he’s with me — nestled in the mix of the blessings and rice seems like the right place for him.

Notable Achievements

• Second most successful female Everest climber in history (six ascents)

• First American woman to summit Everest without supplemental oxygen

• Three summits of Aconcagua in Argentina

• Five summits of Cotopaxi in Ecuador

• 92 summits of Mount Rainier in Washington

Jimmy Chin

Nikon film camera

It was 1999. I was training for my first big expedition to Pakistan. My friend and I were in Yosemite — we had just finished this climb on El Capitan called Native Son. We woke up the next morning on top of El Cap and there was really beautiful light, so I reached over, grabbed a camera and took a photo. My friend had been submitting photos to different companies, and he suggested that I submit mine. Mountain Hardwear actually bought my photo, published it and paid me for it. It was the first time I ever got paid for a photograph, and it was one of the first photos I ever took with a real camera.

I had the logic of a twenty-three-year-old climbing bum. I thought, “Wow! I only need to take one photo a month, and I could live like this forever out of the back of my baby-blue 1989 Subaru Loyale.” Months later, I met Conrad Anker, who then helped me land a deal with The North Face. It really wasn’t that exciting of a photo. It was a moment of dirtbag climbing-bum living. But it pretty much launched my career.

Notable Achievements

• World-renowned photographer and filmmaker

• First ascent of the Shark’s Fin on Mount Meru with teammates Conrad Anker and Renan Ozturk

• Three first ascents in the Karakoram Mountains

• One of a handful of people in history (and the first American) to ski down Everest

• 15 one-day ascents of El Capitan in Yosemite

• Director of the award-winning film Meru, which documented the historic Meru ascent

Renan Ozturk

The North Face alpine pants

When you’ve been to the top of a peak with something, it feels like a good luck charm. I’ve had these pants since 2010. They were designed, originally, for our second attempt of Meru. They’ve been on countless other expeditions– Burma, Alaska, Nepal, Chamonix, our backyard in Park City, Utah.

Taylor Rees, my wife, has done a lot of the handiwork and patching on them — we add about ten patches every year. I probably would’ve turned them away a long time ago if she hadn’t fixed them. But I just keep coming back to these old, ragged, patched-over pants because they fit me better than any pair I’ve ever worn, and because they contain so many memories. They’re also a testament to not always throwing stuff away and getting the latest and greatest gear. You can revive gear, keep it going longer than you think. It’s important to not keep consuming blindly.

Notable Achievements

• First ascent of the Shark’s Fin on Mount Meru with teammates Jimmy Chin and Conrad Anker

• Part of youngest team to ever send the northwest face of Half Dome and the Nose of El Capitan in Yosemite

• First enchainment of the Tooth Traverse in Ruth Gorge, Alaska

• First ascent of the southwest Cat Ear spire in the Himalayas

Lou Whittaker

First iteration of the New Balance Rainier boot

The New Balance Rainier boot came to be because of an ulcerated toe. It was 1975. We were sleeping above twenty thousand feet on K2, and I was in these rigid, eight-pound leather boots. The socks and boots pressed my toes together, cutting off circulation. I kept getting this discomfort in my foot, and I wasn’t sure what it was — maybe frostbite. I took my socks off and saw little holes in the sides of my toes. The doctor at base camp said over the radio that I might lose my toes, maybe even my whole foot. I needed to get air to my feet. So I descended the mountain in lightweight tennis shoes. I fell down constantly. It was sixty miles on the Baltoro glacier, and then another forty miles to Skardu in Pakistan.

A few months after I returned from K2, I approached New Balance and proposed a new kind of shoe — something lightweight, like the stuff they were already making, but with heavy lugs on the bottom.

By the time I was back on Everest in ‘82 — the first attempt of the North Wall on the China side — we were outfitted with a great lightweight boot that increased our ability to move high on the mountain, up to about twenty-one thousand feet. From then on, that was the approach shoe on all of my Himalayan trips, as well as an all-purpose boot. On peaks like Kilimanjaro, we wore them all the way to the summit. And soon I began seeing the shoes all over. It gave climbers a lightweight shoe that made approaching, and sometimes summiting, easier than ever before.