Military packs and load carriage have come a long way since the one-strap haversacks of the Civil War allowed a soldier to lug rations and personal possessions onto the battlefield. These early carry solutions involved linen and canvas bags designed for over-the-shoulder carry, gradually morphing into a more complex arrangement of flaps and straps in the World Wars — and leading to the polymer frame, Cordura fabric workhorses in action today.

Through well over a century of innovation, development and patents, two constants endure. First, military packs have borrowed heavily from civilian design elements through the rucksack and aluminum grade frames. Second, civilian pack options for hunting, everyday carry and urban lifestyle pursuits have expanded greatly through the influence of military load-bearing technology like waist belt and MOLLE webbing.

These touch points are often subtle or hidden, lost in the corner of a Wikipedia article or an obscure military journal. However, a closer look at the intersection of civilian and military design efforts reveals four significant moments, bringing us to both the most modern battlefield packs — and the bags kids are rocking as they roll up to the skatepark. As a veteran and current Foreign Service Officer who has researched this history extensively, here’s what I’ve seen.

1. It all started with a canvas knapsack.

Union soldiers began the Civil War with a knapsack of canvas — painted black in an attempt to add water resistance — which they wore on their back via two shoulder straps. The ungainly trunk held clothing and tentage, while a considerably smaller haversack constructed of painted canvas and a cloth lining carried the meager rations of the era, a few personal items and additional ammunition not otherwise worn on a cartridge belt.

Civil War Trunk

This format continued into the twentieth century with only minor modifications, until the U.S. Army Infantry Equipment Board met at the military equipment manufacturing center of Rock Island Arsenal in 1909 and conducted a review of the equipment a soldier was required to carry into battle. By 1910, a new set of specifications was agreed upon that took the U.S. into the Great War and the slaughterhouse of trench warfare, barbed wire and gas attacks.

The olive drab canvas haversack that resulted from these standards allowed for an entrenching tool, mess kit with cutlery, blanket, clothing and tentage to be carried within the folds of the materials. An update to this arrangement was developed in 1928 but would not see production until America’s entry into World War II. Even with this update, these haversacks did not function like a modern backpack and were not favored by the troops. They were essentially heavy canvas burritos the soldiers wrapped around their gear and clipped into web belts.

The World War II Haversack

The military continued on the path of development and created two functional load carrying items, which possessed the sort of dimensions and form we might see in a modern backpack. One was the Bag, Canvas, Field, M1936 (yes, the military has this way of being excessively descriptive), an update to a previous bag initially issued to mounted troops and officers. At approximately 10 liters, it eventually saw widespread distribution to mechanized and airborne troops, and became prized for its modest yet functional organization and ease of carry via a set of suspenders or single strap.

2. The good ol’ canvas pack gets an external frame upgrade.

The first noticeable moment of civilian influence on military design came in the form of the 1941 rucksack. Constructed of duck canvas over a rattan or thick gauge steel wire frame and designed for troops who specialized in mountain warfare, this rucksack consisted of a large main pouch with flap and three external pockets. It has obvious Nordic DNA from Ole F. Bergan’s 1910 invention throughout the bag, frame and shoulder straps, and was certainly not a spontaneous design emanating from the mind of an Army Quartermaster (the guy responsible for issuing equipment).

1941 Mountain Rucksack (courtesy of JW Hale)

The War Department asked the National Ski Association to evaluate the 1941 rucksack, and its Winter Equipment Committee offered 12 recommendations, resulting in a tubular steel frame, a new method of attaching shoulder straps to the rucksack directly and small yet functional improvements which were incorporated into newer versions. The frame and “belly band” waist strap aimed to minimize sway under load, and the entire system marked a dramatic improvement over the ungainly haversack systems provided to the average infantryman.

The U.S. military continued to use external frame packs through the Korean and Vietnam Wars, transitioning the pack material from canvas to nylon — an attempt to minimize the retention of water and resultant dry rot — and shifting the frame to tubular aluminum. It is during this period we see the second touch point between the two dimensions of packs.

Dick and Nena Kelty would revolutionize the civilian hiking world during this era with a home-built pack created in 1952. Their design utilized aircraft-grade aluminum for the frame, surplus parachute fabric for the bag and a hip belt and padded shoulder straps composed of other materials left over from WWII.

Packs would continue to evolve over the next 60 years at a blistering pace, finding use atop Mount Everest and other dizzying elevations as they took on taller, narrower alpine profiles. Military packs of that era culminated with the iconic All-Purpose, Lightweight, Individual, Combat Equipment (ALICE) Field Pack adopted in 1973.

The external frame design retained many elements of the previous generation of rucksacks and remains what many consider the gold standard of combat packs. It weathered on through Operations Urgent Fury (1983 Grenada), Just Cause (1989 Panama), Desert Storm (1991 liberation of Kuwait) and well into the late 1990s. I would deploy with an ALICE pack into Mogadishu, Somalia in 1994 and employed the design until I joined my first light armored reconnaissance (LAR) unit in 2002.

GIs with ALICE packs

While the hiking and mountaineering market continued to move into ultra-light fabrics and frame materials, the military mostly meandered along with its own specifications for equipment, focusing on durability and functionality at the expense of motility. Sporadic attempts to replace ALICE packs resulted in numerous experimentation periods and limited fielding of several internal frame packs like the 420 denier nylon cloth LOCO and the camouflaged CPF-90, created by backpacking industry leader Lowe Alpine Systems.

3. Civilian packs inspire massive military upgrades

By the ’90s, we were beginning to wave goodbye to the days of packs designed by Army civilians and engineers and mass-produced by contract vendors. Instead, the military began establishing performance requirements before seeking proposal specimens from the industry for test, evaluation and selection. This third intersection of civilian and military pack design was an exciting time for the troops who got the chance to use these packs.

However, they were never fully integrated into use with general purpose forces due to their height and the resulting difficulty of use with helmets and body armor. Although these packs excelled at holding a lot of gear, a universal combat pack replacement for ALICE would not arrive until the late ’90s.

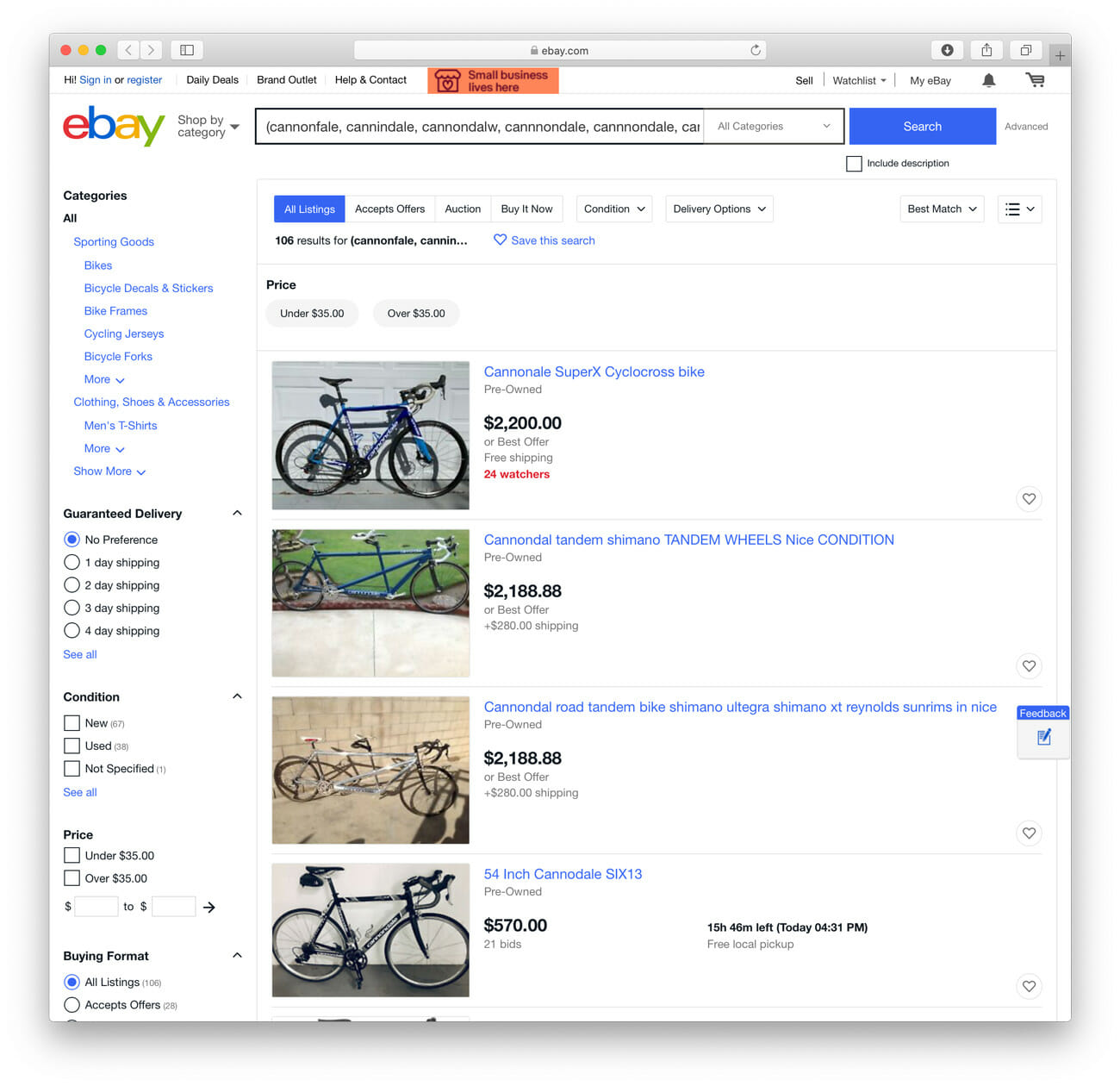

When the United States Army’s Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center patented a grid of one-inch webbing, attached to a base fabric at one-inch intervals, it forever changed the way soldiers carry their equipment, ammunition and provisions to war. This grid, labeled the Pouch Attachment Ladder System (PALS), became the cornerstone of the Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment (MOLLE) system introduced in 1997. PALS allows the user to attach a variety of pouches to base items such as a pack, body armor or an ammunition vest via a strap system laced into the PALS grid. Over time, the term PALS has fallen out of favor and most folks simply refer to the webbing as MOLLE.

Pack with MOLLE webbing, courtesy of Pu Koh

Post 9/11, the Army and Marine Corps began to field suites of MOLLE equipment to service members headed to combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. The system’s top-loading rucksack was covered with webbing and could be quickly reconfigured to mission requirements, but the molded polymer frames frequently broke under normal combat conditions and the zippers were easily fouled by debris. The LAR company that I commanded during the 2003 invasion of Iraq experienced a 40 percent rate of frame failure. We essentially had to go to war with a pack that the Corps was already working to replace because of its flaws.

The Marine Corps ventured away from following the Army’s lead in field equipment procurement and asked the industry to design a new suite to replace MOLLE in 2002. Arc’teryx designed an alpine-style, top-loading pack that supported the load through an internal frame of aluminum stays and load stabilizers. It won the competition against a Gregory Mountain Industries submission and was mass-produced by Propper International as the main component of the Improved Load Bearing Equipment (ILBE) system.

I would return in Iraq in 2008 with an ILBE and then to Afghanistan in 2010 — and could appreciate the fulfillment of the various performance specifications outlined by the Marine Corps. It was heavier than an ALICE pack, but it could accommodate mortar ammunition inside pockets and had side access features. In a classic example of terrible systems integration, Arc’Teryx provided exactly what the design contract called for but the ILBE pack failed to fully integrate with the body armor systems issued to the troops at that time. A new search for a sustainment pack commenced in the late 2000s and resulted in a new collection of load-carrying items designed by Eagle Industries.

While the military struggled for over a decade with issued field gear, a burgeoning industry of MOLLE-compatible products exploded literally overnight as troops sought out tactical load–carrying equipment that performed better than the articles manufactured by lowest bidders. This period saw the rise of 25- to 40-liter “3-day” or “assault” packs from Camelbak, Mystery Ranch and dozens of other companies, along with an assortment of organizer pockets, general purpose pouches and other accessories which could be used during combat operations. I would deploy to Iraq and Afghanistan with a privately-purchased, Lightfighter Tactical, Inc. pack, because it simply performed better than my Marine Corps-issued patrol pack at that time.

The author’s own Lightfighter pack

4. MOLLE becomes the standard in the military — and the design spreads into our everyday bags.

Current options are literally endless, and MOLLE compatibility has even seeped into a range of military-inspired backpacks, messenger satchels and sling packs which were never intended to be taken into battle. This phase of pack design represents the fourth and final touch point along a civilian and military through-line that grows more blurred over time.

I went looking for the moment of this design spark in late 2016. My search began at a tactical discussion forum, gathering bits and pieces from a thread about a remarkable backpack that had debuted several years earlier. A member of the forum spoke of a friend who had been on the pack’s design team, and the search eventually shifted to Facebook, where I met a Nike designer who worked on a different design team from 2003 to 2016 but knew the people involved in the pack’s release in 2007. He, in turn, referred me to soft goods designer Thomas Bell, as well as the director of the company’s archives at Nike DNA.

When I communicated with Bell, he spoke about his design philosophy and details of the Nike skateboard (SB) pack and its shoe, hat and camera accessory cases that were initially offered at product launch. He found inspiration in the “form-follows-function design principles of military products,” and the original SB pack certainly raised eyebrows in the tactical arena when it first arrived. It remains a hip, urban realm pack and it is amusing to watch video reviews. Across some 30 minutes of reviews from multiple vloggers, none of them even mention the PALS grid or the possibility of expanding the pack’s carry capacity with a MOLLE-compatible pouch or two.

Nike SB’s military-inspired pack

For the unfamiliar observer, the true capability of the PALS webbing on Nike SB packs has faded from memory, becoming nothing more than a decorative element on this trailblazing backpack designed to hold a laptop, miscellaneous tech gear, clothing and a skateboard.

As a design element, a swath of PALS webbing on a lifestyle pack has actually become commonplace, with Greenroom136, Timbuk2, Equilibrium USG and several other manufacturers offering a range of packs that could mate with a MOLLE-compatible accessory if the owner so desired. You could argue that they are not crossover packs, as soldiers are not likely to dash into a firefight with Nike packs on their back. But I have no doubt that the civilian and military sectors will continue to borrow load-carry innovations from each other for the next 150 years.