From Issue Six of Gear Patrol Magazine Issue Ten is available now.

To really put a motorcycle through the wringer, it has to be pushed to the limits of its purpose in the harshest way. Sport bikes are flogged on the track in 100-degree heat, dirt bikes are thrown through the woods and over jumps for hours on end, and cruisers endure endless miles on the world’s greatest highways. But how to put a strain on a scrambler, a bike made both for tame roads in town and for wily dirt trails out in the boondocks? To find out, we took a pair of scramblers 2,678 miles up through the Canadian Rockies and into Alaska to show them North America’s most infamous stretch of road: the Denali Highway.

Scramblers have recently swelled in popularity, but they’re nothing new. The scrambler rose to prominence in the rebellious ‘60s and ‘70s; it was created at a time when motorcyclists stripped down standard sport bikes to their bare essentials, kitting them out with bigger suspensions and knobbier tires to make them competent in the dirt and in off-road racing. But the concept of a scrambler wasn’t all that groundbreaking in the ‘60s, either.

The purpose of the first motorcycles was to render the bicycle obsolete and allow people to travel farther and cover more miles in a day on two wheels than ever before. In the late 1800s, they were just bicycles with miniature engines that supplemented pedal power; they quickly evolved into the utilitarian two-wheeled transportation the world knows today. The evolution wasn’t necessarily driven by a search for speed, but by an insatiable appetite for freedom and exploration, a basic sense of adventure. Before smooth, direct, arterial highways and intricate webs of paved infrastructure spread through the country in the 1920s and ‘30s, connecting all our major cities, there was dirt, mud, gravel, sand and stone. Motorcycles had to be able to tackle it all, and tackle it well.

Having a motorcycle that was capable on both paved streets in town and on dirt roads in the country wasn’t a stylistic choice; it was a necessity. Every time you hopped in the saddle, hitting both types of terrain was a near certainty. As paved roads became more common and the modern highway system introduced more civility to the average motorcycle ride, the mandatory go-everywhere features faded from factory-built road bikes. Sport bikes, cruisers, choppers, they’re all bound to paved roads with stiff suspensions and slicker tires. Scramblers, then, were created as a way to gain back the freedom of comfortably riding any road, paved or not.

Over the decades, scramblers became more focused and purpose-built, eventually morphing into modern dirtbikes, dual sports and hardcore adventure bikes. Somewhere along the way, they became more concerned with function than form and, in the process, lost the interest of casual riders.

The bikes in question: Ducati’s Scrambler Desert Sled ($11,395) and Triumph’s Street Scrambler ($10,800)

The current crop of scramblers is gaining favor with the masses because they bring back that go-anywhere freedom with old-school style. But most importantly, they’re compact, approachable machines that both new riders and two-wheel veterans can get excited about. Like their forebears, they balance on-road worthiness with off-road prowess.

The Ducati Scrambler Desert Sled and Triumph Scrambler are the headlining stars of the modern scrambler craze, and I wanted to know if both were truly worthy of carrying the torch. Could they hack it outside city limits? If and when these bikes saw dirt, would they falter and fail or take it in stride? Are they just fashion statements? Can they hold their own in a veritable theater of two-wheeled warfare — long highways, sweeping canyon stretches, suspension-shattering dirt roads, sand traps — and survive what would be a torture test for even the most refined and focused adventure bikes?

North of Seattle, up through British Columbia and the Yukon Territory, over into Alaska and down to Anchorage: the northwest passage of North America is a modern-day adventure-vehicle playground of high deserts, mountains, canyons, rivers and glaciers. But the terrain is as majestic as it is life-threateningly treacherous. It’s mostly paved, but dirt, gravel and unfinished, primitive highway make cameo appearances to keep you on your toes. The farther north you venture, the less common average family sedans become. Lifted Jeeps and Toyota 4Runners decked out with high-lift jacks, full-cage roof racks and light bars become the norm, the suggested mode of transport. For two-wheelers here, the recommended bare minimum would be purpose-built, precision all-terrain instruments like the BMW R 1200 GS or 1290 KTM Super Adventure — top-of-the-line adventure bikes with powerhouse engines, active suspension, power outlets and heated grips. Paved roads or not, it’s no place to go underprepared and let Mother Nature catch you with your pants down. Despite all that, we chose to ride out of Seattle astride the fairly analog Ducati Scrambler Desert Sled and Triumph Scrambler, like bringing pocket knives to a trench war.

Day 1

False start. A passport packed in a forgotten bag sat idle in LA. The plan had been to fly into Seattle Friday morning, pick up the Ducati and Triumph and our Mercedes Sprinter 4×4 chase van, then head out of town to Vancouver for the night. Gregor, a friend and experienced off-road racer excited to check off riding in all 50 states with the trip to Alaska, would pilot the Ducati. I called dibs on the Triumph while Sung, our tenacious photographer who, we learned, has a slight aversion to sleeping on the ground, looked forward to calling the Sprinter home for the next seven days. The first day was designed to be less intense, so Gregor and I could get used to the unfamiliar bikes with easygoing city and highway miles. Needless to say, that plan, for the most part, was now scrapped.

After a few four-letter words and a couple frantic phone calls, the passport was arranged to leave LAX the next morning on a Delta flight and get to us by 9:30 a.m., Saturday. We had no choice but to book a room at an airport hotel and hit the road as soon as the passport arrived.

Not the most auspicious start to a journey of this magnitude.

Day 2

10:32 a.m., passports in hand, blue skies above, we pointed our convoy north and set out on what would be the longest leg of the entire week. To make up for the lost day, we decided to circumnavigate Vancouver completely, combining two days’ worth of riding in order to make it to Prince George on schedule. The easygoing miles we planned for the first day had morphed into an endurance break-in test.

Right away, I decided that a wind screen, even a small something to break up the wind, would have been luxurious. Buffeting at 65 mph isn’t just annoying; after too long, fighting the choppy air is physically exhausting. Our mileage hadn’t even hit triple digits yet and we already could feel this ride trying to wear us down.

As soon as we crossed the U.S.–Canadian border, we hopped on the Trans-Canada Highway and made our way around the bottom of British Columbia’s western mountain range, up through Wells Gray Provincial Park and into what looked like the heart of the Canadian wilderness. In reality, we’d only just dipped our toes into the deep end of a pool, and we couldn’t see the bottom. Emerald waves of mountains gave way to sun-baked high desert, ravines and long, meandering rivers contoured by an endless strip of train tracks straight out of a spaghetti western. Motorcycle paradise. As the light faded, though, so did the novelty of the first day’s ride, and with it, the warm Canadian welcome. Darkness ushered in a bitter cold. At 8:53 p.m., a debate raged inside my helmet: Do I signal for us to pull over so I can pee, or would holding it actually keep me a little bit warmer? Tough call. It’s 10:48 p.m. when we arrive in Prince George — finally

Day 3

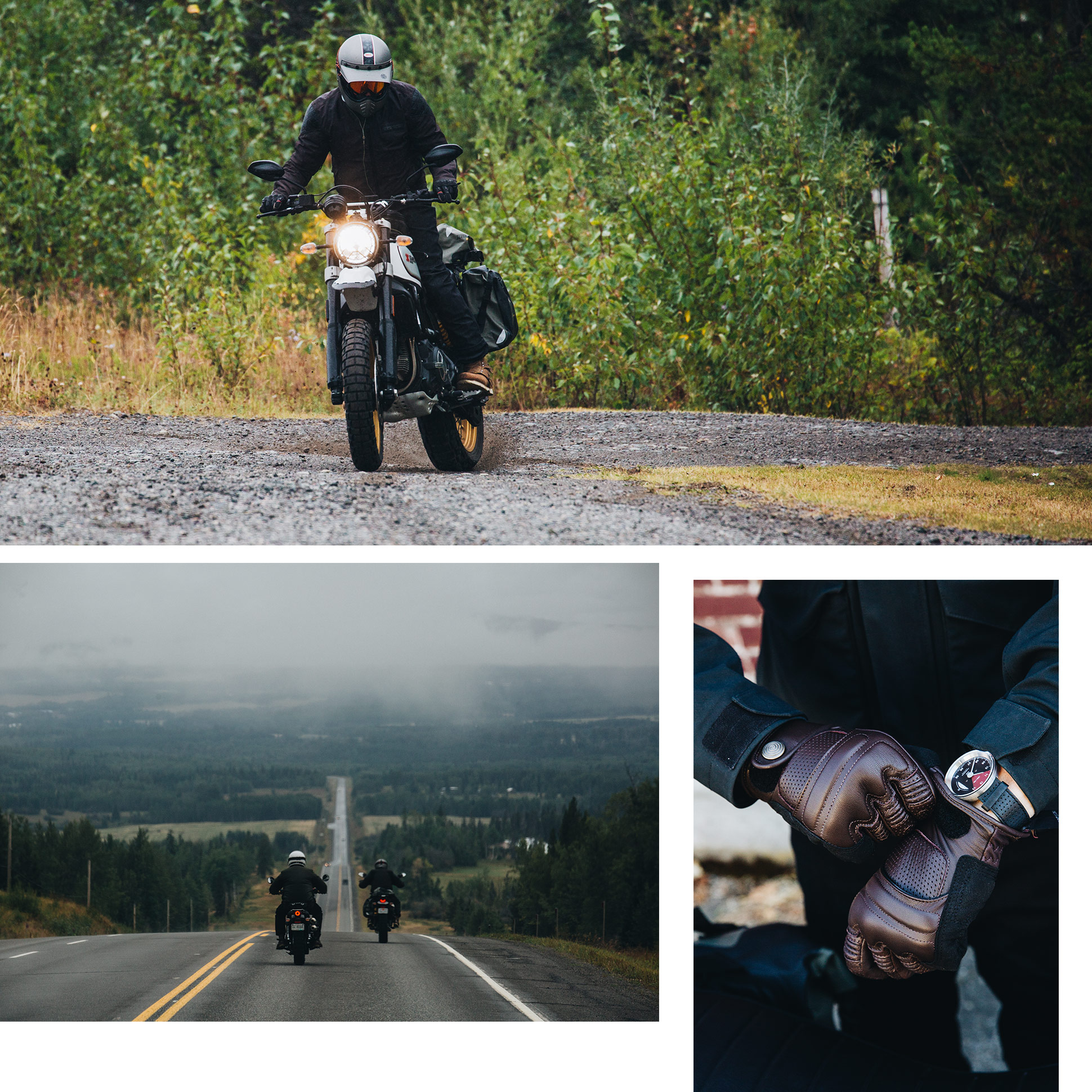

Above: Bell Moto III ($359), Icon 1000 Squalborn Jacket ($300), Rev’it Jeans Memphis H2O ($320), Icon 1000 Elsinore Boots ($245)

Below Right: Oscar Robinson Gloves ($90), Autodromo Veloce ($425)

Overcast skies and cool crisp air greeted us as we saddled up for day two, this time appropriately layered up. Prince George would be the last populous city we’d see for two days. We set out for our waypoint — Meziadin Junction, just under 400 miles to the northwest — which we thought would be our last stop for the day.

Almost immediately, we waded into a vast rolling sea of towering evergreens like surfers getting towed out into big wave swells. Unfiltered aromas of pure pine and maple, frequently accompanied by the scent of smoke from a campfire or a logging compound, flooded my nose at 65 mph — the exact olfactory experience air fresheners aim for but never capture.

Turning north onto Highway 37, we were now racing the sun to the horizon, Otter Mountain looming at the finish line. Gregor was leading at a brisk pace, carving up what felt like Canada’s Nürburgring. Neither of us were interested in getting a second helping of cold Canadian night riding, so there was an unspoken agreement to keep the speed up. About two hours and 90 miles later, the Ducati started to sputter and Gregor signaled to pull over. Out of gas. Judging by my gauges, the Triumph wouldn’t have made it much farther. Nearly 30 miles from Meziadin Junction, the jerry cans full of spare fuel proved to be a wise investment.

Meziadin Junction consists of a fuel pump, a convenience store, a few rooms all taken up by construction workers and a café that closed minutes before we got there — that’s it. No town. No other lodging. I swore this was where our Airbnb was supposed to be. The store clerk explained that the closest town was Stewart, at the end of Highway 37A, about 38 miles away, which a double-check of the reservation confirmed. I could see the enthusiasm physically fall off of Gregor’s face: we suddenly had another hour to go. Soft twilight gave way to pitch black. Worst of all, we’d have to split Otter Mountain and Mount Johnson — prime real estate for avalanches and rockslides. We were riding through a narrow chasm with only our headlights illuminating a relatively small patch of road in front of us. The inky-black sky was nearly indiscernible from the titanic terra looming in the darkness all around us — riding into the ominous, massive void induced a strange claustrophobia.

In Stewart, relieved to finally be off the road (again), we vowed to get early starts from here on out and avoid stints at night. Riding through a vast wilderness in blinding darkness is terrifying.

Day 4

We were forced to backtrack toward Meziadin Junction since Stewart is basically a dead end on Route 37A. Intense morning sun flooded the canyon road, confirming our suspicions of just how close those rock faces were. Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue skyscrapers are less imposing. Beyond the canyon, lush green mountain ranges capped with residual year-round snow sat on pedestals of golden fields flush with wild flowers.

We fueled up both our bikes and bodies in Meziadin Junction, where we ordered Loggers Breakfasts at the café: three fried eggs, sausage, ham, two pancakes, hash browns and a cup of coffee. Yeah, that should hold us over.

Route 37 took us about 400 miles to Watson Lake on nonstop sweeping asphalt that scythed its way through vast swells of dense woodland. After nearly two hours and 130 miles of banked turns at 75 mph, the Triumph started to sputter. My turn to run out of gas. We drained the jerry cans. Fifty more miles down the road, we came to a fuel stop, refilled the reserve cans, grabbed food to cook at that night’s campsite and set off again. The next four hours and 260 majestic miles of northern British Columbia were punctuated by two more roadside fill-ups.

We made it to camp with plenty of daylight to spare (for once). Gregor started a fire, boiled water for asparagus and threw steaks and potatoes on the coals. A toast with Canadian whisky. A meal worthy of the day.

Above Right: Icon 1000 Squalborn Jacket ($300)

Below Right: Aether Range Pant ($395), Icon 1000 Elsinore Boots ($245)

Day 5

To follow up our two 400-plus-mile days and the first 500-plus-mile day, we cut day five short and set up camp just outside of the 25,000-resident-strong city of Whitehorse. At this point our sense of time and distance was warped, but in a good way; we’d adapted our minds to the long-haul ride and stopped thinking about each leg in terms of miles or hours. Instead, we measured in tanks of gas. Only 278 miles to Whitehorse? We’ll only have to fill up on the side of the road once. Brilliant.

When you’re in the saddle for 130 miles at a time, two things are mandatory to maintain sanity. One: you have to like yourself, because you’re the only person you’re going to be spending quality time with for hours at a time. (A good singing voice is a plus.) Two: you have to like the bike you’re on. It might seem obvious, but if the bike is uncomfortable, it becomes an open-air torture chamber — getting back on every morning for 500 straight miles will have you questioning all your life choices leading up to that moment. It’s a solitary experience, but on a bike as smooth on the road as the Triumph, and with Yukon scenery to stare at all day, a ride like this is downright meditative.

Day 6

Gregor (Left): Bell Moto III $359, Icon 1000 Squalborn ($300), Rev’it! Jeans Memphis H2O ($320), Icon 1000 Elsinore Boots ($245), Ducati Urban Enduro Waterproof Rear Bag ($169)

Bryan (Right):

Helmet: Bell Moto III Helmet ($359), Von Zipper Porkchop MX Moto Goggles ($75), Ashley Watson Eversholt Jacket ($704)

Almost 1,800 miles in and we hadn’t seen much dirt. But just past Mount Cairnes, the Alaska Highway sweeps along the shore of Kluane Lake. Fog had settled on the lake’s surface, rounded mountains framed the cyan sky and Sung wanted a photo. I spotted a gravel path just off the side of the road. No need to ask me twice.

The narrow two-track led to the beach, which became the highlight of the day. Our scramblers had proven themselves worthy of the road, but sand and pea gravel can make or break a bike. Gregor’s Desert Sled had an advantage on the beach; it’s lighter, has a little bit more suspension travel and more ground clearance. Still, he was putting in hard work to keep from being devoured by the powdery sand. Armed with knobbier tires, but weighed down by a little extra bulk and lower ground clearance, the Triumph was able to keep up, but it did struggle. When I kept my speed up, I positively floated across the beach. Then it came time to slow down and turn back, and I beached it. Skid plate flat on the sand, rear tire roosting and digging, the beach was swallowing the bike whole. After a few side-to-side rocks and a steady throttle, I began inching forward, then free, back buzzing the shoreline like a dog off the leash. Exactly what these bikes were built for.

Back on the road, as if the beach wasn’t enough, the last few miles of the Alaska Highway leading up to the Alaskan border were largely unpaved. For the better part of 30 miles it was open, gravel-covered highway: scrambler country.

Alaska Highway kilometer marker 1,818. The Triumph coughs, sputters. We pulled over in front of Discovery Yukon Lodging, filled up our bikes, then went inside and asked the sweet-little-old-lady innkeeper for coffee, which she said they don’t usually do. But she put on a pot for us anyway and brought out fresh-made apple walnut cake topped with homemade frosting. Lifesaver.

We ended the day across the Alaskan border at our cabin in Tok. The second longest day, but only by a few miles.

Day 7

Today was the crown jewel of the entire ride. Alaska Route 8, the Denali Highway: a 135-mile stretch of road connecting Paxson to Cantwell, only 24 of which are paved. A hundred and eleven miles of dusty gravel, wheel-hungry ruts, and bone-shattering washboarding. On the Denali Highway, when the pavement stops, so does the bullshit.

This is all-out adventure-bike territory. It calls for active suspension, adjustable ride height, multilevel traction control and ride mode selectors. We could’ve taken a BMW R 1200 GS or a KTM Super Adventure, which have all the aforementioned tech, to make our lives easier. We could have hopped in the warm, high-riding van with Sung. Instead, on the visceral scramblers, we were involved, working for it. There was nothing filtering out the raw, unadulterated experience of one of the toughest roads Alaska has on offer. The bikes were at home. For 111 miles, the Ducati and Triumph reached scrambler nirvana.

Day 8

Our last day. The final 200 miles. It’s 10 a.m. as we pack up camp under bright blue skies. The cool, crisp air marinating Denali National Park lulls us into a false sense of comfort with Alaska. Out on the road and barreling down Route 3, it isn’t long before we hit rain. We had come across a few light showers the previous couple of days, but this was the first real storm. Alaska isn’t going down without a fight.

The temperature drops. The bike’s thermometer reads 42 degrees Fahrenheit; seems optimistic. With no windshield to hide behind, rain sticks to the dirt on the goggles. Spray from traffic is killing visibility. There’s a cold creep of freezing rain working its way through my jacket and pants — soon I’m completely saturated. Is the road surface uneven, or am I actually shivering? Hands are numb, stiff. I’m definitely shivering. Another five miles and maybe we’ll be past it. Okay, two more miles. Turn signal, on — we’ll wait it out, warm up and dry off in the Sprinter instead. First things first. Heat on high, heated seats on max. Defrost.

Gregor checks the weather for a sitrep. There’s good news and bad news. Good news is, the rain stops… around 8 p.m.. The bad news is, that’s when it starts snowing.

There’s talk of putting the bikes in the Sprinter and hauling them into Anchorage. I push back. We didn’t come 2,400 miles on these bikes to cross the finish line in the support van. Sung is understandably worried for our safety and Gregor looks miserable. Gregor does the math: at about 40 degrees, traveling at 65 mph creates a 25-degree wind chill. Hypothermia is a tough argument to rebut.

Bikes in the back of Sprinter, onward to Anchorage. The van is silent aside from the barrage of wind and water against the windshield. The lead weight of defeat is sitting in my gut, growing with each passing mile. Alaska was winning the fight in the final hour.

Ten miles later, my eyes are welded to the horizon as the sky brightens and the rain eases up. Gregor checks the weather again. We’re actually outside the radius of where any weather radar stations can see.

Thirty miles still farther, a break in the clouds. We’re in between two weather cells: a chink in Alaska’s armor, a window of opportunity.

I’ll be damned if I’m going to ride into Anchorage on anything other than that Triumph. I order Sung to pull over — we’re getting the bikes back on the road.

In Trappers Creek, we unload the bikes and throw on some extra gear in case we hit the storm again. Thicker gloves and an extra down jacket under my now warm, toasty, dry motorcycle jacket for me, and a full all-weather suit for Gregor. Fuel for the bikes, filled to the brim.

We’ll have to haul ass if to avoid being caught in that deluge a second time.

Full throttle.

One eye on the road, one eye on the storm cell to our left. Like trying to race a train to the crossing.

Every kink in the highway fiendishly points us ever so slightly toward the wall of water in the distance. Alaska, it would seem, isn’t done with us yet.

Pelting rain turns to a shower, turns to a downpour. We’re back in it, and passing cars and trucks is becoming a game of roulette. Spray from 18-wheelers puts us in a grayout; we’re basically riding blind. We have no choice. Alongside the trucks, all we can do is tuck our heads and lean a shoulder into it.

Soaked.

Seventy-five miles to Anchorage.

Fifty miles to Anchorage.

The sky brightens, and I don’t trust it. But, finally, Alaska relents.

I don’t see any bright, neon “Welcome to Anchorage” sign, no ticker tape parade to let us know we made it. But holy hell, the relief. The overwhelming sense of victory lays on us like a wet wool blanket. Lazily clicking down through the gears, getting off the main highway and into town, we’ve clearly crossed our marathon’s finish line. We made it.

Epilogue

Looking at a 2,600-mile route on a map versus riding every inch of it on a scrambler is like flying over an ocean versus crossing it in a sailboat. You can get a sense of scale, but it’s not until you’re experiencing each bump, rut and crack, looking 30 or 40 miles to the horizon, that you can really appreciate the vastness, the grandeur.

We could have done this trip on terra-dominating adventure bikes with all the electronic assists to make it easier, more comfortable. We could have just taken a fully decked-out Land Rover. We would have seen just as much — and stayed dry. But on the scramblers, on the paved roads, on the beach, in the dirt, through the mountains, it was equal measure rider and motorcycle, the essence of two-wheeled adventure. The reason why we started riding motorcycles in the first place.