There are many reasons to love motorcycles, but two specific ones brought me into the fold of licensed riders: the sound and the style of classic bikes.

I started out riding new motorcycles with modern safety equipment that were perfect for easing into the world of riding, especially in the distracted driver-packed asphalt hellscape that is Los Angeles. But it didn’t take long for me to desire an even more direct connection with the machine: more noise, more gasoline aroma, a more involved riding experience. What I didn’t desire: the headaches that come with riding a classic, such as (but not limited to) physical and mental discomfort, mechanical failure, a comparative lack of safety, and the increased chances of theft.

Fortunately, there are ways to have your cake and eat it too when it comes to old bikes. Roughchild Moto is a company mission is to minimize the headaches associated with classic BMW motorcycles, while retaining the attractive qualities of those bikes. Or, to put it in their words: “We are dedicated to the passionate study and preservation of the world’s most respected motorcycles, optimizing their aesthetic appeal with a fresh perspective and modern techniques.”

Robert Sabel and his team got Roughchild off the ground in 2012, focusing on careful restoration and thoughtful optimization of the classic BMW “R-Series” motorcycles produced from 1970 to 1995.

“I prefer the client explains what they want to achieve and let us source the donor as although they seem similar,” Sabel said. “All the airheads from 1970-1995 have different qualities; it’s much more efficient to modify the bike with correct core qualities.”

Once a donor is in the door od their downtown Los Angeles facility, it’s up to the client to lay out their ideas. Roughchild Moto prioritizes safety, reliability, and—of course—a high degree of aesthetic appeal in its builds; beyond that, it’s up to the owner to say what the bike will become. All the hardware used on the bikes is top of the line, from Brembo brakes to Motogadget speedometers. All upgrades are up to OEM standards, or improve upon the original high-quality German engineering; while they were stout and impressive machines in their day, the shop does an excellent job bringing them into the modern era without losing the details that made the R-Series bikes so enjoyable in the first place. Roughchild doesn’t cut corners, even if you ask them to.

The first bike of theirs I swung a leg over was a sexy, blacked-out extended-wheelbase 1973 R75/5 that had received a light scrambler treatment. I found it to be quite the stable bike, offering a surprisingly smooth ride on LA’s bumpy highways. There certainly was no lack of go with the damn thing either. The 750cc engine tucked inside a gloss black powder-coated frame had been rebuilt to factory specs, and featured machined heads with new valves, honed cylinders, and new piston rings. Brand-new Mikuni carbs and a reverse cone exhaust setup gave it a soul-stirring sound; the classic boxer thrum you’d expect from a BMW is there, with the noise escalating into a glorious basso profundo racket as the throttle advances. It’s a bike that urges you to go faster—and farther —than you’d expect.

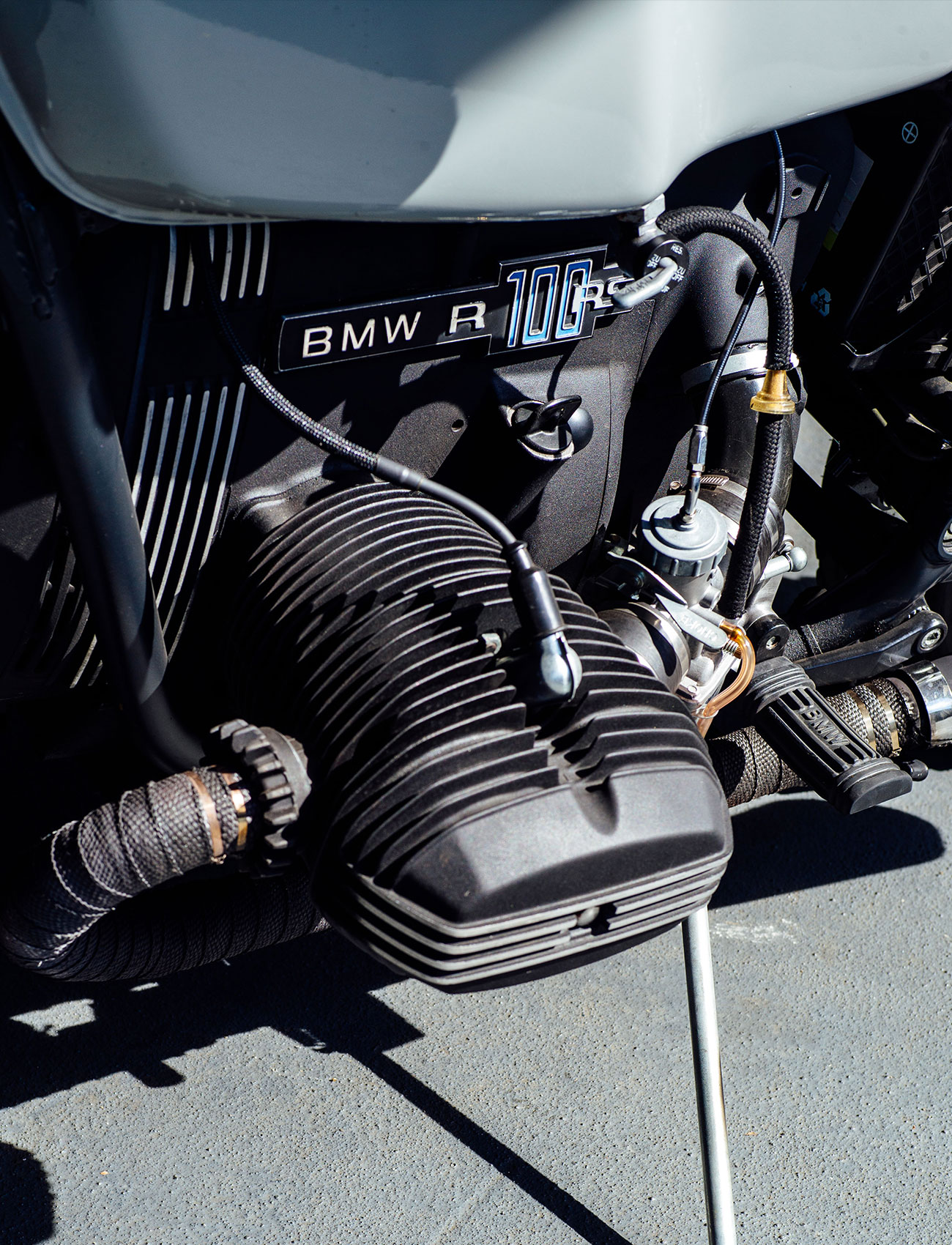

As much as I liked the blacked-out R75/5, the second bike I rode stole my heart. The R100 RS was the high-performance air-cooled machine of my dreams. Producing 70 horsepower in stock form and with reverse cone exhaust setup making an enjoyable racket, this bike offered up a riding experience I’d be hard-pressed to forget.

The Roughchild R100RS pushed me to stay on top of it, methodically tackling curve after curvy road. The lines of communication between me and the bike weren’t as crystal-clear as with othe vehicles; gear changes and throttle use had to be well-planned, or else the bike would wind up doing something very different than I wanted. The machine doesn’t do the bulk of the work for your, like a new bike does; you really have to ride it. It leaves you sore in places you didn’t know you could be sore, but damn, does it feel worth it.

There were other benefits to this beautiful bike, as well. When I parked the R100RS each night, I couldn’t help but stand and stare at the gas tank; it was painted “Fashion Grey,” a Porsche color from the 1950s commonly found on the 356, and, when paired with the brown leather seat, iconic gold Ohlins shocks and shiny silver Brembos, made for an extremely aesthetically-pleasing package. (Not surprisingly, the owner of this particular bike is also into air-cooled Porsches.)

Roughchild’s restorations start at $15,000 for a finished bike (including the donor vehicle) and top out around $20,000, which isn’t bad for a rebuilt and upgraded piece of 20th Century motorcycle magic that happens to come with a 12-month warranty. Quality doesn’t come cheap, especially when it comes to the restoration and improvement of iconic machinery. That being said, there’s a ton of subjective value in these builds; the experience of firing one up and ripping away in first gear is worth the price of admission alone. Add to that the unquestionable visual appeal, and anyone who buys a Roughchild Moto machine likely has a lifetime of satisfaction to look forward to.