Driving through the Swiss Alps feels like a timeless experience insomuch as the scenery seems unchanged from that of, say, 200 years ago — a cotton-like mist of snow covers cozy wooden houses in small villages, obscuring everything farther than 30 feet away from you; white church spires pierce the sky and sheep seem to outnumber their human counterparts. This is the beautiful, isolated environment in which Swiss watchmaking germinated and from which it was subsequently disseminated to the world.

Though Montblanc, a company perhaps most recognizable for its beautiful writing instruments, only began producing watches in 1996, it has certainly come a long, long way in a very short time, diversifying into several different lines (such as the 1858 and Heritage Collections, most recently) and flexing its horological muscle. When it acquired the Minerva manufacture, which has been making watches continuously since 1858, Montblanc inherited a storied history that allowed it to expand into the heritage watch space, crafting new designs that harken back to the golden age of mechanical watchmaking of the last century.

We recently partook in a journey to discover Montblanc’s watchmaking facilities, which are located about 40 minutes from one another in the Jura Mountains.

The Montblanc “snow peak” logo adorns the company’s Le Locle facilities, spread over two buildings high in the mountains about two hours outside Geneva. Montblanc itself was established in 1906 in Germany and is still headquartered in Hamburg (where its pens are produced), though watch production takes place in Switzerland, and leather goods production in Italy.

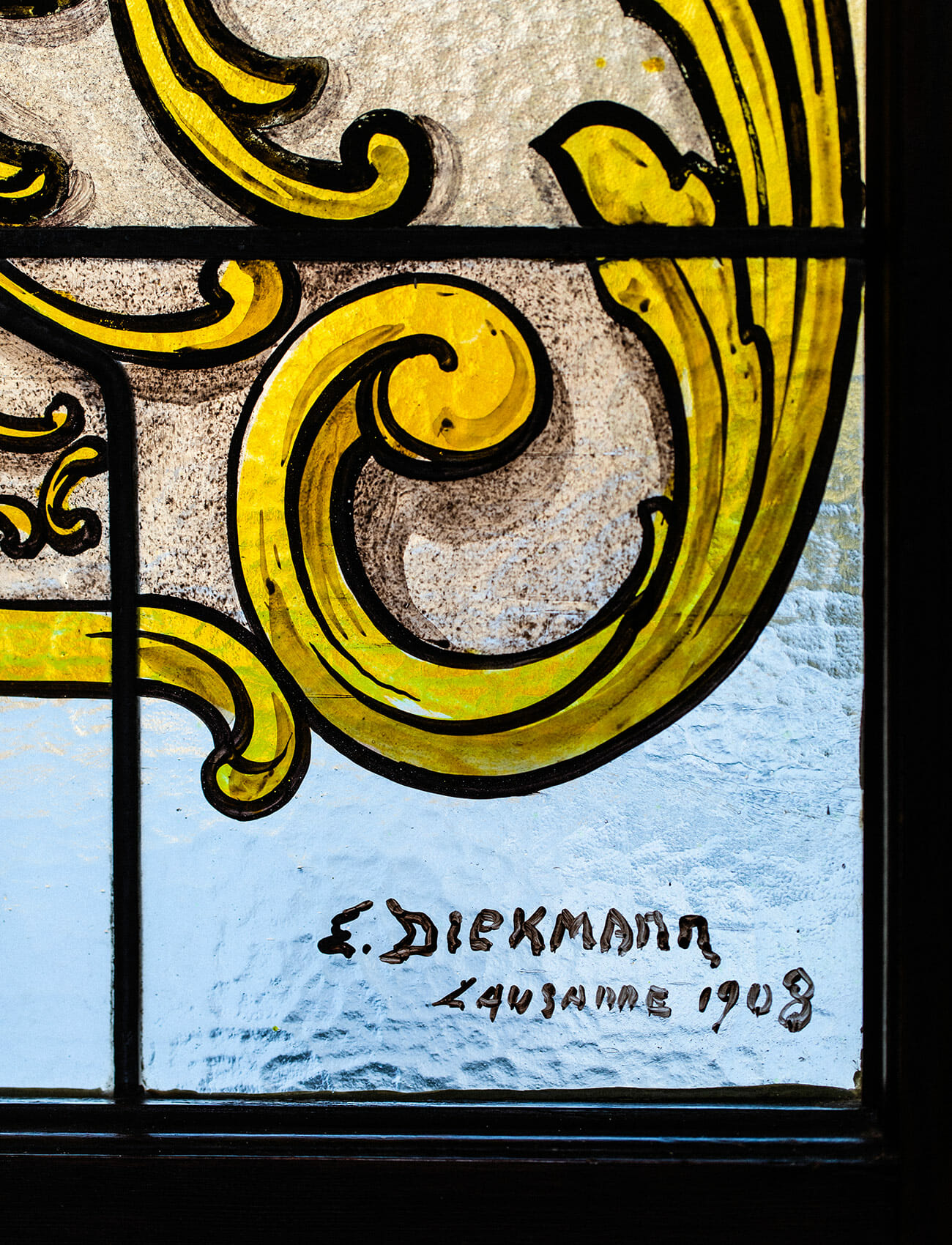

The first of Montblanc’s two building in its Le Locle facility was built as a family home in 1906. Though most of the architectural elements remain intact, the company built a state-of-the-art facility beneath the main building for assembly of the Heritage watch line.

The second building in Le Locle houses design, marketing and development teams for all of Montblancs’s watch lines. There are two project leaders and two constructors on the development team, and it takes an average of one year to develop a new collection. Sometimes an individual design goes through 150+ different iterations before final production.

The device in front of this watchmaker with the different colored handles is used to apply precisely controlled amounts of pressure to watch hands in order to affix them to a watch movement. Each movement requires a different, very specific amount of pressure in order to affix the hands, which is monitored via a computer screen in front of the watchmaker (noticed the USB cord).

Montblanc movements must be assembled and regulated before being disassembled, cleaned and then reassembled. Once this process is over and a given watch is performing satisfactorily, it is sent to the 500 Hours Test, where it is subjected to a battery of physical tests that it must pass before it can be sold.

A tray of Montblanc Bohème Day & Night 30mm watches awaits testing. An electronic machine that holds 10 watches at a time simulates different positions that the watches might be held in and tests the accuracy of the movements in those positions. If a watch passes this test, the process is repeated after 24 hours, and then the timepiece has its power reserve tested. If the positional variation test is not passed, the watch must be readjusted and tested again.

A Montblanc timepiece from the 1858 collection is shipped with a card that will give the owner technical information on its provenance, such as the collection name, type of movement caliber, serial number, case number and more.

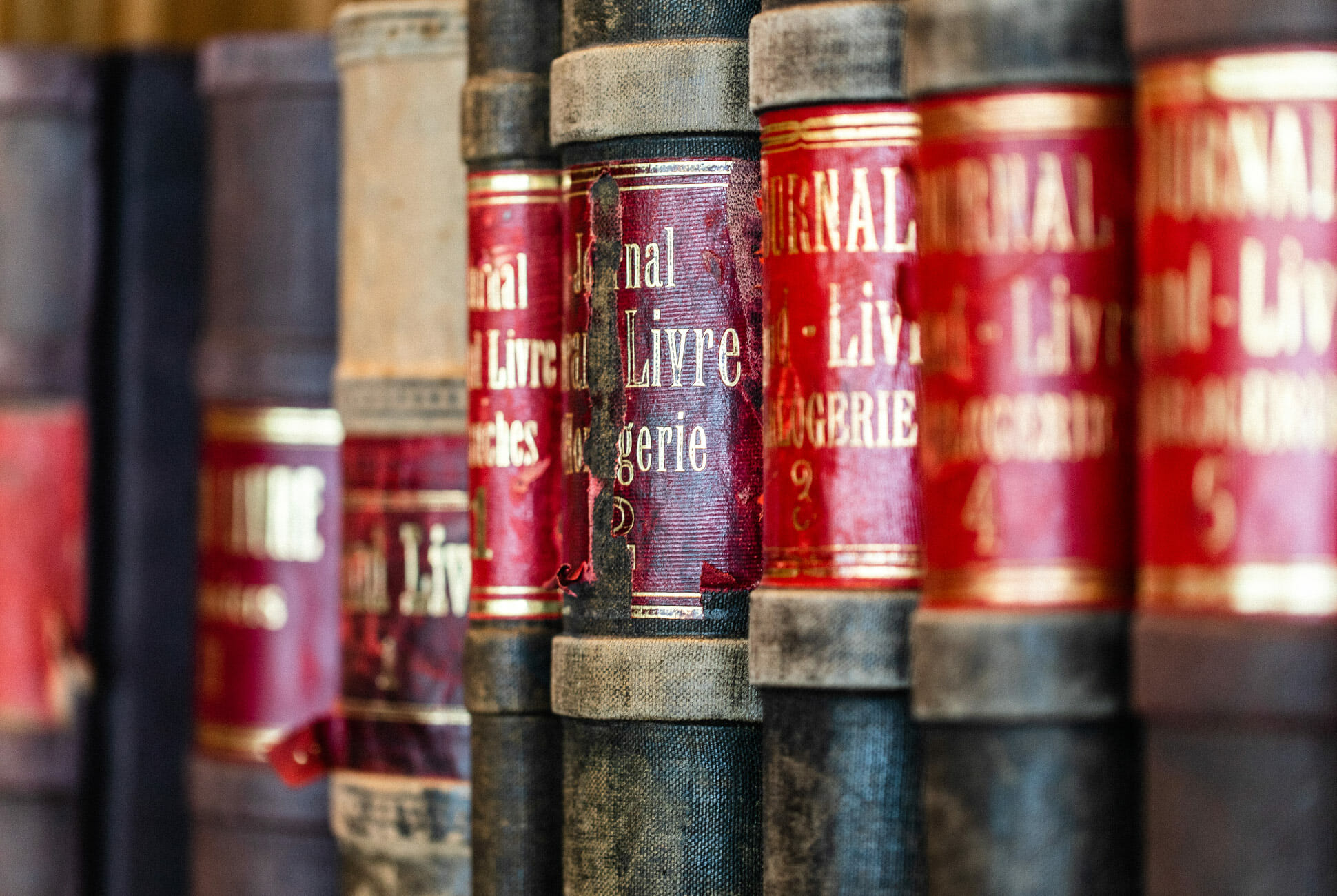

Minerva has been continuously producing watches and movements since 1858, despite a fire in 1973 that destroyed part of the Villeret manufacture. After Montblanc acquired the company, much material documenting the history of the brand was found, some of which is currently on display. These log books are sales ledgers from the early history of the company.

Other items on display in the Villeret manufacture include vintage Minerva tooling, literature, photographs and boxes from Minerva stopwatches. For fans of the brand, this is a virtual treasure trove detailing the history of the manufacture.

Perhaps one of the most informative of the many artifacts from the Minerva manufacture is an enormous set of wooden drawers full of vintage, unused dials and parts, carefully categorized by size and type and often still wrapped in their original paper wrappings. They form gorgeously illustrated history of Minerva’s watchmaking legacy.

A vintage Minerva military-style mono-pusher chronograph with rotating bezel, telemeter scale and radium-coated luminescent numerals. Minerva began manufacturing chronograph movements in 1909 and quickly became famous for their mono-pusher models. These historical references became the basis for the modern 1858 Collection from Montblanc.

After the 1920s, Minerva began supplying stopwatches to professionals, such as those timing races or soldiers in the military. This particular example is calibrated in 1/100ths of a second and features a sub-dial that measures elapsed seconds.

A Montblanc main plate made (which holds the movement components) of German silver with beautiful perlage finishing. Perlage is a finishing technique whose resultant look resembles a pattern of overlapping circles, and is applied at Montblanc by hand using first a metal tool, then using wooden sticks with emory tips.

A watchmaker uses a balance wheel and hair spring suspended under a glass instrument as a reference in order to define the length of a second hair spring (the hair spring controls the rate at which a timepiece runs). She synchronizes the movement of both hair springs visually over a period of 30 seconds in order to ensure that they are beating at the same rate.

A chronograph is assembled and checked, a process that requires on average 2 days of assembly, and up to 8 weeks for the most complicated of chronographs. To give an idea of the degree of finishing involved in these watches, watchmakers must rub components that require mirror finishing together until they not only feel, but also hear no more scratches.

Vintage Minerva objects, such as this movement component box, can still be found throughout the Villeret facilities. The upward-facing arrow is the symbol of the Minerva brand and represents the tip of Minerva’s spear (Minerva is the Latin name for Athena, goddess of wisdom, the arts and warfare).

The view from the penthouse on top of the original Minerva manufacture in Villeret (technically, the first Minerva building from the 1850s was a small green house currently located across the street from this facility, which now serves as the local Protestant minister’s house). Two modern buildings flank the Minerva manufacture in which Montblanc manufactures movements and hands.

Below the mountains viewed in the previous image is the town of Villeret, also visible from the penthouse in the old Minerva facility. The original green Minerva building from the 1850s is just out of frame, but once can get an idea from the image of what a typical charming Swiss town in the Jura Mountains looks like in winter. The relative isolation and many months of cold provided a perfect environment for watchmaking.